Machine Concept: Creating a completely new road racer instead of following on from the NSR500

MotoGP was born in 2002 with a major revision of the regulations for the top class of the Road Racing World Championship. However, there was no change to either the length of the race or the target, which was to be the fastest. The major changes related mainly to the engine as well, with the existing GP500 road racer technologies being able to be used as is for the chassis.

In other words, motorcycle manufacturers continuing to compete from the 500cc class, as the previous top class of the championship, entered the new series with their GP500 racer chassis but with the previous two-stroke engines swapped out for new four-stroke MotoGP engines. Honda was different though, taking the opportunity to develop a completely new road racer.

Honda’s NSR500, its existing machine in the top class, was the most powerful machine in that 500cc class. Its strength was particularly overwhelming during the period from 1994 through 2001, taking out the world titles for both individuals (riders’ title) and manufacturers (constructors’ title) for seven of those eight seasons. Consequently, it was thought that Honda’s NSR500 chassis combined with a newly developed four-stroke, 990cc engine would continue this winning run. However, Honda did not take that option. Instead, it perceived the change in regulations as the perfect opportunity for taking a new direction with its road racers.

NSR500 (1997 model), winner of all 15 rounds of the series

The concept on which Honda developed its new MotoGP machine was “ease of riding.” This might seem obvious, but while the existing NSR500 was the most powerful of the two-stroke era machines, it was by no means easy to ride. At the same time, while it might be natural to assume top-class racing bikes are not easy to ride, even the best racing riders in the world are unable to fully utilize the performance of a machine that is really difficult to ride. With the introduction of four-stroke engines to the MotoGP, control of engine output could be much more precise. Therefore, Honda felt it was important to create a machine that was easy to ride and that could fully utilize its performance in competition.

The four-stroke, 990cc engine provided around 30% higher power than the NSR500, but the major tasks for developers was to create a machine with output characteristics that were as linear and user-friendly as possible in relation to throttle operation by the rider, and to achieve a machine that was light to handle while having lots of power.

The new machine developed by Honda for the MotoGP was called the “RC211V.” The “RC” in the name established its lineage as part of Honda’s motorcycle works racers that began in the 1950s. The “211” indicated that this machine was Honda’s first top-class road racer of the 21st century, and the “V” stood for a V-type engine, the Roman numeral V for five cylinders, and a symbol for victory.

RC211V (2001 prototype)

Chassis: A flexible frame with a focus on concentration of mass

For many years, the standard seating position for riders of road racers competing on paved race courses was a comparatively rearward position with the upper body in a full forward-leaning posture. On the other hand, the seating position for riders of off-road motorcycles like motocrossers was a posture with the upper body more upright. This posture gives greater freedom in handling, which is important when decelerating to enter corners on uneven terrain. In this case, the rider has to deliberately slide the seating position to the rear to achieve the higher rear wheel load required for exiting the corner. This is why the seats of off-road motorcycles are flatter and positioned to facilitate such weight shifts.

Honda incorporated this rider position philosophy from off-road motorcycles into the RC211V. With the seating position further forward than on conventional road racers, riders were more easily able to increase front wheel load for greater controllability when cornering. The lead developer in charge of handling stability of the 2002 model RC211V (type NV5A), which was the first racing version, was originally a racing rider who competed in the large-displacement engine class of the All-Japan Road Race Championship. He said that, while riding the test machines himself, he thought in detail about what made a road racer easy to ride, and that led to a focus on how far forward the rider could sit on the RC211V.

Valentino Rossi riding the 2002 model RC211V

Honda’s approach to ease of riding naturally included physical elements. It focused particularly on minimizing the three moments of inertia—roll (rotation around the longitudinal axis), pitch (rotation around the lateral axis), and yaw (rotation around the vertical axis)—through concentration of mass. The largest body of mass on motorcycles is the engine. With the RC211V, Honda created an engine shape that was as round as possible, with roll, pitch, and yaw moments of inertia as close as possible to each other (see below for RC211V engine specifications).

Another body of mass is the fuel tank. The specified fuel tank capacity of a four-stroke MotoGP machine in 2002 was 24 liters, so the mass of fuel alone when the tank was full was about 18 kilograms (kg). Of course, the mass reduces as the race progresses, but Honda used its innovation and creativity to develop an RC211V fuel tank capable of holding that amount of fuel.

The majority of motorcycles around the world have their fuel tanks positioned above the engine and in front of the rider, whereas around half of the 24 liters of fuel carried on the RC211V was actually under the rider’s seat. To achieve this, Honda developed a special tank shaped like a horse’s saddle. In addition to lowering the center of gravity compared to a machine with a normal tank, Honda’s tank helped suppress the impact on handling that occurred as fuel was used and the center of gravity changed. In later years, all the other motorcycle manufacturers adopted this same low center of gravity tank layout, which became the standard for MotoGP machines, but the 2002 model RC211V (type NV5A) was the pioneer of this design.

RC211V (2002 model) fuel tank

The biggest different between the RC211V chassis and that of the previous NSR500 was chassis rigidity settings. To support its large engine output and the related high gripping power of its racing tires, it needed a highly rigid chassis. However, chassis rigidity includes not only longitudinal and lateral bending rigidity, but chassis torsional moment-related rigidity as well. As a machine in the top class, the NSR500 had high rigidity setting in all areas, without exception, as engine output and tire performance increased over the years.

The problem with motorcycles is that a rigid chassis, with stiffness in all directions, makes it difficult to achieve good steering performance. With the RC211V, Honda decided to significantly reduce lateral bending rigidity, with the frame setting being 17% less rigid and the swing arm setting being 12% less rigid than the NSR500. This meant that the chassis would bend in the lateral direction.

Nevertheless, Honda increased torsional rigidity by 23% for the frame and by 29% for the swing arm compared to the NSR500. This was because road racers are still leaning over when they enter acceleration mode in corners, so higher chassis torsional rigidity is desirable for delivering the traction needed to efficiently connect engine output with tire grip. Specifically, it is preferable that positional relationships between coordinates of the steering head pipe, swing arm pivot, and rear axle move as little as possible during acceleration when the chassis in a leaning state. Chassis torsional rigidity was increased for this reason. With the RC211V in particular, Honda wanted to provide more torsional rigidity than the NSR500 because the RC211V engine output was about 30% higher and machine weight was 15 kg heavier.

Finite element method (FEM) analysis of frame rigidity for the NSR500 and RC211V

NSR500

RC211V

Using the standard manufacturing method at the time, increasing torsional rigidity of the frame and swing arm would have resulted in increased lateral rigidity as well. For this reason, Honda took a new approach to developing the shape and structure of the frame and swing arm for the RC211V. Having entered the 21st century by that time, Honda was able to fully incorporate computer-aided engineering (CAE) analysis into design of the parts.

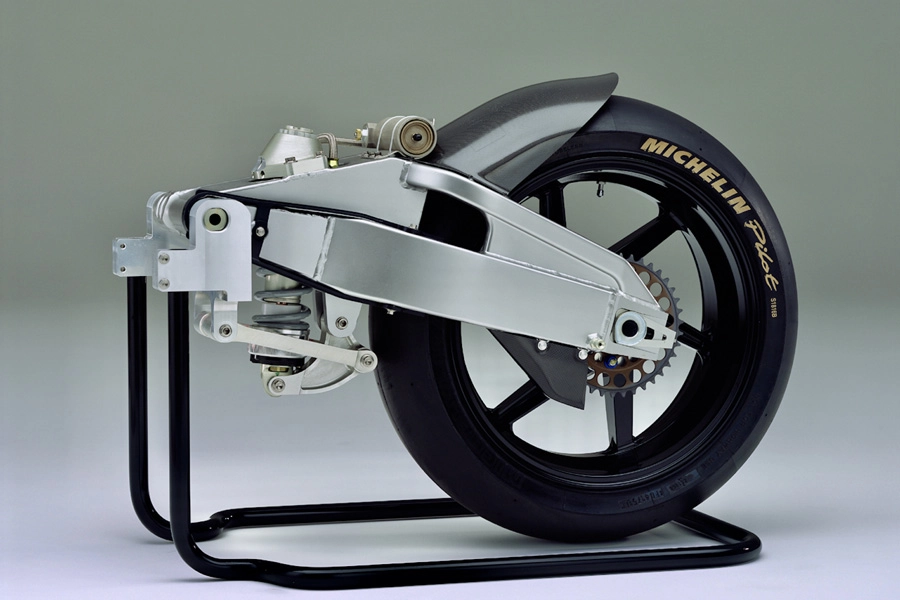

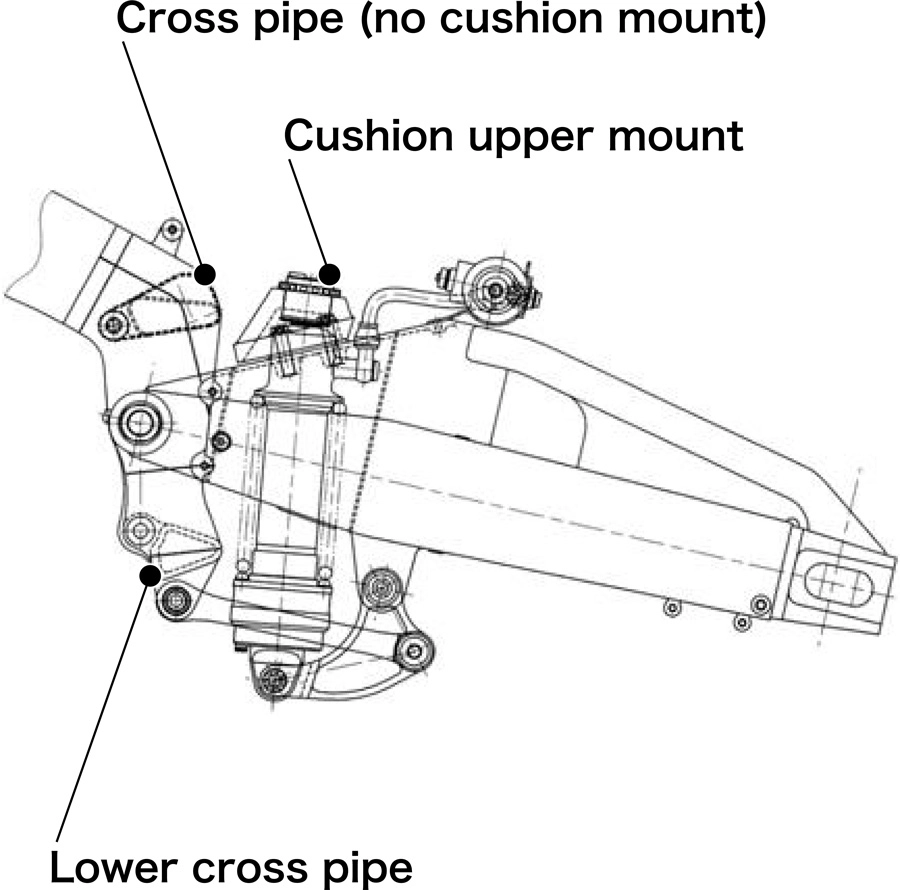

RC211V Unit Pro-Link rear suspension

One of the main characteristics of the RC211V was use of Unit Pro-Link for the rear suspension.

The rear suspension of motorcycles comprises the rear arm (swing arm) that moves up and down while supporting the rear wheel, and the damper and spring (often collectively called the ‘cushion unit”) that controls this vertical movement. The cushion unit is usually mounted to the motorcycle chassis (frame or seat rail) from the top, but there are two main types that are mounted from the bottom. The first is a direct mounting to the swing arm, and the second is a mounting via a linkage, which is commonly known as “linkage suspension.” Honda used the linkage type of rear suspension for the first time in 1981 with its CR250R and CR125R motocrossers. It called the technology “Pro-Link” based on it being a “linkage-type” suspension system that “progressively” varies load according to suspension stroke.

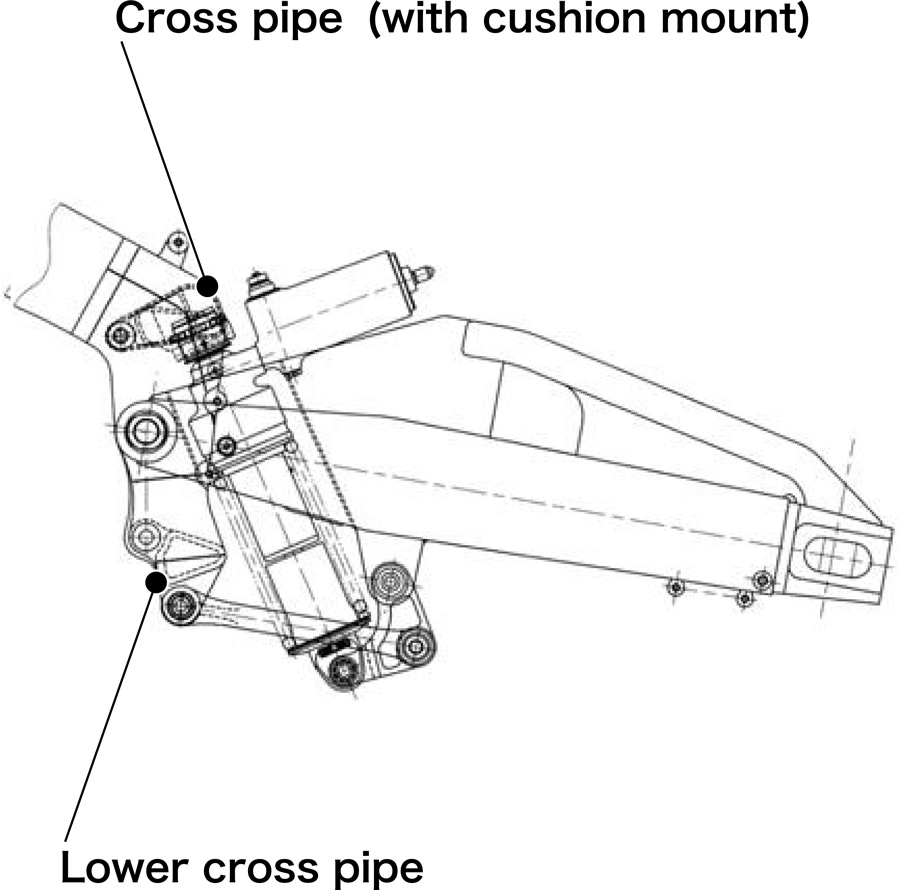

From the beginning of the 1980s, the majority of Honda motorcycles have employed Pro-Link rear suspension regardless of whether they were regular street bikes or racing machines. And all of these motorcycles used the bottom-link type of suspension, with the top of their cushion unit mounted to the cross pipe, which is a part that connects the left and right parts of a frame.

However, Honda wanted to avoid this configuration with the RC211V because direct transfer of rear input loads led to twisting of the overall chassis when bending rigidity was lower in the lateral direction. This was when Honda started using Unit Pro-Link as a suspension system without mounts on the frame for the top of the cushion unit.

With cushion unit upper mounts provided on the reinforcing structure located close to the swing arm base, the Unit Pro-Link rear suspension system works entirely through the swing arm. While originally developed by Honda for street bikes, this technology was adopted for the RC211V when the development team heard about this characteristic. This led to a chassis structure without rear load inputs and to a dramatic expansion of design freedom in terms of a frame not directly connected to the rear suspension. It also led to the realization of a low center of gravity tank layout for the RC211V.

Standard Pro-Link

Unit Pro-Link

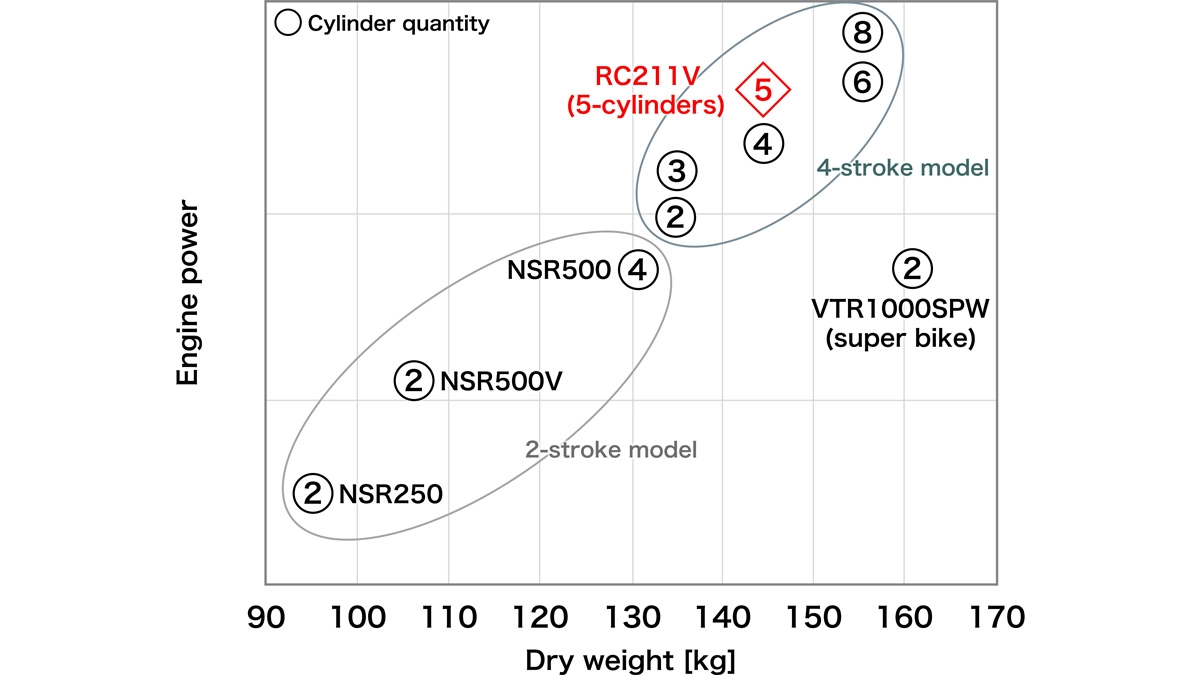

Engine: Unique choice of a V5 engine layout

From 2002, with the introduction of MotoGP as the top class in the Road Racing World Championship, minimum weight of the machines was set according to the number of engine cylinders, with 3-cylinder engines or smaller set at 135 kg, 4- and 5-cylinder engines at 145 kg, and 6-cylinder engines and larger at 155 kg. On top of this, Honda proposed an engine that was compact, had excellent mountability, and had equal roll, pitch, and yaw moments of inertia.

Honda carefully investigated a range of engine types for its RC211V. It examined the three major elements of vibration, engine geometry, and engine weight matched with everything from single-cylinder to 6-cylinder engines, and in-line (often called “parallel” when referring to motorcycles) or V-type cylinder layouts.

The majority of motorcycle engines employ a transverse-mounted engine (with the crankshaft mounted in the lateral direction). It was therefore thought that the most natural choice for Honda would be a four-cylinder V engine (V4) for its RC211V. However, Honda rejected the idea of a V4 for the RC211V because the 90 degree (°) V-angle (angle between the two cylinder banks) required to cancel primary vibration (vibration at the frequency of crankshaft rotation) resulted in the engine being too long in its longitudinal direction. While an in-line four-cylinder engine would have been shorter in its longitudinal direction, it was longer in its lateral direction. Even when fitted with a balancer, secondary vibration (vibration at twice the frequency of crankshaft rotation) remained, so Honda rejected this option as well. The greater the cylinder number, the easier it is to achieve high engine output. However, because of the many downsides of a six-cylinder engine, including that it would put the motorcycle in the heaviest class and would result in much faster tire wear, it was a no-go from the very start of Honda’s deliberations.

Engine cylinder deliberations in relation to machine weight

But what about a three-cylinder engine? While a V3 is not that different in size to a V4, a balancer was required to cancel vibration, so this layout was rejected during deliberations by the engine developers, without making it to the chassis developers’ desktop. On the other hand, an in-line three-cylinder engine was a strong possibility, with the RC211V engine developers initially considering it the most likely choice of engine. While falling behind an in-line four in terms of engine output, the weight classification of 135 kg was 10 kg lighter than a four-cylinder machine, so it caught up in terms of the power-to-weight ratio. The 10 kg lower weight itself also contributed directly to a longer life for the tires. Nevertheless, vibration was an issue with the in-line three. While a balancer would have canceled this vibration, the balancer is a heavy part and Honda did not want to just give up and create a heavy racing machine.

In the middle of this difficult decision, the engine developers heard an unexpected throw-away comment from the lead of Honda’s motorcycle product planning department. “Wouldn’t it be interesting, and just like Honda, to develop a V5?”

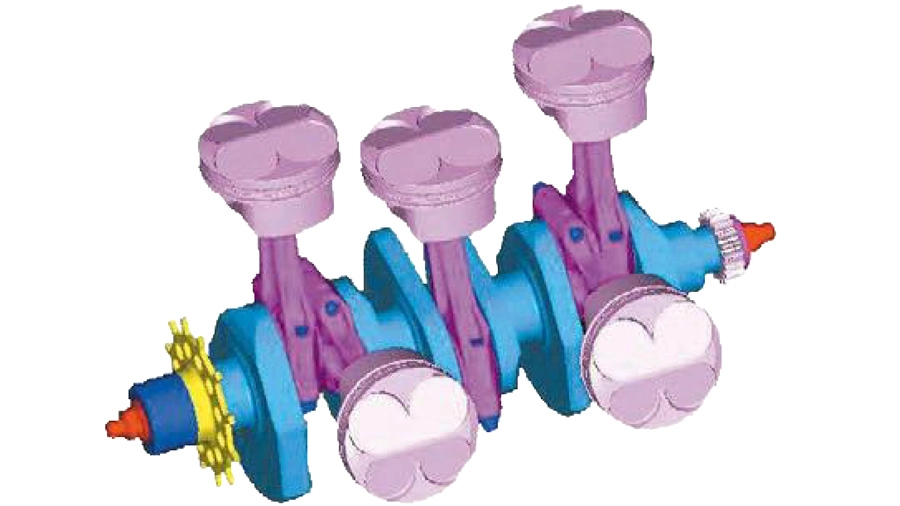

When they initially heard this comment, the RC211V engine developers could not be bothered responding seriously. However, they drew up a rough configuration design for the V5 anyway and, against all expectations, thought that it might actually work. Giving this idea a second look, they found that both primary vibration and coupling vibration (vibration between cylinders due to different crank pin angles) could be canceled without having to use a balancer. Specifically, primary vibration was eliminated by applying a 50% counterweight to the reciprocating motion element of each cylinder and offsetting the imbalance by 25% for each of cylinder #1 (front bank left side) and cylinder #2 (rear bank left side), and cylinder #4 (rear bank right side) and cylinder #5 (front bank right side). The remaining 50% (25%+25%) was offset for cylinder #3 (front bank middle). Also, because cylinders are symmetrically laid out around cylinder #3 in a V5 layout, coupling vibration was theoretically non-existent.

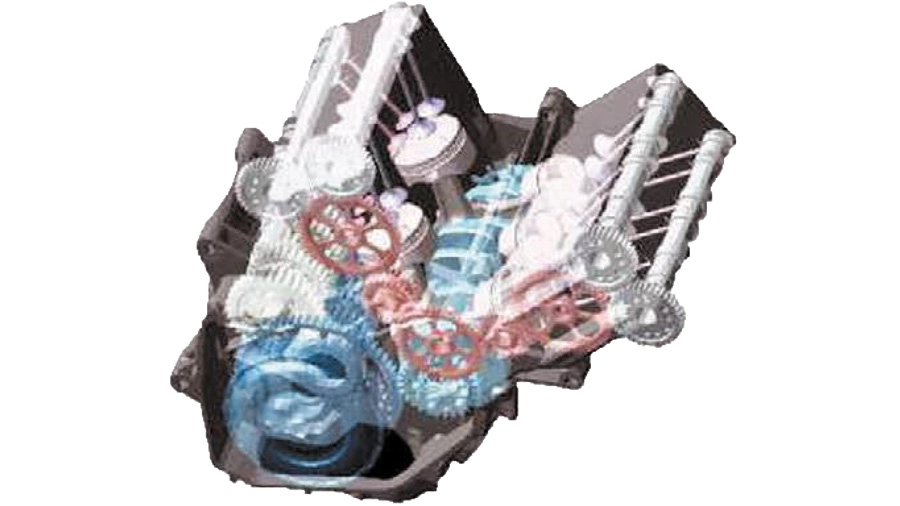

RC211V V5 engine cutaway view

Thus, Honda decided on a V5 engine layout, with the RC211V being the first motorcycle ever to use a V5 engine. And the decision to develop this unique technology, thanks to a simple comment from the product planning department, was a truly Honda-like thing to do.

One the decision was made to go with a V5 type engine, the next thing that had to be considered was the V-angle and ignition intervals. The developers started with a V-angle of 75.5°. They arrived at this figure through a series of mechanical calculations based on the idea that, with cylinders #1 and #2, and cylinders #4 and #5, sharing the same crank pins, the combined force on each cylinder could be counteracted by cylinder #3 in the middle. With the crank pin shared by cylinders #1 and 2 and the crank pin shared by cylinders #4 and #5 being in-phase, Honda set a crank pin phase of 104.5° (180°−75.5°) for cylinder #3, which successfully canceled primary vibration.

At the same time, the following irregular intervals were adopted for the ignition intervals.

RC211V (2002 model) V5 engine firing order and ignition intervals for each

cylinder

Cylinder #2 - (75.5°) - Cylinder #5 - (104.5°) - Cylinder #3 - (180°) - Cylinder

#4 - (75.5°) - Cylinder #1 - (284.5°) - Cylinder #2

The connection between rider and machine is much stronger than that of a driver and car. The ignition interval between each cylinder on a motorcycle, therefore, has a considerable effect on engine output characteristics and, by extension, the sensation of riding and actual traction performance. And Honda created a perfect example of this fact. With the V4 engine of the NSR500, Honda’s previous machine in the top class, for many years ignition timing was set at regular intervals for each cylinder (90° for the two-stroke four-cylinder machine). With the 1990 model of this machine, it changed the ignition interval to fire two cylinders simultaneously for each 180° rotation of the crankshaft, which resulted in improved traction performance. Pushing this improvement even further with the 1992 model, Honda adopted an irregular interval, two cylinder simultaneous firing pattern of 68°-292°, known as “Big-Bang” timing. The effect of this timing was so great that Honda’s rivals rushed to follow suit. With this successful experience and knowledge in mind, Honda adopted the above irregular interval ignition for the RC211V V5 engine as well, and that contributed to ease of riding.

Illustration of the RC211V V5 reciprocating engine

Performance: Outstanding competitiveness to win 14 of 16 rounds

During the first year of the MotoGP, the 2002 season, a total of 16 rounds were held across 13 countries. Five companies (Honda, Yamaha, Suzuki, Aprilia, and Kawasaki) each put forward their own MotoGP machines with newly developed four-stroke engines. (Kawasaki competed from the end of the season.) Honda’s RC211V competed in every round of the season, with the two riders from Team HRC (entered under the name Repsol Honda), the company’s works team, being Valentino Rossi and Tohru Ukawa. From the second half of the season, RC211V machines were also supplied to Daijiro Kato riding for satellite team Gresini Racing, and Alex Barros riding for West Honda Pons, both of whom rode NSR500s with two-stroke engines during the first half of the season.

At the end of the 16 rounds of the 2002 season, the RC211V had taken out 9 pole positions and 14 wins, recording an astounding 87.5% win rate. This result was clear proof that the RC211V, designed with a focus on ease of riding while producing around 30% higher engine output than the NSR500, was an outstandingly competitive machine.

Valentino Rossi, riding a RC211V to win the Japanese Grand Prix in the opening round of the 2002 MotoGP

Shinichi Ito, one of Honda’s development riders for the RC211V, rode for Team HRC in the 500cc class of every round of the Road Racing World Championship between 1993 and 1996. He pointed out the following outstanding aspects of the 2002 model RC211V (type NV5A).

- The power of the V5 990cc engine was tremendous. Acceleration remained strong

even after entering 6th gear, and in fact just kept on accelerating.

- Nevertheless, power output was smooth even when starting to open the throttle

from a fully closed position. While the NV5A only had very limited electronic

controls to assist the rider, the engine characteristics were quite easy to

handle.

- The riding position was so far forward that I was taken aback at first. In all

my experience on road racers, I had not seen that before. It felt like you were

right above the front wheel. But I just had to get used to it.

- However, once I did get use to it, I understood how logical that position was.

It was particularly effective for holding down the front. When riding in the

normal position, the front wheel would lift every time you accelerated, which

would make it impossible to continue riding at full throttle.

- All that aside, it steered well. When cornering, there was no need to force

your body to the inside of the turn; you could just stay in the center of the

bike. This was enabled by a chassis geometry and rider position that placed the

load firmly toward the front, and a frame rigidity that provided flexibility

when cornering through lateral rigidity that was lower than the NSR500. It also

had higher torsional rigidity that minimized the amount of shaking of the

chassis when accelerating out of corners.

- It is true that with the Unit Pro-Link rear suspension system not being

connected to the frame, the rider feels the rear tire grip to a lesser degree.

However, you just have to get used to this as well. And the suspension

performance itself is no different from the conventional Pro-Link. With the

rider receiving less information on the amount of bounce from the road, they can

be bolder in opening the throttle, and the bike has the capacity to take that

sudden increase in load and convert it to traction.

Shinichi Ito riding the RC211V in development testing

Of course, the RC211V had a lot of problems as well. To start with, the engine lacked in durability at the opening of the 2002 season, so temporary measures had to be taken to get through each race in the first half of the season. Various solutions were being implemented by HRC during that time so by the end of the season, reliability had been dramatically improved.

In terms of machine performance, there was a particularly serious problem of poor controllability under braking due to engine braking being too strong. This was the result of a conflict between the amount of torque transmitted to the rear wheel when decelerating and the actual rotating speed of that rear wheel. While the RC211V clutch was originally equipped with a back-torque limiter to adjust this mismatch, the riders felt it was insufficient. Finding a solution for this problem became an issue for the following 2003 season. This led to the development and adoption of Honda Intelligent Throttle Control System (HITCS), Honda’s unique electronic throttle system incorporating the philosophy of deceleration control.

While Honda had various problems to address, the RC211V truly dominated during the 2002 season, the first year of the MotoGP. Stamping its mark on 14 of the 16 rounds of the season, it took out all world titles that year; the riders’ title (Rossi), the constructors’ title (Honda), and the teams’ title (Repsol Honda). This proved that Honda took the correct approach in machine development when it adopted a completely new philosophy instead of attempting to drag out the success of its NSR500, the most powerful machine at the time. And the RC211V was to later become the benchmark for a wide variety of MotoGP machines.

Three RC211Vs competing in the Japanese Grand Prix in the opening round of the 2002 MotoGP