POINTWhat you can learn from this article

- Company headquarters Honda Aoyama Building reflects philosophies of founders Soichiro Honda and Takeo Fujisawa

- Safety Philosophy is the link between manufacturing and architecture

- Aoyama Building incorporates sustainable building technology looking toward the future

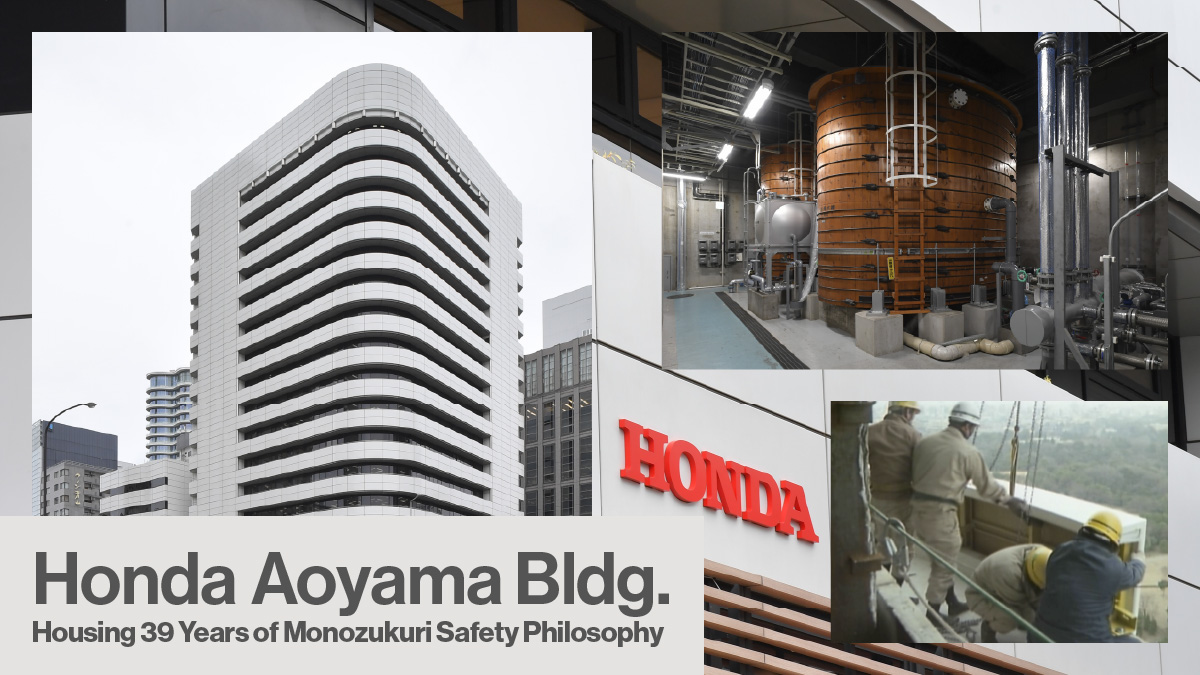

The Honda Aoyama Building, Honda’s Tokyo headquarters completed in 1985, will be reconstructed in the spring of 2025. A new headquarters building will be constructed on the same site, to be completed in fiscal 2030.

The building embodies philosophies of Honda founders Soichiro Honda and Takeo Fujisawa, and Honda’s philosophy of Monozukuri (Manufacturing): to be the most advanced in 20 years. The building’s architectural design, which incorporates Japan-first technologies, and the pursuit of safety and energy conservation, has transcended its role as an office building to become a place where technological innovation and future orientation converge. This issue of Honda Stories unravels the technologies and thought that went into every detail of the building.

Aoyama Building housing 39 years of Honda’s dreams

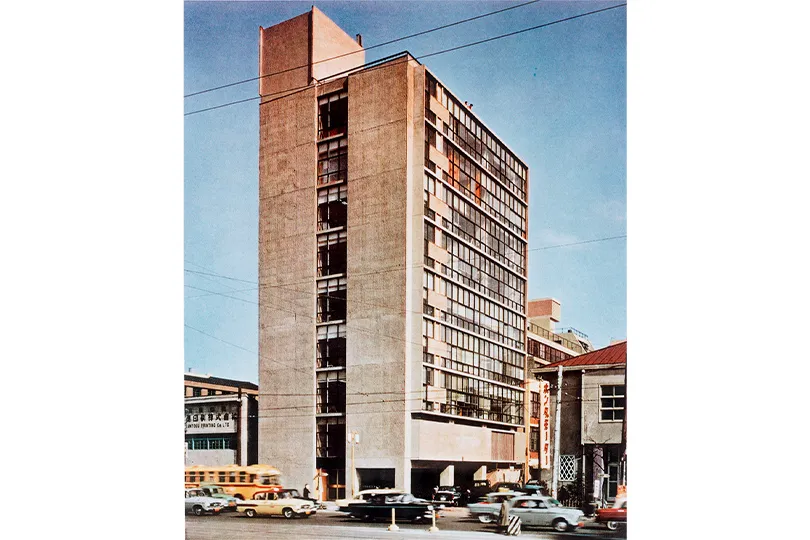

Honda grew in step with Japan’s rapid economic growth, and its history has been shaped by the vision of its founder Soichiro Honda, and Takeo Fujisawa, a key figure in management who supported Soichiro from the earliest days. A company newsletter in 1960, when the the Tokyo Yaesu Head Office Building, Honda’s first company-owned building, was completed, provided an interesting insight:

“Hundreds of thousands of people gather and disperse around Tokyo Station every day. From its ski-slope-like platforms, only a small fraction of the surging crowd comes to our building. Yet, each and every one of them comes to our building with big dreams. The time will come when this small building will no longer be able to hold their big dreams. When that happens, we will build a new building.”

In fact, Honda’s headquarters has continued to grow, changing location and form as the company’s dreams have expanded.

In 1974, Honda moved from its Tokyo Yaesu building to Harajuku. In 1985, the new Aoyama Building, Honda’s new headquarters, was completed to house its ever-expanding dreams.

Honda Tokyo Yaesu Building was completed in 1960 and housed the company’s headquarters until 1974. Demolition work started in May 2023 due to redevelopment of the surrounding area.

Honda Tokyo Yaesu Building was completed in 1960 and housed the company’s headquarters until 1974. Demolition work started in May 2023 due to redevelopment of the surrounding area.

Honda Tokyo Harajuku Building. This photo was taken around 1980. This building served as Honda’s headquarters from 1974 until 1985, when the current Aoyama Building was completed.

Honda Tokyo Harajuku Building. This photo was taken around 1980. This building served as Honda’s headquarters from 1974 until 1985, when the current Aoyama Building was completed.

Since then, the Aoyama Building has served as a symbol of Honda for 39 years to the present. While it has been visited by dignitaries from around the world, including Britain’s Prince Charles and former Princess Diana Frances Spencer, it has also provided a space that combines diversity and familiarity, where anyone can easily visit.

The construction project for the Aoyama Building was carried out in the in-house spirit of “All-Honda,” gathering members of the Honda Group as well as the design and construction teams in one planning office. In the process, company founder Soichiro Honda, enthusiastically conveyed a message to the engineers, that the building should be the most advanced in 20 years.

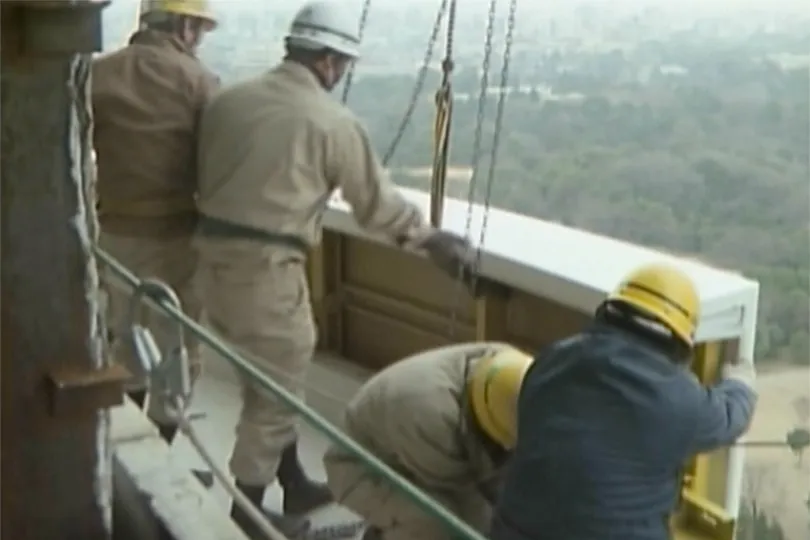

Construction of the Aoyama Building (Photo: courtesy of Hazama Ando Corporation)

Construction of the Aoyama Building (Photo: courtesy of Hazama Ando Corporation)

Incorporating safety philosophy through manufacturing in its building design

Designing the Aoyama Building was guided by three basic philosophies that can be considered the foundations of modern architecture: safety, energy conservation, and flexibility. Revolutionary at the time, these philosophies were incorporated based on Honda’s own manufacturing philosophy. In particular, as Japan is a disaster-prone country, disaster mitigation was a top priority.

Soichiro’s desire to make the headquarters building the safest building in the world was persistently conveyed to the project’s engineers. A space where people can feel safe to visit or pass through creates a sense of relief and prevents panic. Honda has always pursued safety through manufacturing, and this was a philosophy that it felt obliged to realize in the building’s design.

Steel frame was transported in the morning when traffic on Aoyama-dori avenue was lightest (Photo: courtesy of Hazama Ando Corporation)

Steel frame was transported in the morning when traffic on Aoyama-dori avenue was lightest (Photo: courtesy of Hazama Ando Corporation)

Installing aluminum molding plate on exterior wall (Photo: courtesy of Hazama Ando Corporation)

Installing aluminum molding plate on exterior wall (Photo: courtesy of Hazama Ando Corporation)

The design of the evacuation exits to ensure the safety of the employees was the subject of many iterations of planning and verification. Soichiro, taking into account the human tendency to flee to the four corners of a building in the event of a disaster, adopted a structure that allows access to the evacuation stairs from the balconies of each floor. He was emphatic that government standards were only the minimum, and design must not interfere with safety.

Design that allows people to evacuate safely without the help of machines: this approach can be seen as the challenge to incorporate Honda’s safety philosophy into the building.

The balcony was designed to prevent windows from falling and fire from spreading, which is expected in skyscrapers in the event of a disaster. Professor Nobuo Fukuwa of Nagoya University’s Disaster Mitigation Research Center evaluated the building in later years, saying that the ground was so strong that no piles were needed and that it had achieved a high level of earthquake resistance.

In addition, the Canadian cypress barrels on the B3 level of the Aoyama Building is another facility that represents Honda’s spirit of hospitality to its employees and local residents.

The water, also known as “Soichiro’s water,” stored in two large 35-ton Canadian cypress barrels has been provided free of charge to visitors to the Aoyama Building since its completion, and has also served as drinking water in times of disaster.

The barrels are said to be inspired by the water purification system used by a French restaurant nearby when head office was located in Harajuku. The same water purification system as the French restaurant was initially planned for the Aoyama Building, but it was decided to use a Canadian cypress barrels instead, because wooden barrels, the mainstream in the U.S., purified water and eliminated the calcium odor, making the water mellower.

Canadian cypress barrels

Canadian cypress barrels

Basement has storage room for stockpiling supplies

Basement has storage room for stockpiling supplies

In accordance with its basic philosophy of “No production without safety,” Honda had introduced a system to evaluate and commend all kinds of safe operations for a large number of workers, led by the contractor Hazama Gumi (now Hazama Ando Corporation), whose company policy was “Safety takes priority over everything else.”

As such, safety in the Aoyama Building had been considered throughout to such an extent that experts had considered it unique in the depth of its safety design.

Designed like a Civic: the challenge to realize environmental performance 20 years ahead

In addition to safety, the second requirement in designing the Aoyama Building, energy conservation, realized technologies that unfaded to this day: in FY2021, primary energy consumption was reduced by approximately 60% compared to FY1990, the base year of the Kyoto Protocol. The energy efficiency rating of the exterior at the time of the 13th JIA (Japan Institute of Architects) 25 Year Award (FY2013) was around 32% better than the base value, and earned the equivalent to the highest CASBEE*¹ (Comprehensive Assessment System for Built Environment Efficiency) rank.

*¹ An environmental performance evaluation system for buildings developed in 2001 by a committee established within the Institute for Building Environment and Energy Conservation under the leadership of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. It is used to objectively evaluate and indicate the performance of a building in terms of how considerate it is to the global and surrounding environments, waste in running costs, and user comfort. The evaluation covers new and existing buildings in Japan.

Data for FY2017 showed a reduction of approximately 20% in CO₂ emissions when compared to the best business offices in Tokyo. Since FY2000, the average value of major office buildings in Japan has been on a downward trend, not only because of social promotion of energy conservation and the renewal of facilities to a degree, but also because reductions in energy consumption have been promoted since 2010.

Of note is the Aoyama Building’s unique ceiling lighting. The lighting, which is not in conventional lines but square-shaped units, achieves a uniform light environment. The illuminance of lighting in the building was determined based on medical and physiological data, reexamining the illuminance of typically overly bright office lighting in Japan. This was not only a consideration for employees and work productivity based on ergonomics, but also a major factor in energy conservation.

Lighting positioned in square-shaped configuration

Lighting positioned in square-shaped configuration

The architectural designers were constantly told by Honda’s staff to design the building “like a Civic.” The Civic CVCC, which was a huge hit when it launched in 1973, had tires positioned at the corners and a solid footing, looked compact yet it was spacious inside, easy to drive, and offered excellent performance.

It was also the first car in the world to comply with the Muskie Act (the U.S. Clean Air Act of 1970), one of the strictest emission regulations, which at the time was criticized as impossible to achieve by automobile manufacturers around the world. This pursuit of safety, comfort, and environmental performance was applied to the building’s architecture.

Civic CVCC launched in 1973

Civic CVCC launched in 1973

Among the energy conservation measures, the design team focused most on a natural air-cooling system*² that utilized natural energy. This was developed through trial and error in cooperation with engineers in the fluid dynamics field at Honda R&D.

*2 Cooling load treatment is required for zones in a building that are exposed to outside air and sunlight, such as near windows and walls, because of their high air conditioning load and large temperature fluctuations. This system incorporates outside air cooling into the cooling treatment to achieve high energy savings.

The adoption of this air-cooling technology had a great impact on the engineers of the time. They were excited, saying, “Other skyscrapers use water cooling [chilled water circulating], but the Aoyama Building uses air cooling [outside air].” Although basic research on this technology had been conducted in Japan, there were no examples of its implementation yet.

Furthermore, the Aoyama Building pioneered the use of a computer-controlled air conditioning system. Although this technology did not initially produce significant results due to hardware and software limitations, with time, the value of its design became apparent, and it has now been inherited as a technology that is widely used throughout the country. Although it took several decades to achieve results, the Soichiro’s desire, for the building to be the most technologically advanced in 20 years, had proven to be correct.

From office to a place of thought: office space embodies hands-on approach

Regarding flexibility, the third basic philosophy, the theme was to realize a sustainable architecture that could respond to organizational and technological changes, as well as social and environmental transitions. To this end, the idea of long-term use was adopted, where the building was not made to be perfect, but to leave room for future development.

Symbolic of this flexibility was the FCC (Flat Cable Conductor) under-carpet wiring system, covering the largest floor area in Japan. This technology allows power to be supplied anywhere within the building, thus allowing flexible office equipment placement. In other words, it allows flexibility in layout changes and has transformed the interior of conventional offices. This technology was later updated to the wiring system used in OA floors that had become popular.

Another example that symbolizes the flexibility of the Aoyama Building was the adoption of the “One Big Office” concept. The office area of the Aoyama Building consists of a lattice beam and four pillars spanning nearly 19 meters, and is designed to provide a clear view of the entire space. The height of the cabinets is also standardized at three levels to ensure an unobstructed view. These innovations embody Honda’s corporate stance of promoting free and vigorous communication among employees. The design was based on the advice of Kai Umemura, a structural engineer and professor emeritus at the University of Tokyo at the time, to ensure a large space while also achieving a high level of earthquake resistance.

The One Big Office concept is also applied to the boardroom, which is a large, flat room with no individual offices. This symbolizes the spirit of Waigaya*³ that Honda values, where all executives, including the president, can gather for lively discussions at any time.

*³ Waigaya refers to Honda’s unique culture of open-hearted discussions about dreams and the ideal state of work, regardless of age or position.

The design of the flat workspace is a strong reflection of Honda’s philosophy, which started as a small factory, and of Soichiro Honda's own philosophy of being an engineer and entrusting Takeo Fujisawa with the management of the company.

The design of the flat workspace is a strong reflection of Honda’s philosophy, which started as a small factory, and of Soichiro Honda's own philosophy of being an engineer and entrusting Takeo Fujisawa with the management of the company.

At the time, Soichiro was said to have remarked to those around him that as a company grows larger, the power of the back office (administrative division) becomes stronger, and that many companies lose momentum as soon as a new building is constructed. Soichiro, who thoroughly adhered to a hands-on approach, wanted to avoid such a situation by all means. The great inventions of the past were overwhelmingly made by small and medium-sized enterprises rather than those invented by large corporations. Therefore, he said, “Never forget the town factory spirit.” The most important guideline of the Aoyama Building, “From an office to a place of thought,” came from this idea.

The engineers of that time look back and say that the factory was filled with the idea of everyone thinking, and making, together. Soichiro’s desire not to maintain this spirit in the Aoyama Building is reflected in the rewarding of improvement proposals, the idea contest after working hours at the factory, and not making the carpet in the head office floor more luxurious than at the factory.

Takeo Fujisawa reflected on his interactions with the architectural designers when the Aoyama Building was first designed.

“The world has changed so much, and we are about to enter the 21st century, so what is different about this from the buildings of the 1960s? It cannot be a normal design and structure that the world is used to, which is embarrassing. Honda takes pride with its consistently high overall level of technology. It is very easy to design a factory building to be user-friendly, but the headquarters is shapeless. This is not good enough. Also, Honda was not made by one person. I wanted the opinions of everyone who will use this place, as they are thinking hard, to be reflected. That is what I told the architects, which resulted in the current building (Aoyama Building). That is why no other company can imitate us.”

As many as 700 Honda engineers were said to be involved in the Aoyama Building construction project. Takeo Fujisawa’s will and Soichiro Honda’s philosophy. Although the two founders had very different personalities, their last major project, to pass the baton to the next generation, was today’s Aoyama Building.

To carry on the philosophy of the founders in the Aoyama Building, which changes its form with the times and with Honda’s new dreams. This is the next major task for Honda.

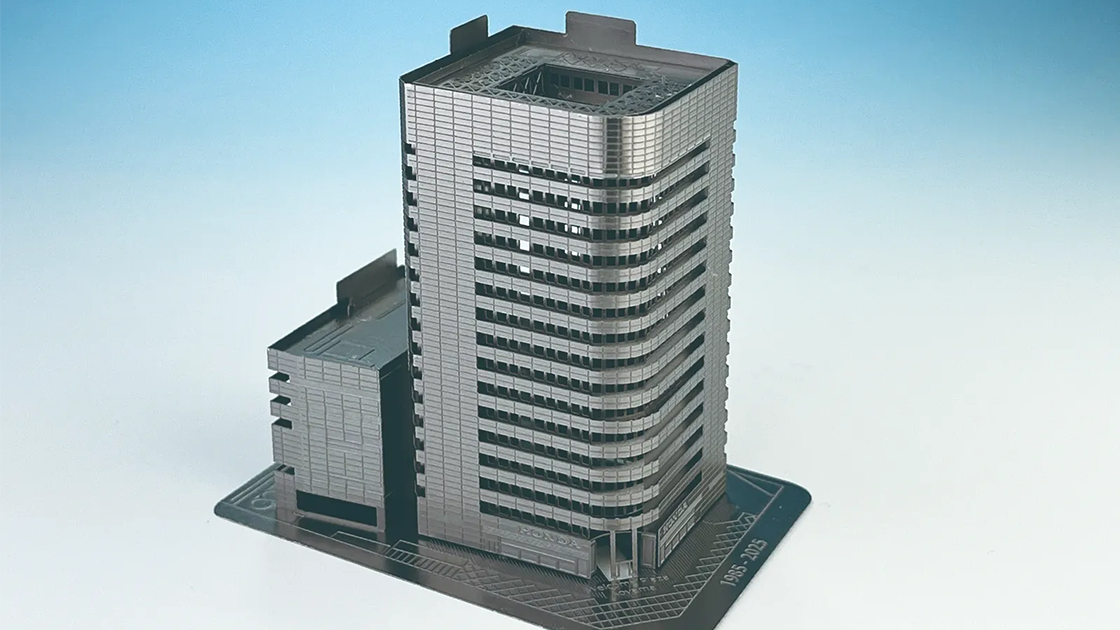

As part of the Aoyama Building closing event, a 1/1250 scale metal etching model (assembly kit; right) will be available for purchase. In addition, Faith Co., Ltd. is accepting reservations for a limited edition of 2,000 assembly blocks (left), from January 23, 2025 to April 30, 2025, with delivery in late April 2025)

As part of the Aoyama Building closing event, a 1/1250 scale metal etching model (assembly kit; right) will be available for purchase. In addition, Faith Co., Ltd. is accepting reservations for a limited edition of 2,000 assembly blocks (left), from January 23, 2025 to April 30, 2025, with delivery in late April 2025)