Cub Stories

The Motorcycle of Japan, Resulting from Soichiro Honda and Takeo Fujisawa’s Travels to Europe.

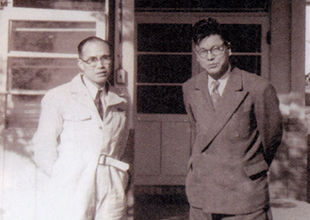

Moped or scooter? In 1956, Honda president Soichiro Honda and managing director Takeo Fujisawa traveled to Europe in search of hints to what their next major product should be. Instead, what they discovered were major differences in each country’s conditions, and how small bikes were used. They arrived at the firm belief that a new concept in motorcycles was necessary: The search of the priorities matching the times begun.

Soichiro Honda with the Super Cub's development team. After many months of trial and error and ”waigaya” (’boisterous meetings'), a unique machine unlike anything seen before was born.

From late 1956 to early 1957, Honda and Fujisawa began to form their ideas of the next major motorcycle model, based on what they had learned in Europe. The new machine would be neither a moped nor scooter. Instead, it would be something that the Japanese populace really desired, though they didn’t know it yet. An entirely new concept in handling ease and styling that would be unique to Japan, as well as to Honda. It would also need to be capable of supporting the company’s very foundations, as well as meeting the expectations of company associates who awaited their founders' return and ultimate decision.

Transmission designer Akira Akima — “At the time, everybody in the company was talking about how important it was to create a larger engine, but we also agreed that we really needed to focus our efforts on producing a popular small bike for the masses that could mark a new beginning for Honda.”

As guidelines for new development, the two men instructed their staff to “Create things that can fit in the hand” and “Create things that are easy to operate,” or more specifically, create something with four defined features:

- ● A high-powered 4-stroke engine that offers top performance, as well as being quiet and fuel efficient.

- ● A chassis and bodywork design of a size and shape that even women could easily handle and ride.

- ● A new gear shift system that doesn’t require a clutch lever to change gears.

- ● An advanced design that is also friendly, fresh and timeless.

Industrial designer Jozaburo Kimura, who had only recently joined Honda in November of 1956, recalled the moment when he first heard these policies:

Kimura — “The Old Man (Oyaji-san: Honda founder Soichiro Honda) said, ‘Since Japan’s roads are so bad, the engine has to put out at least 4 horsepower.’ He also said, ‘We’ve got to make a rugged bike that can deliver easy handling on even bad roads.’ Mr. Fujisawa added, ‘This has got to be a bike that anyone can ride, and especially one that makes women feel confident they can ride. So, the engine can’t be concealed.’”

After returning from Europe, the two thought up a new commuter bike unlike anything ever seen before.

Super Cub designer Jozaburo Kimura (2009)

In early 1957, development of the engine, a world-first 50cc OHV 4-stroke engine, began. Considering use on dominantly unpaved roads, easily operated, consistent and rugged characteristics, even at low speeds, were demanded.

Kimura — “The requirements of this 4-horsepower engine were simply unheard of. The 50cc 2-stroke Cub F auxiliary engine that we’d been producing till then only put out 1 horsepower. It followed that we’d have to boost power output by 4 times all at one go. And this was at a time when only 10 percent of Japan’s roads were even paved!”

The engine design department took the initiative in pushing development forward. While still in the initial study phase, and taking the basic structure of the frame into account, the idea of creating a horizontal engine began to take shape. Mounting the engine horizontally was considered to be the best way to facilitate straddling the bike without leaving the engine exposed. The frame also featured a bold new design, with a lower main tube that made it easier to ‘step through’ and straddle the bike. As if creating a variation of a popular type of scooter, the team proceeded on to the “slender equals easy to straddle” design study.

To prevent overheating, engine development staff made a hole in the cylinder head cover to better dissipate heat, and asked a spark plug manufacturer to develop special nonstandard spark plugs. By conceiving a host of ideas that overturned one convention after another, they eventually realized a maximum output of 4.5 horsepower at 9,500rpm, an astoundingly high engine speed and power output for the time.

May, 1958 - Soichiro Honda smiles broadly astride the Super Cub prototype. (photo from Honda in-house newsletter)

Another project that advanced almost in parallel with engine development was the design of its transmission, which meshed with an automatic centrifugal clutch. This epoch-making idea totally eliminated the clutch lever from the left-hand grip, thus allowing gear changes to be performed with only the left foot in coordination with the right hand on the throttle. This made possible the realization of a motorcycle that “soba delivery boys can ride with one hand,” words frequently quoted as those Soichiro Honda used to describe the new bike’s concept.

Akima — “The development of the centrifugal clutch itself was not all that difficult. However, figuring out how to engage and disengage the clutch in synchronization with gear shift operation proved to be complicated. On top of that, because of the kick starter ratio, the clutch needed to disengage when stopped, but it also had to engage automatically when starting.”

Owing to a structure that at first glance seemingly had to meet conflicting requirements, the team found that they couldn’t come up with good ideas quickly. Even Soichiro seemed to be thinking about it constantly, and every morning he’d drop by the design room asking, “How’s it going?”

Akima — “One day as I was leaving I said, ‘If we used a screw, we could convert the rotation of the kick action to the axial direction, but I’m afraid we might run into trouble owing to co-rotation.’ After saying this, I gave it a bit more thought, ‘Since the clutch has a certain amount of drag, it might just cancel out the co-rotation,’ Just then the Old Man came running back in saying, ‘Since the clutch has resistance, I’m sure we can make it work! I told him that was just what I’d been thinking, and he retorted, ‘Sometimes we even think alike!’ and we shared a big laugh. Eventually, we applied this method to solving the problem, and I was finally freed from the pressure of his constant visits to our room every morning.”

Soichiro Honda’s visits to the engine design department had become habitual, but it always started with discussions among the engineers. There were numerous times when Soichiro joined the discussions as various opinions were being exchanged across department boundaries. To figure out the ideal structure, everybody spoke honestly and open-mindedly, regardless of age or position of responsibility. They used to say that whenever the discussions became heated, if Soichiro came up with a bright idea, he’d pick up a piece of chalk and start drawing a diagram of the structure on the blackboard, which would invariably spread out onto the floor. In such cases, a crowd of engineers would soon gather with interest, muttering “What’s happening?” And if one of them expressed his opinion, then the people hovering around the diagram would begin to share their own views without regard to which department or job they were responsible for.

It was widely regarded that many great ideas gradually took shape through this process. Such free and vigorous discussions in a creative atmosphere led to the original form of waigaya, or the ‘boisterous meetings’ that eventually came to represent Honda Motor’s corporate culture. In some cases, discussions became extremely heated and some individuals would get overly excited. Additionally, Soichiro’s shouts of “Baka-yaro!” (Stupid idiot!) are said to have been heard many times.

Kimura — “Since the automatic centrifugal clutch was a totally new mechanism, it couldn’t be developed overnight, so it goes without saying that its development proved to be difficult and required a lot of time. Mr. Akima never gave up, and single-mindedly came up with eight separate designs. His tremendous efforts were certainly worthwhile. That clutch turned out to be an especially important feature of the Super Cub, and made the bike so convenient and easy-to-handle that women wanted to ride it as well.”