Honda EV Plus: The Dream of an Electric Vehicle / 1988

"It all began with a debate concerning the feasibility of solar power."

"An electric vehicle (EV) running on solar power?" thought Junichi Araki, LPL of the first-generation EV basic research team. "Maybe the time is right for alternative fuel cars to be running all over town." He had just read a magazine article describing the exploits of the General Motors Sun Racer, the solar car that had taken the first place at the inaugural World Solar Challenge (WSC) race held in Australia in November 1987.

Honda EV Plus cruises the streets of America. This advanced electric car offers the dynamic performance of a gasoline-powered car, along with all the comforts one expects of a Honda.

Several managers in charge of research at Honda R&D Center had recently held a meeting, in which they debated the types of research that they should conduct for the coming 21st century. The meeting was an important one, since their target was to be an age of "clean energy." They were well aware that they were working well in advance of the time when the world's available petroleum reserves would dry up, so all those in attendance shared Araki's sentiments about alternative energy vehicles.

Several issues were discussed during the meeting. However, overall the participants were mindful of the fact that electric vehicles had fewer parts than conventional vehicles, and this prompted them to look into the possibility that their EV (electric vehicle) could be an automobile easily manufactured anywhere in the world. The meeting also led them to reconfirm the necessity of enhancing technology with regard to the internal combustion engine, such as improving gas mileage and reducing emissions. Therefore, they would dedicate their future product deve-lopment efforts to the protection of the environment.

"Electric operation was the most likely candidate, in terms of alternative power," Araki recalled. "However, Honda had no previous experience with electric powerplants. Also, at the time not much research was being done with regard to alternative-fuel vehicles. Therefore, we decided to take up the challenge of making an electric vehicle. We also considered participating in the WSC, simply because we knew the harsh conditions of such a race would enable us to produce our technology even more quickly."

The research and development of electric vehicles got under way at Honda in April 1988, through basic debates like this one. It started out fairly small, with a staff of only four, however, basic research was now under way.

A Corporate Project Involving Scores of People

It was soon apparent, though, that several companies in Japan and overseas had already commercialized the concept of an electric vehicle. For this, the staff at Honda had the first and second oil crises to thank. In fact, Honda was the last to join the race.

Accordingly, the members argued that, as Araki put it:

"Other companies that had worked for so long with electric vehicles would probably continue developments based on what they already had accomplished. However, we had to make use of the very best cutting-edge technology to begin our development."

The truth in such a statement was evidenced by the fact that Japan was rich in automotive and electronics technologies. It was a great source of pride for the Japanese, and the envy of nations the world over.

Electric operation was at the time only associated with golf carts and amusement park rides. When compared to the amount of energy displaced by gasoline combustion, the amount of energy displacement from a battery was lower by two digits. Since it took many hours to recharge a battery, it was very inconvenient to use such a system in most applications. To make matters worse, no team member at the R&D Center had any experience in EV-related technology. Therefore, it would be impossible to discuss its technology with manufacturers of various components.

The motor and battery system remained the biggest components in an electric car. However, the motor was entirely different from that found in a conventional car. At the time, there was no motor compact enough yet high enough in output or efficiency to be loaded into an electric vehicle.

The battery type was another question, since the only type available for use as the car's chief energy source was the lead-acid unit. Upon hearing a spokesman from a manufacturer of electric vehicles say that at least four years were needed to develop a new, next-generation battery, the project members were shocked. They were discovering the truth in their assumption about development in the electrochemistry field: everything would require a great deal of time.

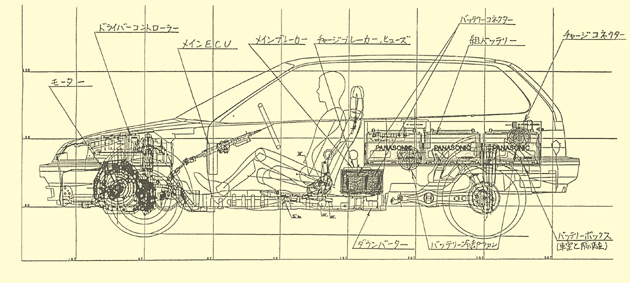

Layout plan of the first electric vehicle made by about 100 members from throughout Honda. It was based on the three-door Civic. The shame and regret the members experienced at the LPL's outrage after seeing this vehicle became the motivating force behind ideas and inventions for the future development of electric vehicles.

"However, we have to start somewhere," they thought, as they worked to assemble an electric vehicle from the skeleton of a CR-X. The vehicle was made lighter by using aluminum for the body and acrylic instead of glass. This was the birth of EV "number one."

A meeting of top management was held at Honda R&D in October 1990 regarding Honda's entire range of motorcycles, automobiles, and power products. It was a meeting to debate the direction that R&D should take for the last decade of the 20th century. Information on several themes was gathered and debated, including, of course, those relating to electric vehicles, for which a project had been started two years earlier. Takefumi Hiramatsu, the Research Administrative Director (RAD) of a development project for the commercialization of electric vehicles, was in attendance at the meeting. "It was at that meeting that I was again convinced to continue the full-scale development of electric vehicles," he recalled.

The meeting had also impressed upon Hiramatsu that several outside factors were enhancing the significance of development in electric vehicles. There was, for example, a move in the U.S. toward more stringent enforcement of emissions controls. Concern had grown during the latter half of the 1980s concerning the effectiveness of the 1970 Clean Air Act instituted in late December 1970. The public mood had shifted toward revising the Clean Air Act, including the addition of regulations adopted in the state of California by CARB (California Air Resources Board). Moreover, beginning in the 1990s, the U.S. began importing more oil than it produced. Thus, the movement toward new regulations was made from the standpoint of national defense, as well as for reasons of economics.

"These were signs of a future I saw spreading throughout the world," recalled Hiramatsu. "Therefore, in keeping with the big changes in social values, I felt that in addition to making technical improvements I wanted to develop something that would replace the technology that had been the very heart of Honda."

The ZEV (Zero Emission Vehicle)*1 regulation was issued in November 1990 in the U.S. as a law that would encompass the CARB regulations established two months earlier. It was to take effect in 1998. In the face of these developments in mind, early in 1991 Honda made the development of electric vehicles a major strategy. In order to begin full-scale development, some 100 employees whose collective expertise covered a variety of areas, gathered from Honda R&D's Wako Center, Tochigi Center, HGA and what was then the Asaka Kita Center. This was to be their project.

Note:

*1 ZEV (Zero Emission Vehicle) Regulatory Act: A law requiring automakers with sales in California to sell a set number of electric vehicles (Initially 2 percent of the total number of car sales.)

"Why don't you just dig a hole, and bury it!"

Although the project was launched on a broad scale, the team was thrown together quite hastily. As a result, most of the team members had no knowledge of electric vehicles. As could be expected, the group lacked a sense of purpose and unity.

"The members were not easily united," said Kenzo Suzuki, Project Leader (PL) in charge of the testing of electric vehicle powerplants. "We wondered how we were going to come up with a united idea for an automobile, especially given the limited technology we had available to us at that time."

The first prototype to be test-manufactured as a significant project was based on the Civic three-door model. In a race against time the car was manufactured using a commercially available motor and battery obtained from the market. For most team members, it was their first attempt at building an electric vehicle and was thus a matter of "labor pains." However, in July 1991, with the team members assembled to watch, the car made its first run without any problem.

"What do you know; it runs okay," the team members said with obvious relief. However, Araki, the Large Project Leader (LPL), turned beet-red with anger.

"Before I knew it," recalled Araki with a chuckle, "I was yelling, 'You call this a car? What the heck did you just make? Why don't you just dig a hole, and bury it!'"

Araki then spent about two hours explaining the reason for his outrage, saying that at first glance it was obvious that the car was "a compromise; an excuse for having had no previous experience."

"As long as we continue trying a variety of measures in a project, each car we produce must constitute a learning experience that leads to the next step," Araki said. "If a car doesn't lead to greater experience, we might as well not build it. I was so disappointed that they hadn't put more passion into the project."

The team members were deeply shamed and mortified. The experience, however, became a driving force for coming up with new ideas and inventions. Shigeru Suzuki, the PL in charge of powerplant design, said, "After being questioned, 'Why didn't you change the battery specifications to better meet the needs of an electric vehicle?,' we reexamined the issue many times. However, because of that, we were able to propose a battery format and size that could be better used in an electric vehicle. Therefore, the battery manufacturers approved our proposal, and it became a world standard."

There still was time before the ZEV Act was to be enforced. Honda's new goal in developing electric vehicles had become "to make a good electric vehicle, with no compromises."

Finally, Development Begins: Producing the World's Finest EV

The new essential technologies*1 required for electric vehicles were mastered one at a time through the process of research and development. In particular, the motor and control devices were of critical importance. Together they comprised the equivalent of an engine in a gasoline-powered vehicle. Honda decided to pursue the in-house manufacture of these parts. However, knowing that the ideal motor for an electric vehicle would be one that operated most efficiently, Honda's project team employed the DC brushless motor. This was at the time an unusual choice for a large motor.

"It was simply the most efficient, from the standpoint of test simulations," recalled Shigeru Suzuki. "Honda concentrated on this motor, and through intensive effort we increased its efficiency."

Despite lingering concerns that it was an unusual choice, the first motor Honda engineers put together performed at a level that exceeded their expectations. The motor then went through several years of trial and error testing until it was completed as an electric-vehicle motor. Competitors in the Japanese market who were then using several different types of motors also turned to this same type of motor. It was an unexpected move by Honda's competitors that proved the company had made the right choice.

It had so far been determined that most essential technologies had been mastered. Thus, in June 1992, D stage (production oriented) development began on electric vehicles. Top management ordered that this completely new type of vehicle be "the finest EV in the world"; that it "express a clean, quiet, smooth ride that is of another dimension"; and that it be "advanced."

Note:

*1 Factoring technologies are individual technologies and systems needed to establish a new technology or system. In the case of the EV, they are as follows:

a) New technologies and systems due to the changing nature of the power motor:

* Drive motor

* Battery (second battery)

* Motor controller

* Air-conditioning system

* Electric power-assisted power steering

* 12-volt battery recharger

* Brake system

* Regenerative control system

* Total-control system

b) Meeting legal requirements

* Impact safety performance (meeting needs caused by increased weight)

* Defroster performance

c) Additional technologies

* Recharging system

* Electric safety system

* Heating system

* Measures against electric field (electromagnetic waves)

Test Drives Totaling 130,000 Kilometers

Even at the start of development, the only EV that could be driven on a public road as a test vehicle was a conversion model of the Civic Shuttle. It had a driving distance of between 40 and 50 kilometers, rendering it highly impractical for most applications. Furthermore, no solution was in sight for sufficient impact protection, since the battery's added weight had to be offset by weight savings elsewhere.

Hiramatsu and Araki, who became manager of automobile research after the EV project advanced to the D stage development phase, had meanwhile become involved in a campaign aimed at educating project members and other R&D members about the importance of developing electric vehicles. The campaign was prompted because a majority of them had voiced their concerns through such statements as "Electric vehicles can't make money because they're expensive, heavy and don't even run," and "Petroleum won't dry up." In addition, F-1 racing activities had been suspended for a second time the end of that year, raising yet another question: "Why electric vehicles now?"

The campaign to promote an understanding of environmental issues paid off in time, proving the value of a success first achieved at Honda's R&D Center, and then spread throughout the company. The campaign helped greatly in the promotion of Honda's future operations.

In the U.S, Honda had dispatched several teams of associates to major electronic manufacturers. These individuals were to search for any technology they could use, and to determine the actual state of the current knowledge. The U.S. was also examined as a possible site for production of the EV. This was because the electric vehicle was a car that could not exist unless new technologies - meaning ones that did not exist in the realm of conventional automobiles - were brought into the mix.

It was in such an environment that the EV-X was produced, under the research theme of being the "finest EV in the world." The car was to be exhibited at the 1993 Tokyo Motor Show. Yet, despite the fact that it was indeed a "show car," it was one that actually ran. Moreover, the CUV-4 had also been produced by converting Civics in order to collect actual market data. A two-year test drives began in 1994, following the signing of a contract with a California power company.

The CUV-4, one of the EV test cars driven for a total of 80,000 miles (130,000 kilometers) in California. The data gathered from such tests contributed to the development of the Honda EV Plus.

"Honda has a very big presence in the U.S.," said Kenji Matsumoto, LPL of the company's development project. "And in terms of market share in individual states, Honda ranks first in California. If people were troubled by the legal regulations, we felt Honda should assist them."

Thus, at the switchover point from research to development, it was determined that California would be the main market for electric vehicles, with an annual production plan of about 300 units.

However, before the car was to be taken out on an actual test, there was a need to perfect the car's electric safety measures. Repeated tests were conducted in order to secure the same level of safety as a gasoline car would provide in a collision. For example, a load of force several dozen times greater than the highest possible level that could be generated in nature was forcibly applied to the battery and other parts.

"After making some alternations in the hardware specifications*1 and meeting all legal requirements in Japan and the U.S.," recalled Matsumoto, "we took the EV out for a test drive."

An added issue was raised during the test, however. Unlike the situation during the simulated test, the vehicle's lead-acid battery was found to deteriorate very quickly when left in the heat of summer for a week or two. It became evident that the way people handled their cars varied greatly. It also became evident that there was a need to switch batteries to stress-resistant, nickel-metal hydride (Ni-MH). This was a new type currently under development, and was being "co-created" with an electric manufacturer.

"Although we had managed to achieve some understanding of the practical application of Ni-MH batteries, the real work had just begun," Hiramatsu recalled. "Batteries are a fusion of chemical reactions, science, and engineering. Therefore, there was an element of invention inherent in the development process."

Nearly two years were spent in actual test drives in the U.S. A total of ten cars, including monitor cars from HRA and AH, were used in the tests, which together accounted for 80,000 miles (130,000Km) in driving distance. Then, as a result of all that hard work, the EV's basic structure was finally established.

Note:

*1 Certain alterations were made to the hardware specifications, including the following:

a) Total voltage: from 240 volts to 288 volts

b) Motor: from 40 kW to 49 kW

c) Transmission: reducing the speed of torque-converterless 3-AT at a fixed speed rate.

d) Battery: from lead-acid battery to nickel-hydrogen battery

First Prototype Gets the Green Light

Project members flew to the U.S. while the actual test drives were being conducted, in order to conduct direct interviews with prospective customers. Such an undertaking provided the team members an opportunity to meet with many Americans, who from a social context had a deep understanding of the need for environmental preservation.

"These were people who empathized with and applauded Honda's commitment to the environment as expressed through electric vehicles," Matsumoto said. "The fact that such people existed gave us so much courage. Really, you can't imagine how much. I'll always remember the words of one of them: 'This car is right for me. I'm doing the right thing.'"

The first prototype EV was completed in December 1995, reflecting the vast amounts of data obtained through research results, drive tests, and interviews.

"We wracked our brains coming with a body design that said this was an electric vehicle," Matsumoto recalled. "All we had in mind was to create an EV with an original body rather than some conversion of an existing model. We had put too much of our energy into the car for that. Also, we believed that if we were to announce its arrival as a conversion, top management would yell at us, saying, 'Get serious!,' and give us a kick...."

The cost of creating an original car body can be quite high, however. Moreover, electric vehicles were to be made on the condition that they could be produced in small quantities. The Development and Engineering divisions worked as a unified force in that respect, ascertaining the machine's engineering feasibility and ensuring its high quality. Permanent dies were employed for large parts for the first lot of prototypes. In this way, a motor manufactured at EG and a body manufactured at Tochigi Factory (TA)'s Takanezawa Plant were put together to become the EV, representing the thorough capabilities of Honda's technology.

In January 1996, then-President Nobuhiko Kawamoto test-drove the newly minted Honda EV. "It's a 'go'," he said to the project members. "Let's do it."

"When it's complete, introduce it immediately," said Hiroyuki Yoshino, then the executive vice-president. "Introduce it simultaneously in Japan and the U.S."

Yoshino's words were more than an encouragement. They were an order.

There was no time to lose, and accordingly the project members split into two groups: one in Japan and another in the U.S. This would allow them to enhance their electric vehicle even further. Then, in April 1996, the result of that effort was announced simultaneously in Japan and the United States.

Anticipating the Age of the EV

The Honda EV Plus rolled off the production line at Takanezawa Plant in April 1997. The production ceremony was unusually exciting, given that it was just a single car. Reporters and camera crews from five TV stations and ten newspapers were there to capture the moment. As a decorative paper ball burst open to release ribbons and confetti on the car driven by a Honda employee, the cameras and lights went into action, recording the scene for posterity.

At the line-off ceremony to celebrate the first Honda EV Plus at Takanezawa Plant in April 1997. The vehicle gained national attention, with teams from five TV stations and ten newspapers covering the event.

Matsumoto, who had put together the Honda EV Plus and taken it to market, was already aiming toward further technical advancement in the field of electric vehicles.

"There still are many issues at hand, including the battery," Matsumoto said. "On the other hand, there are increasing numbers of people who are willing to contribute to the preservation of the global environment. For example, people put solar batteries on their roofs without worrying about the expense. School children are being educated on environmental issues today, more than ever before. When their generation ages to the point that they will be able to buy cars - say, in five to ten years - those cars will have to come with standard environmental and safety equipment. I can definitely sense the coming age of the EV.