Automobile Development, a Longtime Dream, Begins

“Once when I was a kid, I ran after a Ford Model T and held my nose up to the oil that sputtered out onto the ground. I took a whiff and was thrilled by the smell. That experience led to my making automobiles today.”

These were Soichiro Honda’s words upon achieving a place in America’s Automobile Hall of Fame in October 1989.

In 1958, when the Super Cub C100 was launched, Honda decided to enter the automobile business, a dream of his for many years. In September, one month after the Super Cub C100 launched, Honda established the Third Research Section (responsible for everything from design to testing) in the Shirako Plant’s R&D Center, and began automobile development. This Section was the origin of Honda’s automobile development which continues to this day.

In May 1955, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI, currently Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry) announced a “National Car Development Program” (commonly known as the “National Car Concept”), which led to the development of k-passenger cars such as Suzuki Motor Corporation's (later Suzuki Motor) Suzulite (October 1955) and Fuji Heavy Industries’ (later Subaru) Subaru 360 (March 1958), among others.

At that time, however, Soichiro believed that automobiles needed serious commitment to be developed, as he stated in December 1959 issue of the Honda Company Newsletter (Vol. 50): “We shouldn’t rush into auto production until we conduct thorough research and are absolutely confident that every requirement has been fulfilled, including the performance of our cars and production facilities.”

Automobile development was finally underway. Seven engineers were assembled at the Third Research Section as a top-secret project. Young associates were selected, but some of them were mid-career hires with experience in developing airplanes, tricycles, and other vehicles. The section’s initial task was to develop a mini automobile that would meet the “People’s Car” concept requirements. Drawings were issued in October 1958, and a prototype vehicle was completed the following January, going under the development code “XA170.”

The XA170 made use of Honda’s renowned expertise in motorcycle racing with a forced-air-cooled, four-cylinder OHC V aluminum powerplant. Moreover, the front engine / front-wheel drive (FWD) car adopted a semi-monocoque structure with a flat floor so that it could be transformed into a sedan simply by adding rear seats. Since the prototype had been constructed specifically for test-drives, the fenders and hood were made with formed sheet steel, with patches of fabric covering sections where the roof and doors should be.

In the middle of the XA170’s tests, however, the team received an order from Soichiro himself for the development of a sports car. In the fall of 1959, they completed the 2-seater prototype. Subsequently, the team took up the development of a k-truck, this time at the request of Senior Managing Director Takeo Fujisawa.

Soichiro Honda had given the order to develop a sports car, because he thought it was better to create new demand rather than compete against more established manufacturers. He also believed that, as was the case with motorcycles, Honda should develop race cars and test them in actual competition in order to obtain as much expertise and knowledge as quickly as possible, in order to elevate Japan’s automotive industry to a level of the international manufacturers.

Fujisawa, on the other hand, suggested that the team develop a k-truck because he knew from society’s needs and market data that the demand for automobiles was mostly in the category of commercial vehicles. He had also considered the fact that Honda could sell its automobiles through motorcycle dealers.

Members of the 3rd Research Section had developed two models, a sports car and a k-truck, through repeated tests.

Free Competition Spurs Industry Growth

MITI, in May 1961, issued a basic administrative policy regarding the automotive industry (subsequently the Bill on the Temporary Measures to Stimulate Specific Industries, or the so-called “Specified Industry Promotion Bill”).

It was a policy intended to motivate structural reform among industries nationwide, so that preparation could proceed regarding the expected liberalization of Japan’s trade. The new MITI policy identified the automobile industry as relatively less competitive in the global market, and in preparation for the deregulation of automobile imports by the spring of 1963, divided automobile manufacturer into three groups:

- 1 Passenger cars (2 companies)

- 2 Special vehicles (such as luxury models and sports cars) (2-3 companies)

- 3 Mini cars (k-cars) (2-3 companies)

MITI intended to guide these groups by taking advantage of their unique characteristics in order to strengthen their international competitiveness.

Specific measures included the consolidation of automobile manufacturers and restrictions on new market entrants. If this bill was passed, Honda, which had no experience in automobiles, would not be able to enter the market. Soichiro let his opinions on this bill be known. In a TV interview later that year, he recalled a meeting he had with the then administrative vice minister of MITI and said:

“I had the right to manufacture automobiles, and they couldn’t enforce a law that would allow only the existing manufacturers to build them while preventing us from doing the same. We were free to do exactly what we wanted. Besides, no one could say for certain that those in power would remain there forever. Look at history. Eventually, a new power would always arise. ... If MITI wanted us to merge, then they should buy our shares and propose it at our shareholders’ meeting. After all, we were a public company. The government couldn’t tell me what to do.”

Soichiro insisted that free competition would spur industry growth.

His objections, however, did not prevent MITI from submitting the bill to the Diet. It was a critical period for Honda, as if it were to pass, the company would not be able to enter the business.

“Finish the Prototype in Four-and-a-half Months”

Honda needed to secure sufficient car-production records before the Specified Industries Bill could be passed.

In n January 1962, Honda sent the order to Honda R&D to build automobiles. The plan was to develop two k-sports cars and two k-trucks, and to exhibit the prototypes at the 11th National Honda Meeting General Assembly (the so-called “Honda Meeting”) scheduled for later that year.

The new models were to be displayed at the Suzuka Circuit, then under construction, on June 5. In other words, the order was to complete development, still in its prototype stage, in four-and-a-half months.

“The Third Research Section’s design team was originally made up of seven people, but by 1961, it had grown to around fifteen. At first, I was the only one in the molding group who handled automobiles, but by then that number had also increased, making it three of us. Since the company had decided to develop two models at the same time, that number was again increased to six, as a kind of emergency measure. So, there was a six-member k-truck team, and in order to push development it was divided into two groups,” recalled Masao Kawamura, in charge of exterior design.

Although the team had worked at a ferocious pace, they would still face the challenge of reflecting Soichiro’s detailed instructions in their progress. There was no time, but the team responded to Soichiro’s passion in wanting to make the best cars possible.

As time was running out, limitations were found in the air-cooled engines they were testing, prompting them to switch to water-cooled inline 4-cylinder DOHC engines, which became the base configuration for developing two engine types; for mini sports cars and mini trucks.

Body color also posed problems. On day, Kawamura, in preparation for the moment when the dummy model would be shown to Soichiro, had painted its body reddish orange for a highly appealing look. Upon seeing the dummy model, though, Soichiro announced, “The new car is definitely going to be red, but we should use a more vivid red.” When Kawamura painted the body a rich scarlet color, Soichiro liked it very much, and was overjoyed.

At that time, however, laws prohibited the use of red or white on any auto body sold in Japan, since doing so might confuse it with an emergency vehicle such as a fire engine or ambulance. Therefore, to obtain approval for the use of red, Mitsugi Akita, then manager of the Development Management Section at Honda R&D, paid numerous visits to the Ministry of Transportation.

“Their response was cold and harsh, to be sure,” recalled Akita. “The person in charge even said, ‘I know Honda, but I’ve never heard of Honda R&D.’ All the way back to the office I felt thoroughly depressed. I was even hesitant about seeing Mr. Honda. Days went by without any results, and Mr. Honda tried to promote his idea through the various media. At one time, he wrote a column for the Asahi Shimbun [newspaper] in which he said, ‘Red is the basic color of design. How can they ban it by law? I’m aware of no other industrial nation in the world in which the state monopolizes the use of colors.’"

Perhaps Soichiro’s argument was successful. Approval was finally granted.

“It was only Honda who fought for the right to paint car bodies red,” recalled Akita, “Soon, though, the other manufacturers started using it on many of their commercial vehicles.”

Numerous people at Honda R&D had been mobilized in order to expedite last-minute adjustments to the car, continuing their work until the day before the Suzuka meeting. The development team’s schedule had been extremely demanding, taking just four-and-a-half months.

“We relied on our youth and stamina to overcome impossible odds.” (Kawamura)

SPORTS 360 and T360 Marks Honda’s Entry

into the Automobile Business,

SPORTS 500 Aimed for Global Market

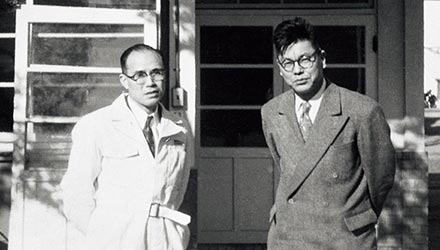

The 11th National Honda Meeting General Assembly was held on June 5, 1962, at the soon-to-be-completed Suzuka Circuit. Soichiro drove the SPORTS 360 prototype onto the racing track. Yoshio Nakamura, manager of the development project, was in the passenger seat as the red sports car drove across the grand stand. This was Honda’s maiden voyage into the automotive business, symboling the pursuit of Soichiro’s lifelong dream.

The SPORTS 360’s entrance was impressive to the representatives of Honda’s franchised dealers who had gathered at Suzuka. They, after all, had wanted to have products they could sell during the winter months, when motorcycle sales experienced a significant decline.

The 9th Japan National Auto Show, a thirteen-day event, was held at the International Trade Center at Tokyo’s Harumi Wharf starting on October 25, 1962. Record crowds totaling over a million attended the show, amply demonstrating that the nation was ready to take on the car culture. There was Honda, displaying its three new models: the SPORTS 360 the T360 k-truck, and the SPORTS 500 based on the SPORTS 360 with a larger body and engine. The company’s booth attracted throngs of people, sending a wave of anticipation across Japan and the world.

Honda exhibited its first automobiles, the SPORTS 360, SPORTS 500 and T360 at the 9th Japan National Auto Show

Honda’s advertisement, which offered prizes to those who could correctly guess the price of the new Honda Sports 500, was so popular that it set a record for ads of this type.

Honda’s advertisement, which offered prizes to those who could correctly guess the price of the new Honda Sports 500, was so popular that it set a record for ads of this type.

June 1963 saw a massive Honda sales campaign, as mass-production and sales approached. An advertisement, which offered prizes to those who could correctly guess the price of the new Honda Sports 500, was featured in the country’s leading newspapers. More than 5.7 million entries (the record for an ad of that type) were received. The price of 459,000 yen was subsequently announced in July, just a month after the ad had run, surprisingly much less than industry norms.

The T360 k-truck went on sale in August 1963, and the SPORTS 500 sports car hit the market in October as the S500.

The SPORTS 360 unfortunately never made it to the market. Fujio Ishikawa, who was involved in the car’s body design at Hamamatsu Factory’s Welding Section, explained:

“When we were working on the car based on a 360 cc engine, the management told us to make the body wider to accommodate a 500 cc engine. Since there was only a limited demand for sports cars among the Japanese, it was suggested that we design a car that could be marketed around the world. I think Mr. Honda had been thinking globally from the very start.”

Abandoning the SPORTS 360 in favor of the S500 was also a strategy tuned for the anticipated Specified Industry Promotion Bill. By releasing 360 cc k-trucks and 500 cc compact sports cars (3 and 1 above), Honda would qualify as a manufacturer of micro-cars and passenger cars in time for the passage of the bill. Moreover, the emphasis on small cars reflected the company’s intention to enter the world market. Indeed, the S500 evolved into the S600 and S800, sold overseas.

T360 k-truck launched in August 1963

Following the T360, the S500 compact sports car was launched in October 1963.

The basic MITI policy regarding Japan’s car industry was compiled into the Bill on the Temporary Measures to Stimulate Specific Industries in March 1963, and was submitted to the 43rd Session of the National Diet. However, the session was adjourned in July without a resolution. The bill was resubmitted to the 46th session starting in January 1964, but did not pass, and was eventually abandoned. By working through the tough development period, the engineers gained much valuable experience, and their development capabilities were greatly improved.

Since the special appropriation bill forced Honda to enter the market early, it lacked a solid foundation in terms of production technology and mass production facilities.

Honda’s facilities at the time were designed for motorcycle production, just a small portion of which could be used in the making of cars. Honda contacted its existing parts suppliers for help, along with several new suppliers, all the while investigating ways to utilize the existing infrastructure. As a result, it was decided that the Wako Plant would produce engines for the T360 and S500, and bodies for both models would be built at Suzuka Factory for shipment to Saitama and Hamamatsu. Final assembly of the T360 would be done at Wako, while the S500 would be handled by the Hamamatsu Factory. Production was dispersed across Honda’s facilities through necessity.

This dispersed production lacked efficiency and had many problems, but there were certain advantages. All factories were able to acquire some experience in car production. Those involved in production at the factories obtained invaluable insight by applying themselves to develop necessary solutions on a day-to-day basis. This experience at the beginning of Honda’s expansion phase was particularly useful in building Sayama Factory (now Saitama Factory’s Sayama Plant), and ultimately facilitated the launch of auto production at Suzuka.

S500 and S600