Taking on Challenges to Expand Business into Europe,

the Home and the Largest Market for Motorcycles

In June 1961, as its motorcycle sales in the U.S. set it well on track to becoming a global company, Honda moved quickly into Europe with the establishment of European Honda Motor (EH)*1 in Hamburg, West Germany. Considered the home of motorcycles, the European motorcycle market was divided into two main categories at the time: supplier countries (the U.K., Germany, France, and Italy), and consumer countries that imported complete motorcycles or component parts sets to be locally assembled (the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, and Switzerland). Motorcycles played an important role as a means of mass transportation throughout Europe, accounting for 85% of the world's motorcycle ownership (excluding Japan) at the time, with annual demand of over 2 million units.

About two years before EH was established, the Honda Dream was exhibited at a motorcycle show held in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, and was highly praised by a British journalist who said that it could “stand shoulder to shoulder with products of top motorcycle manufacturers in Europe.” When Honda captured a long-awaited first victory in the Isle of Man TT Race in June 1961, Honda motorcycles attracted the attention of motorcycle fans, and Honda distributor office in London received a flurry of sub-dealer applicants who wanting to sell Honda products. At this point, Honda was already the world's largest producer and exporter of motorcycles.

By expanding its business into Europe, Honda could become the world's number one motorcycle manufacturer, both in name and reality. It seemed as if this opportunity was within reach. No Japanese motorcycle company had yet dared to challenge the European market. The establishment of EH in the former West Germany, which boasted traditional motorcycle manufacturers such as BMW and NSU (NSU Motorenwerke AG, which was acquired by VW and later became part of the Audi automobile brand), was a bold strategy to take on the world with its motorcycles.

- Later became Honda Deutschland

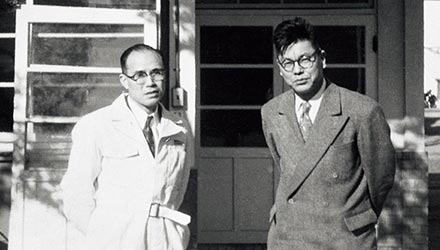

EH, Honda’s first local operation in Europe

Honda Decision to Produce in Europe

in the Face of the EEC

Once news broke of the expansion of Honda into Hamburg, one of Europe's leading commercial cities, the local Japanese embassy was the first to express their welcome. Honda vehicles were very popular in the former West Germany, and the company's technological capabilities were highly regarded. Honda vehicles were already being exported to Europe, and the company had to work to improve its after-sales service and build its own sales network.

In January 1958, EEC (the European Economic Community, the predecessor of today's European Union, the EU) was established. Although tariffs between the six EEC countries (Belgium, France, the former West Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands) were abolished to create a common market, their policy was to impose high tariffs and restrictions on imports. There was concern that once the EEC economic bloc was firmly established, countries outside the EEC region would have to pay high tariffs. The response to EEC policy was key to the future overseas strategy of Honda. Mr. Takeo Fujisawa, then Senior Managing Director of Honda, ordered Hideo Iwamura, then Deputy General Manager of Administration, to conduct a market survey on the premise of establishing a local corporation to produce and sell motorcycles in the EEC region.

Iwamura was surprised and perplexed by the sudden order, but suggested: "This is a very important issue concerning the future of Honda. So, let's tackle it by organizing a solid system first."

"I'll leave everything to you. Feel free to do what you think is best." said, Mr. Fujisawa.

By January 1962, Iwamura, along with Kenjiro Okayasu (then manager of Saitama Factory's Direct Materials Section, Materials Division) and Tetsuya Iwase (then chief of the Training Subsection, Personnel Division), organized themselves as the "Special Planning Team for the Corporate Project to Expand into the EEC Region."

The three men began researching the European motorcycle market, which at the time was estimated at over 2 million units per year, of which approximately 80% were mopeds*2. Mopeds were widely popular in Europe as they did not require a license for riders over 16 years of age, and were eligible for various preferential measures. Compared to Japan's motorcycle market of 1.5 million units per year at the time, the European market had ample potential for growth. After a three-month visit to Europe, the former West Germany and France were eliminated as candidates for production bases due to their high wage bases, and Belgium was selected, as it had many manufacturers supplying parts to German makers, but its wages were relatively low. During their visit, the research team officially selected Aalst as the site for factory construction due to its close proximity to Brussels, and the city’s enthusiasm in lobbying Honda. The company’s local production in Europe had begun.

- Mopeds refer to European bikes that are equipped with pedals. In Japan, they are called 'mopetto.' While mopeds were by law restricted to engine displacements of 50 cc or less and a maximum speed of 40 kilometers per hour (varying somewhat among countries), they also were given privileges in taxes, insurance, and special traffic rules. Moreover, the minimum operating age without a license was sixteen years. The moped, actually a kind of motorized bicycle, belongs to an entirely different category than motorcycles such as the Super Cub and scooter.

Starting Small and Growing Big

Construction of the BH plant was halted for four months due to a cold spell of 30 degrees below zero Celsius.

Construction of the BH plant was halted for four months due to a cold spell of 30 degrees below zero Celsius.

Construction of the BH plant

Construction of the BH plant

In May 1962, Honda decided to send a team of twelve to Belgium to start up the operation of the new Honda Motor subsidiary there (which was later renamed Belgium Honda Motor, or BH, in 1971). Iwamura, who had led the EEC research team, was assigned as general manager of BH in order to oversee regional production and sales. Okayasu was assigned to the factory manager's post, responsible for the construction of the factory and production operations. Iwase was assigned the job of factory administration manager, in which he would facilitate production operations.

Construction of the plant, however, was halted for four months due to a severe cold spell with temperatures reaching 30 degrees below zero Celsius. To comply with strict European labor laws, BH could not demand rush construction work. As an understanding of the passion of Japanese associates grew among locally-hired administrative associates, who would be the future BH executives, they worked energetically to carry out construction plans.

Okayasu said: “The local people had at first found it difficult to comprehend our method of first deciding on the factory's opening date and then finding ways to meet that goal. But once we reached our goal, they said, ‘This is certainly a different way of getting work done!’ After that, they really began to trust us."

Thanks to the passion of the Japanese associates and the understanding of the local associates, the BH plant was completed in eight months, including the period of construction interruption.

The first unit of Super Cub C100 rolled off the line in May 1963. It was the first motorcycle produced in Europe by any Japanese company.

The first unit of Super Cub C100 rolled off the line in May 1963. It was the first motorcycle produced in Europe by any Japanese company.

In May 1963, after construction proceeded at breakneck speed and was completed in eight months, including a period of stoppage due to extreme cold, Super Cub C100s rolled off the production lines at the new BH factory. It was the first local production in the EEC region for Honda or any Japanese company. Also, this was the first production by Honda outside Japan. However, BH was soon to face numerous hardships.

The factory’s production capacity was 10,000 units per month, a small step considering the size of the European market, which exceeded 2 million units per year.

Okayasu said: “Our approach was to ‘starting small and growing big.’ So, we were thinking that we should first work hard to increase sales and build a track record. Then we would enlarge the factory and increase production capacity."

The BH factory’s initial plan was to bring in moped engines from Japan and then to procure all other components tax-free within the EEC, but unexpected expenses continued to plague BH. In Europe, laws already mandated manufacturer responsibility for consumer protection and product reliability, and there was a provision that required manufacturers to continue offering repair parts for 10 years. This meant that BH had to hold 10 years' worth of inventory for each part, placing pressure on costs. And prices quoted by local parts suppliers increased from three to six times higher than in Japan.

On top of that, industrial standards differed from country to country, and even within Belgium there was no unified standard. When part sizes differed from manufacturer to manufacturer, product designs had to be changed. BH associates shared a common view, that they had to develop parts manufacturers on their own, as if they were drawing new procurement maps, even if it was time consuming.

Furthermore, differences in language and customs were also a source of concern for Japanese expatriates when working with local associates. Japanese expatriates often had difficulty understanding the local way of thinking which was based on a contract-oriented social structure and age-old hierarchal class system. Accordingly, opinions and perceptions would often be at odds during the process of cooperative work, but such issues were always resolved through taking time to understand each other.

Iwamura said: “Even if there were differences in language and ways of thinking, we couldn't make great products without conveying our thoughts to one another. So, I told Japanese associates to spend time and discuss with local associates about what we want to do, no matter how much time it would take.”

However, there were some people in the industry who disagreed with BH’s entry into the EEC region, where many moped makers were competing with each other, and the entry of Honda was deemed a threat. According to Iwamura, Honda focused on conveying the message: “We will conduct our business to further grow the Belgian motorcycle industry. We are planning not only to sell our Belgium-made products in Belgium but also export to other countries as well.”

This enabled BH to gradually gain an understanding of people in Belgium.

Mr. Soichiro Honda giving a speech at the ceremony commemorating BH’s first anniversary.

Challenges Faced in Foreign Lands Shaped Honda

into a Global Company

Test riding the new C310 launched at BH.

Test riding the new C310 launched at BH. The C310 did not meet local needs sufficiently

and was not accepted as BH had expected.

C310

C310

Mopeds had already been the mobility of choice for the citizens of Europe. BH was confident that if it could create a new model, closer to a motorcycle and slightly more technologically advanced than existing mopeds, it would surely gain a lot of fans. However, the new moped model, C310, BH worked hard to launch, simply was not selling as well as expected. Furthermore, soon after the C310 went on sale through the local sales network, product problems began to occur one after another, and the number of returned products increased day by day.

The C310 was not a model developed while sufficiently incorporating the needs of local customers in Europe. Actually, it was basically a remodeled version of an existing product, with minimal modifications to meet European moped regulations, put together in a short period of time, after the establishment of BH was decided and before the factory became operational.

Built based on the Super Cub, which had become a major hit in Japan the U.S., the C310 featured a four-stroke engine with reduced power compared to the Super Cub so as not to exceed the local maximum speed limit of 40 km/h in Europa at the time. It also featured pedals as with other mopeds being sold in Europe.

The body of the Honda moped equipped with a four-stroke engine was larger and heavier than the European mopeds equipped with a two-stroke engine. Therefore, the European people perceived the Honda moped more like a motorcycle than a moped.

Many C310 users used a mixture of gasoline and lubricant for two-stroke engines as a fuel, just as they did with their European mopeds, causing many cases where the C310 engine would not start.

Despite the enormous effort of Honda sales reps to introduce the superiorities of four-stroke engines and ensure that dealers provided sufficient handing instructions to their customers, sales did not increase as expected.

Moreover, what plagued BH was cash flow.

Due to the Japanese government's restrictions on the amount of foreign currency Honda could take out of Japan, BH was established with minimal funds and had always suffered from a shortage of funds.

In addition, other factors such as the inability to obtain fully qualified parts, and lackluster sales put further pressure on the operation of BH. In the end, BH was on the verge of being forced to shut down the factory.

“In the end, the basic rule of factory operation is to produce only as much product as can be sold," said Mr. Fujisawa to the Japanese associates when he paid a visit to BH out of concern for the situation.

Despite being in such a difficult situation, Honda did not let go of the dream of becoming the number one motorcycle manufacturer in the world. In addition to Japanese associates in Belgium, numerous associates and engineers of Honda Japan worked together to support production operations and product improvement efforts of BH. Nearly all locally hired associates stayed with the company and worked hard together to rebuild BH operations. And, after ten years, BH launched the Amigo, designed for the European market at a mass-market price. This moped model matched the tastes of local users and was well received in the European market.

Amigo, which realized a mass-market price

BH production line (1987)

“Know-how is not a written document. There is no one we can call and ask. Know-how is something that is amassed inside people. Whether a company can be internationalized or not depends on whether its people have know-how in them,” said a member of BH who went through this challenging period.

The hardships Honda experienced in Belgium were the local barriers where Japanese ways of thinking and methodology did not work, and the difficulty of grasping the needs of people in different countries.

Associates from various divisions of Honda, including production, sales, development, and management, experienced a difficult time in Belgium and went through a process of trial and error. Through their experiences, all Honda associates learned the lessons and gained know-how necessary to conduct corporate activities outside Japan. Such shared lessons and know-how later became a valuable asset for Honda in carrying out its corporate activities all around the world.

Establishing the Honda Brand in the Motorcycle Cultures

of European Countries

The European market cannot be defined as homogeneous. It consists of many countries and cultures, and user needs are diverse. Accurately grasping these needs and developing market-specific strategies to uncover demand is vital.

Following Belgium, in 1976, Honda decided to locally produce the CB125S in Italy. At the time, the market for the small-size motorcycles in Italy was growing at a rate exceeding that of large motorcycles. Honda boasted an overwhelming share of the large motorcycle market, but imports of small-displacement motorcycles were effectively banned, making it impossible to enter the market at the time.

Therefore, Honda signed a joint venture agreement with local capital that included technical assistance and 50% equity participation to establish IAP Industriale, but the company had a difficult start, suffering from the seizure of imported parts and the suspension of benefits from the local development fund. The company scraped together the few permitted imported parts and finally assembled the CB125S, but it fell into the negative spiral of no sales, no profit, and no cash flow, with plant operations falling to 10 units per day and annual production of 2,500 units.

Business restructuring measures were explored, but the joint venture partners were unable to reach an agreement and forced to dissolve the alliance. Honda purchased 100% of IAP shares, and established Honda Italia Industriale (HII) in 1981. This time, with the lessons learned from IAP, the development of a new model was carried out at Honda R&D based on in-depth market research, resulting in successful production at a high local content rate in cooperation with local parts suppliers. Two years later, in 1983, HII was able to recover, recording production of 120 units per day and 27,000 units per year.

CB125S

NSR125 production line at HII's Atessa plant (1988). The NSR125 was also exported to Japan.

MHSA production line (1987)

MHSA production line (1987)

In Spain, the journey to building local production was challenging right from the beginning. Since the import of complete motorcycles made in Japan was prohibited, Honda entered into a 10-year technical cooperation agreement with a local manufacturer, Serveta, in the late 1960s, entrusting the assembly and sales of BH's mopeds and exploring opportunities to make a full-scale entry into the Spanish market.

When the contract with Serveta expired in 1980, Honda established Honda España with local companies C. de Salamanca and Tronc.

Honda España strived to expand its sales channels by importing knock-down kits of 125 cc motorcycles model produced in Italy and 450 cc model produced in Brazil, in addition to mopeds produced by BH.

This, however, led to a backlash from local manufacturers. Honda was unfairly suspected of bringing in parts that were not made in the EC, and a lawsuit was filed by the government authorities. Behind this was the desire of the Spanish industry and authorities to protect their country's motorcycle industry, which once boasted an international position particularly in off-road motorcycles. From this experience, Honda learned a valuable lesson: cooperation with local companies is essential for doing business in Spain. In 1982, Honda formed a partnership with Montesa, a traditional local motorcycle manufacturer, and established a 50-50 joint venture, Montesa Honda S.A. (MHSA). While supporting Montesa, which was in financial difficulties, MHSA obtained permission for a joint venture motorcycle production business and finally launched the SH75 scooter, in 1986, which became a hit in Spain.

The difficulties leading up to this point were extraordinary, with endless misunderstandings stemming from cultural and customs differences. For example, if someone dropped an object and it broke, it was typically explained that the object fell and broke. When asked “how much?” the typical response would be a vague one like, “Almost.” There was even a union dispute over whether workers would go bald by being required to wear a cap. However, people involved in manufacturing are sure to find common ground somewhere. The importance of facing issues with sincerity, honesty, straightforwardness and patience became widespread at HMSA. Developed under such corporate culture, the SH75 gradually became popular in Barcelona and throughout Spain. It was also well received in Italy, and MHSA was suddenly infused with energy. Combined with World Grand Prix popularity, the Spanish motorcycle market was booming again, and MHSA grew to become the largest motorcycle manufacturer in Spain.

Honda carefully cultivated motorcycle demand in Europe by strengthening operations of its local subsidiaries in accordance with the circumstances and market conditions of each country, and by building close relationships with local industries and people. Eventually, HII and MHSA, along with BH, served as a motorcycle supply hub for Europe.

MHSA’s hit SH75, which was well received not only in Spain but also in Italy.