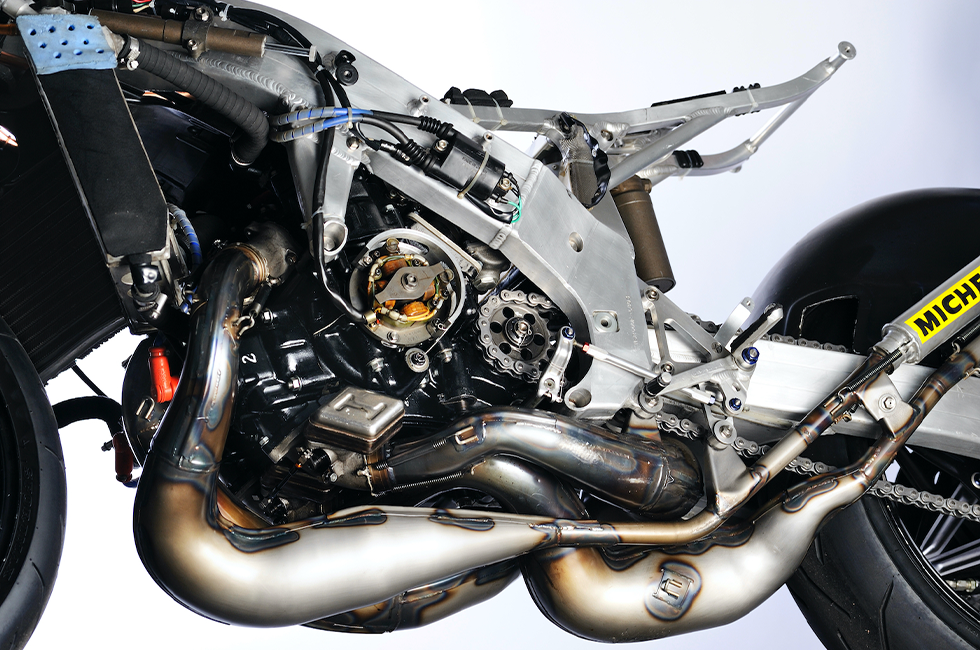

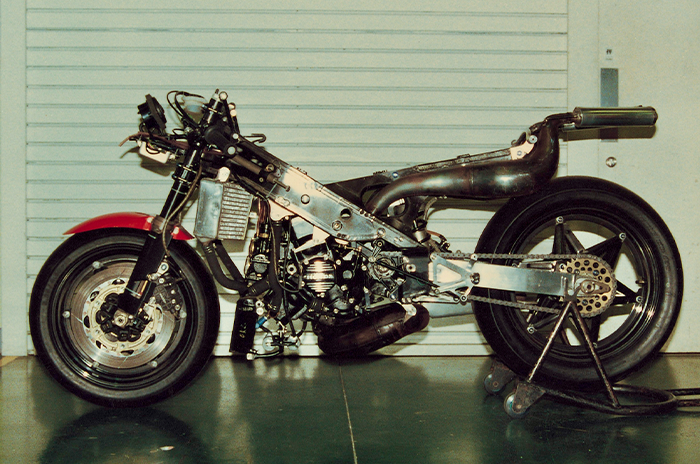

A little before the development of the NV0B, around 1982-83, HRC conducted research on the ULF (Ultra Light Frame). As a replacement for the double cradle that had been used up until then, the search was for a new generation frame that would be light, highly rigid, fully compatible with the ever-deepening lean angle, and allow for a high degree of freedom in the layout of the engine, etc.

One of the things tried out was a twin-spar frame with CFRP (carbon fiber reinforced plastic) for the spar. They built an actual machine using the NS500's V-3 engine and components, and tests were conducted in strict secrecy. However, the rider, Takao Abe, known for his high evaluation ability, said, "This is no good," and the project was shelved.

This carbon frame is an example of ULF research and has no direct technical connection to the aluminum frames with two ribs inside used in the NV0B and other models. Kaoru Yamamoto, a frame design engineer, said, "At the time, HRC's frame builders were all thinking about different things. But the requirements were the same, so in the end, everyone thought about the same things."