Purchasing Supported Honda’s Foray

into the Automobile Industry in its Early Days

The seven tools of purchasing to calculate cost

The seven tools of purchasing to calculate cost(date stamp, correction stamp, weight calculator, roller (a tool used to measure dimensions by rolling on a drawing), and slide rule)

Shirako plant opened in 1952

Shirako plant opened in 1952

“Don’t Stop the Conveyor Belt”

Honda began in Hamamatsu City, Shizuoka, in 1948, and from the time of its founding at the Yamashita Plant, purchasing staff acted in accordance with his words: “Don’t stop the conveyor belt.” The basic role of the purchasing department is to procure all materials needed for production without delay, and its operations are carried out to ensure that a fixed amount is ready at a fixed time and in a fixed quantity.

At the time of its founding, Honda’s designers always considered the effective use of parts available in the market when designing products. When it came to parts in the market, the purchasing department is at the forefront of this process. The people in charge of procuring the necessary parts and materials diligently searched the market and suppliers.

In 1950, when the Tokyo Plant was opened, the internal production machinery was not yet in place, so purchasing staff, even those who had just joined the company, had to spend two to three months scrambling to find suppliers with the help of their seniors. Many of the suppliers were introduced to through existing suppliers, or staff would find them in the phone book, make contact, and visit them. Unlike today, Honda and its business was well known at the time, so staff would have to begin conversations by explaining Honda and its motorcycles.

In January 1953, Honda moved its head office from Hamamatsu to Tokyo where it centralized purchasing, accounting, and sales functions. At the time, there were few automobiles on the roads, and some suppliers delivered parts to Honda carrying backpacks. Since the management system was not yet developed, it was impossible to respond to sudden changes in plans at the production site by placing orders at the head office and delivering the parts to the plants. As the plants were unable to fulfill their responsibilities until delivery, the production line would stop, resulting in complaints from the plant workers.

“At this time, purchasing should not be in the head office.”

The purchasing department came to this conclusion, that the head office was not the right place for it at the time, and moved its operations to the Saitama Factory’s Shirako Plant in July, six months later. Large items such as magnets and lights were centrally arranged at the Saitama Factory, while daily reminders to suppliers for parts deliveries were handled at the Saitama and Hamamatsu factories.

Three years later, as part of management modernization, Honda examined its organizational structure and concluded that purchasing was necessary as a head office function, and in March 1956, the Purchasing Department was established. From 1957 to 1958, a purchasing management system was created to streamline and improve the accuracy of office management from order placement to delivery as the groundwork for a purchasing management system.

Many of the methods introduced during this period, such as price and quantity classifications (introduction of the master concept and creation of procurement standard tables), introduction of the parts compensation concept, and a scheduled price system for materials supplied for a fixed fee over a certain period regardless of market fluctuations, formed the basis for the current purchasing and cost management systems.

In 1960, the Suzuka Factory began operations and mass production of the Super Cub C100 began in earnest. Honda began to seek and develop business partners in the Chubu and Kansai regions, which until then had been concentrated in the Kanto area. This was done in order to contribute to the development of the local communities, which is a Honda policy, and at the same time to improve the efficiency of deliveries of parts and other items. The head office's Purchasing Department advertised in newspapers, and the response was so strong that nearly 500 companies applied.

Honda then entered the automobile market, launching the T360 and S500 in 1963. As economy boomed, most of the companies in the industry were planning to increase production by 50 to 100 percent. The N360, launched in 1967, was a huge hit as soon as it was launched, and the initial plan of 5,000 units per month was updated to 20,000 shortly after. While this was a welcome development, it also created a problem for the purchasing department.

A number of suppliers turned Honda down due to production capacity problems, saying they could provide up to 5,000 units, but could not handle 20,000. Some infuriated suppliers even left their molds in front of the guard station, claiming that Honda was not keeping to the agreed amount. The many suppliers declining to do business had to be replaced with other to ensure the volume of orders needed could be secured.

The N360 was supposed to be an entry-level car at an affordable price, so the production cost target was much stricter than for previous models. Honda selected suppliers (for its Maker Layout) that differed greatly from those of the past, aiming to achieve cost reductions. These efforts resulted in a rapid increase in new suppliers.

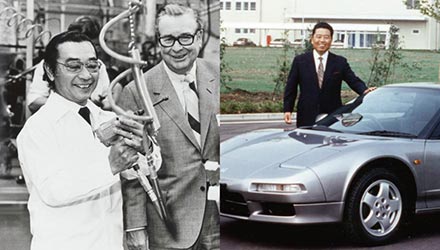

In the mass production of the CVCC engine, which complied in 1972 with the U.S. Clean Air Act of 1970, Honda decided to outsource the key components of the CVCC engine to suppliers instead of manufacturing them in-house, by implementing a maker layout that integrated the R&D, manufacturing, and purchasing departments from the development stage through to the mass production stage. Although the decision to outsource was made, the selection of suppliers was no easy task, as it was difficult to find suppliers who could satisfy Honda’s requirements of confidentiality, technical capabilities, and prototyping.

In any case, the maker layout for new technology and mechanisms required a great deal of passion and patience as a purchaser to meet the technical requirements while satisfying the purchasing policy and strategy.

Expanding Overseas to Localize Parts

HAM Marysville Motorcycle Plant

HAM Marysville Motorcycle Plant

“If we can buy good products, at a fair price, and in a timely manner, we will freely buy them from anywhere in the world.”

In September 1976, when Japan’s industrial product exports were increasing and other countries were becoming increasingly concerned about trade imbalances, Honda established the Overseas Purchasing Group within the Purchasing Department at the head office, and in 1978, the group evolved into the Overseas Purchasing Section, the first independent department of a Japanese automobile manufacturer to specialize in the import of automobile parts. It began its activities with the objective of following up on full-scale import activities and local procurement, and was reorganized as the Overseas Purchasing Department the following year in 1979, as Honda’s overseas procurement progressed. However, the policy of import expansion was not always welcomed internally. It was natural for the company to be reluctant to complicate matters more than necessary, such as language problems, poor communication and logistics conditions due to geographical background, and differences in business practices, when there would have been no difficulty if they had asked their Japanese suppliers instead.

In addition, implementing projects came with more challenges, such as translating drawings, contracts, QC process charts and forms used at the factory into English, and understanding complicated trade practices. Although international business transactions are commonplace now, at the beginning of overseas purchasing, there was no accumulated know-how, and there were many obstacles. The purchasing managers of the time overcame these problems one at a time, to build the foundation of today’s overseas purchasing.

In North America, Honda of America Manufacturing (HAM), a manufacturing subsidiary, was established in February 1978, and a motorcycle plant began operations the following year in 1979. Although the U.S. was an automobile superpower, it was not necessarily a favorable environment in terms of local procurement.

Although Harley-Davidson was the only motorcycle manufacturer in the U.S., major parts such as dampers, meters, and carburetors were being made in Japan. In other words, the country’s foundation for a parts industry was next to non-existent. In addition, while Japan had a high percentage of dependence on suppliers for materials and parts, the U.S. had by far the highest percentage of in-house procurement. In the automobile industry, even the Big Three (GM, Chrysler, and Ford) manufactured even small stamped parts in-house.

Honda believed that it was important for the company to integrate as a member of the local community, even overseas. For the localization of parts, the purchasing department had a maker layout with a target for the local procurement rate, and based on the state of the parts industry in the U.S., the local procurement rate was gradually increased.

In Europe, when the first Japan-UK automobile talks were held in London in December 1975, the British side made an offer that included the expansion of European automobile parts purchases. In response, five Japanese automobile manufacturers decided to each establish a representative office in Europe. Honda decided to station a person in charge of purchasing from the perspective of local procurement at its representative office (HELO) in Belgium, which focused on operations and services related to regulations such as certification and type approval. However, in Europe at the time, it was difficult to find parts other than standard parts that met Honda’s specifications and quality requirements. After patient investigation, the purchasing department found the possibility of local procurement and installation in Honda’s distribution base plan in Europe, and proposed it to management. The proposal took shape, and Honda Europe N.V. in Ghent, Belgium, became the first Japanese automaker (according to Honda) to establish a full-scale parts installation plant. At the end of April 1979, the Ghent plant was up and running, installing parts for the Prelude, Accord, Civic, and other models. The initial 13 locally installed parts included headlights, rear fog lights, radios, and other items, and the research conducted by local representatives and overseas purchasing department staff began to pay dividends.

The Ghent parts installation plant also served as a case study for future automobile production, and for Honda and its purchasing department, Ghent became an important plant that would serve as a pioneer for local production of automobiles in Europe.

There were two types of procurement methods used in overseas production: knockdown, in which a set of parts is sent to the factory, and local procurement. The knockdown method was further classified into two categories: “Japan-supplied,” where parts were sent from a production base in Japan, and “pass-through,” in which suppliers sent parts directly to the local plant. The decision on which method to use was consistently based on a balance of QCDD (Quality, Cost, Delivery, and Development).

In the initial stage of local production at HAM, a large percentage of parts were supplied by Japan, but as the yen appreciated, the cost advantage of supplying parts from Japan was lost. In addition, with the trend toward production expansion, HAM’s North American operation concept to build a cooperative system with its suppliers was emerging as an important issue. Furthermore, the trade friction between Japan and the U.S., which had been a concern for some time, was worsening. Japanese automakers became the target of criticism, as sales of Japanese cars were increasing while unemployment was rising among U.S. manufacturers.

In response to this situation, in 1987, then Honda president Tadashi Kume announced a five-part strategy to facilitate the North American business. In his strategy, he declared that Honda would aim to expand local procurement of parts. He believed that if Honda could be independent not only in North America but also in countries where the automotive industry’s foundation had not yet grown, and if each Honda company could create a network that complemented each other, it would not hinder the development of the automotive industry in that country and would lead to free competition. The policy was not merely a response to the strong yen and Japan-U.S. trade friction, but also a guideline for localization of parts procurement with a focus on the joy of society. This policy led to “Made by Global Honda,” which became the basic approach for expanding Honda’s production bases worldwide.

In 1986, the North America Procurement Project (NAP Project) was launched to promote an increase in the local procurement rate for North American production. In line with its policy to localize parts, Honda aimed to maximize the local procurement rate. However, there were cases where Honda’s own specifications and quality standards could not be met, and as a result, more than 30 Japanese suppliers, including technical support and joint ventures with local parts manufacturers, entered the North American market during this period.

The NAP Project acted as an intermediary between Japanese suppliers and U.S. manufacturers, promoting the integration of Japanese and U.S. suppliers and increasing local procurement rates. Although the decision to expand overseas was made by the Japanese suppliers themselves, the NAP project was also a major accomplishment, as it provided the impetus for the suppliers’ global expansion, by Honda suggesting they expand overseas in anticipation of the future, and invest in overseas expansion rather than make capital investments in Japan.

In the fall of 1989, Honda launched a fully revamped Accord (90 Accord), one of its main global models. The engines of some of its grades incorporated technical elements from F1TM engines, and its floor structure was based on the wings of the Boeing 767 aircraft, creating a car with horsepower and excellent driving performance.

During the period between the planning stage of the 90 Accord and its launch, the economy continued to improve, and the desire to deliver even better products to customers led to a series of design changes to further upgrade specifications and equipment, and enhance performance. Many of the design changes were substantial and urgent, and in order to protect the production line while implementing these changes, Honda needed to invest in equipment, manpower, compensation processing, and other emergency measures that involved its suppliers. As a result, the actual costs far exceeded the planned costs.

90 Accord, which could only have been produced through an emergency response with the cooperation of suppliers.

The reason for this situation was that the Sayama Plant, the Accord’s production base, had launched four new models around the same time, and this was the first simultaneous launch in Japan and the U.S. The plan was pushed ahead despite being beyond its capabilities, and immediate measures were needed.

The emergency response to the 90 Accord was not just a matter of the suppliers’ fatigue or confusion over the start-up, but was thought to be caused by something more fundamental.

Was Honda being self-centered? What do the customers really want? What are Honda’s strengths? And what are the weaknesses? Honda needed to abandon partial optimization (ME-ism) and pursue total optimization (YOU-ism) so that it could demonstrate the collective strength of Honda. It needed to go back to its original purchasing belief which was to purchase good products, at reasonable prices, in a timely manner , and the three purchasing principles of fair and open trade, equal partnership, and respect for its suppliers.