Returning to the World Motorcycle Grand Prix / 1979

Speeding Through the 1960s

In 1959, five years after announcing its March 1954 entry in the Isle of Man TT Race, Honda began its all-out effort to achieve glory on the racing circuit. Surprisingly, it took Honda only a few years to reach the summit on that journey. Supporting this rapid advance were innumerable technical innovations, including the multi-cylinder engine and cam-driven geartrain.

The British GP held at the Silverstone Circuit on August 12, 1979. Because the NR500's engines were not quick to start, they had to fight a difficult battle right from the beginning. Push-starting was the only alternative.

Honda successfully avoided the mid-1960s trend toward 2-stroke engines. In fact, once it had made DOHC 4-cylinder engine technology an industry standard, Honda went on to make the six-cylinder DOHC powerplant a reality with its RC166 250-cc and RC174 350-cc machines. Boasting a mechanism lauded for its "clockwork precision," the new high-revolution, high-output engine outperformed its rivals, leaving behind a trademark exhaust note that fans soon popularized as "Honda Music."

The year 1966 was one in which Honda became the first manufacturer in the history of the World Motorcycle Grand Prix (World GP) to win all five classes of the series. Deciding that its original goal had been met, Honda then withdrew from the World GP circuit in 1967.

Just like the racing machines it created, Honda ran through the 1960s with great speed, transforming itself from a manufacturer from the small island nation of Japan into the world's top name in motorcycles. Thus, Honda closed the book on its World GP story, with numerous victories in hand.

After a Decade, a Comeback to the Grand Prix

Following its withdrawal from GP racing in 1967, Honda began to focus its energies on the development of mass-production automobiles. The insatiable appetite for power and speed that Honda had developed through racing gradually changed to a focus on economy and environmental responsibility through the pursuit of technologies that would enhance fuel efficiency and lower pollution. In 1973, Honda introduced the new CVCC-equipped Civic model, becoming the first carmaker to offer a model in full compliance with the U.S. Clean Air Act passed by the U.S. Congress.

In the area of development, Honda was attracting the world's attention with a wide range of original technologies. Honda's motorcycles had a different story to tell, however. The number of motorcycle development personnel had been reduced to around one-third the level of the early 1960s, with the remaining two-thirds transferred to the Automobile Division. Yet, despite the dwindling staff, Honda was able to release a series of highly successful models, including the Dream CB750 Four introduced in 1969, and the Benly CB90 and Dream SL250S in 1972. However, even after 1973 - the year Honda established the Asaka R&D Center (HGA) as its new key facility for motorcycle development - the company's basic motorcycle technologies remained unchanged from the 1960s. Of course, the reduction in development personnel had played a part in this, but the major reason for such stagnation was Honda's withdrawal from racing. It was a move that had robbed the company of its ability to test new technologies.

A sense of crisis soon loomed over the skies at Honda. If the situation were allowed to continue, the company would be left behind in terms of technology, a field in which it had led the world. To foster young, world-class talents and develop innovative motorcycle technologies, in November 1977 Honda announced that it would return to the Grand Prix. The goal was to enter the World GP in 1979 via the 500-cc class, which was the premier category in the series.

Organizing the NR Block: Preparing for a Comeback

Several days after Honda's comeback announcement, Koichi Yanase, manager of Suzuka Factory's First Engineering Work Section, received an unofficial order of transfer to HGA.

"Four section managers, including myself, were called by Mr. Takayuki Kobayashi (then general manager of Suzuka Factory) for a short chat," Yanase said. "I was asked where my birthplace was, and I remember answering 'Tokyo.'"

Yanase reported to his new post on December 10, whereupon he was told by Yuhei Chijiiwa, the general manager of HGA, that he was to manage the Motorcycle Racing Department. He was also handed a portion of a document outlining the company's plan for racing activities. That plan described a project with three basic targets:

[1] Create innovative technology through racing activity.

[2] Foster young talents who can become key leaders in Honda's future.

[3] Become world champion within three years.

Other than a yearly budget of around 3 billion yen and 100 or so available personnel, the details of the project, including its name, were as yet undecided.

"The project name was selected as NR (New Racing), based on my suggestion," Yanase said. "That was virtually our first challenge, since we couldn't ask for help from the people who had experienced the World GP during the 1960s. So, actually we were expecting the road ahead to be very difficult."

January 1978 saw the start of preparations for Honda's comeback in motorcycle racing. Those preparations got a significant boost when Yanase was introduced by Nobuhiko Kawamoto (then corporate director of Honda R&D) to Takeo Fukui (chief research engineer in the First Research Block at the Wako R&D Center), who was subsequently assigned to the project as manager of the Engine Performance Group.

Fukui immediately undertook a study of the new engine with Shoichiro Irimajiri, Honda R&D's corporate director, who was then to serve as general manager of the NR project. Concurrently, Yanase was busy gathering the human resources needed to form the NR project team. Visiting Honda factories in Suzuka, Hamamatsu, and Saitama, Yanase assembled over seventy people in a little over two months.

The project was officially launched at HGA in February 1978. By the time the NR Block was formed in April, the team had grown into a group of nearly 100 staff members, some of whom were recent college graduates.

Coming Back with a 4-Stroke Powerplant

The first step toward Honda's World GP comeback was to determine the specifications for the machine they would create to achieve that goal.

Therefore, immediately after his transfer to HGA, Fukui began studying data from past World GP races. In 1977, the official regulations of the World GP specified a machine having four cylinders and six speeds. However, the majority of machines competing in the GP employed 2-stroke engines. It was to turn out that the World GP would be dominated by 2-stroke engines that year. Before 1977, the entries often included 4-stroke motorcycles, some of which even won their races. Accordingly, the data showed that there was no significant gap between the 2-stroke engine and its 4-stroke cousin.

The 2-stroke engine could no doubt generate power more easily than the 4-stroke. Moreover, its simplistic structure, which was free of camshafts and intake/exhaust valves, made the 2-stroke assembly as much as 20 kg lighter than a 4-stroke engine. The drawback was poor fuel economy, but that did not really matter, since GP racing essentially involved a sprint over a distance of approximately 100 kilometers.

However, the Honda team wanted to fight for the World GP title using machines carrying 4-stroke engines. They wanted to live up to the expectations of their company, a former champion that had taken 4-stroke technology to the summit of motorcycle competition. Often described as having "clockwork precision," the 4-stroke multicylinder engines, so brimming with technology, were a Honda trademark.

Therefore, it was not a matter of the Honda development team being so interested in running against the grain. Instead, their desire to win with a 4-stroke engine was simply a statement of what they knew to be true. The 4-stroke, multicylinder design was a winner.

So it was that Honda's return to the World GP using 4-stroke powerplants became a battle. It would be a contest of wills-a statement of honor-in which the company would put its most fundamental convictions to the test.

The Oval Piston: Heart of a New and Different Breed

To design a 4-stroke, 4-cylinder engine in the conventional manner would not produce a machine that could out perform its 2-stroke rivals. No, for a 4-stroke engine to generate the same level of output as a 2-stroke engine it had to have twice as many cylinders as its competitor. Moreover, 20,000 r.p.m. was the absolute minimum a 4-stroke engine required to produce superior horsepower.

Increased power meant that the 4-stroke engine would have to consume and exhaust more of the critical fuel-air mixture. In other words, the aperture of the valve would have to increase for enhanced intake and exhaust efficiencies. To do that, the number of valves would increase, also. However, conventional circular pistons would accommodate only four or five valves. Furthermore, such a structure would provide no technical advancements, as compared to the time when Honda was competing in the World GP with its 4-valve DOHC engines. Therefore, the NR project's new challenge was to achieve "innovative technology," being more than a mere refinement of the previous technology.

Winning is the essence of racing. Thus, in winning the race, the team could prove that its technology was superior. Hence, there was no significance in creating a machine that was not capable of winning. That would lead neither to technical progress nor to the fostering of outstanding new talent. However, the Honda NR development team knew that to make a comeback in the World GP meant the establishment of a training ground for young talents; people who would strive to improve their skills through the creation of truly great motorcycles. If there were no chance of winning the race or fostering talent, Honda would be better off not trying at all.

Honda's answer was the adoption of an oval-piston design. With eight valves lined up atop the pistons, each supported by two connecting rods, the team's new 4-cylinder engine looked like an 8-cylinder. According to Fukui's calculation, the engine could potentially reach a maximum speed of 23,000 rpm and output of 130 horsepower. Therefore, the target output was set accordingly, at 130 horsepower.

However, the oval-piston design necessitated an extremely difficult manufacturing process, in which machining accuracy would be more critical than ever. Of course, no such design had been adapted for use in a high-performance racing machine. Nevertheless, the spirit of Honda was never to be pessimistic, and the team decided it was worth trying as long as there was a real possibility. In making such a decision the team was well aware of the difficult path ahead. In order to beat 2-stroke engines, they had to transcend common-sense thinking and bring in daring new technologies.

The concept for Honda's new engine was finalized in April 1979, and the NR Block set as its primary goal the realization of an oval-piston engine.

From Fantasy to Reality: Completion of the 0X Engine

The team faced difficulties right from the start. In fact, they had to prove that oval pistons, cylinders, and piston rings could actually be made. They also had to find a manufacturer that could help them do it.

Finally, the team commissioned the production to an associate company, Honda Metal Technology, located in the city of Kawagoe, Saitama Prefecture. Development went forward there, but the process was not entirely free of problems.

Since in an oval piston a semicircular curve has to merge into a straight line, continuous curvature could not be maintained and edges were created along the piston. This made machining very difficult. Similar problems were found in the honing of the cylinder's inner diameter, and many hours were spent in production.

The team members in charge of engine design had their own private concerns, but spirits were high in the NR Block, where team personnel worked eagerly to prove that their engine was more than a fantasy.

In July 1978, three months after the start of production, the NR team finally completed a dual-valve head, 125-cc single-cylinder engine prototype, which they named "K00." Contrary to the team's concerns, the engine turned properly on the bench tester. With renewed confidence, the NR Block continued its efforts and the following October completed an eight-valve head, water-cooled, single-cylinder engine, the "K0." Each day was spent making a prototype, testing it, modifying the specifications, and testing it again. Repeated testing revealed that the oval-piston design would cause problems at speeds in excess of 10,000 rpm, due to poor machining accuracy and the loss of durability. Regardless, the team members knew they could not continue testing single-cylinder engines indefinitely.

The NR Block was in fact developing a 4-cylinder engine commensurate with the testing of single-cylinder units. In April 1979, they completed a 4-cylinder V-engine called the "0X," which was to become the heart of the NR500. During the bench test, the engine produced 90 horsepower, making it clear that they had not yet reached their target of 130 horsepower.

The NR Block had also formed a new materials group in order to study two key problems - machining accuracy and durability. The group leader was to be Yoshitoshi Hagiwara, then chief research engineer in HGA's Third Research Block, who had been collaborating with the development team since the early stages of development. One of the group's key responsibilities was to collect the engine parts broken during testing and investigate their causes of failure. It was a tedious task in which it was often necessary to go through the pieces of several parts one by one and divide them into rings, valves and so forth. The group even studied new materials such as carbon and complex high-tech materials, along with enhanced manufacturing techniques that might be used to build parts which could withstand high engine revolutions. Ultimately, these efforts were fruitful, producing notable improvements in durability.

The Unconventional: Adopting a "Shrimp Shell" Frame

It was not just the engine that was unconventional. To increase its competitiveness, the NR500 also employed a frame technology that was simply unheard of in the conventional realm of engineering.

Tadashi Kamiya, a research engineer in HGA's Third Research Block who had joined the NR program in the summer of 1978 as chief of the test group for completed product, proposed several ideas that he was thinking could be adapted for use in production cars. One of them was an aluminum frame called the "shrimp shell."

The shrimp shell, which integrated a monocoque structure with the cowling to form the frame and body, virtually encased the engine, which was then inserted through the rear like a cassette. The engine was fixed with 18 six-millimeter bolts inserted at both sides. Although the panel was paper-thin at just 1 mm, once the engine was in place the frame was able to ensure the required rigidity. Additionally, the frame weighed just 5 kg, which was about half the weight of an ordinary tubular steel frame.

The idea, not surprisingly, encountered outright confusion among the members of the NR Block. In order to convince his colleagues Kamiya created a prototype model and, the members understood the concept of his shrimp-shell frame.

The second idea involved the wheel. Kamiya thought of adopting a 16-inch wheel instead of the mainstream 18-inch wheel.

"By reducing the tire diameter," Kamiya said, "we could reduce the machine's weight by around 4 kg and vehicle height by around 5 cm. The lower air resistance and smaller disc diameter also contributed to a lower moment of inertia, enabling the machine to accelerate faster. Moreover, the reduced frontal projection had the effect of increasing output by several horsepower.

"When I compared the 18-inch wheel with the 16-inch wheel, I asked myself which of the two would cross the finish line first in actual races, where average speeds often exceeded 200 km per hour, I was convinced that the 16-inch wheel had greater potential, not simply from the standpoint of partial speeds at corners but by putting all the elements in proper perspective."

Kamiya also adopted a vertical standing screen to be attached to the cowling, instead of the regular semispherical type.

"You could call it an invisible cowling," he said. "With this design we can still achieve sufficient aerodynamic effect. Since the wind is directed upward after hitting the screen, the rider is subjected to less wind resistance at high speeds. Also, the area of frontal projection becomes smaller."

Another idea involved the swingarm and drive sprocket, which were positioned along the same axis. Because chain length was no longer affected by the upward or downward movement of the swingarm, there was no need to provide extra play. This meant an advantage in reducing shock due to acceleration or deceleration, thus stabilizing the suspension's performance over an entire course.

Kamiya believed that no 4-stroke engine, regardless of its merits, could win with a frame design based on conventional thinking. Thus, the NR's frame was constructed from the standpoint of minimizing volume and weight. The staff sought to create a 125 cc frame capable of carrying a 500 cc engine. These were just examples of the many unconventional, even outrageous, ideas being implemented in the new machine. However, they were all based on strategies that had been calculated to an absolutely meticulous degree.

The NR500 was put to the first test ride in Yatabe, Ibaragki Prefecture, in May 1979. Although the road test brought up problems that the team had failed to identify in bench testing, these were gradually resolved through refinement of the engine in repeated tests at Suzuka Circuit and on the course at Tochigi. The NR500 became more complete with each passing day, and soon it would be ready for its first World GP event. Due to a significant delay in the NR500's overall development schedule, though, its comeback had to be pushed back to the British Grand Prix, which was to be held at Silverstone on August 12.

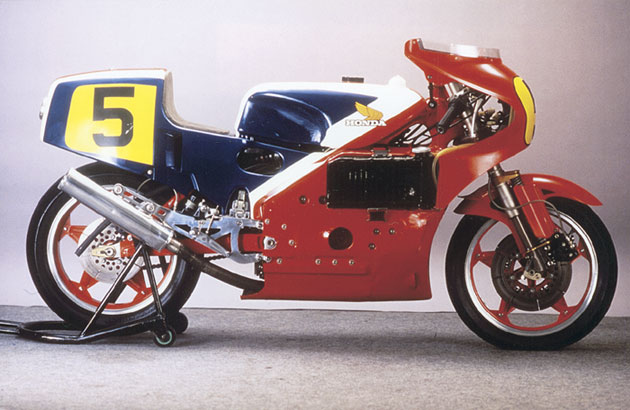

The NR500 was at last completed in July 1979. Equipped with a 4-cylinder V-engine and 100-degree cylinder banks, the machine had a maximum output of 100 ps at 16,000 r.p.m.

The NR500 evolved as a machine designed to claim the summit of motorcycle racing. It incorporated numerous original technologies, including the oval piston engine and 'shrimp shell' frame.

The NR500s: A Humiliating Debut

The NR team had finally made it to England, where the machines were receiving their final tuneups in preparation for the GP race. At the same time, Yanase was making various arrangements in order that the team might concentrate on the race free of hindrances. Thus, in addition to setting up the bikes for optimal performance on the track, there were many other things that had to be done for each race, such as arranging transportation and accommodations for the many staff members involved. The World GP, often referred to as the Continental Circus, had most of its races in Europe. Therefore, while it was possible to develop the motorcycles in Japan, it was impossible to manage the races from Japan. The distance was simply too great.

Yanase rented a warehouse in Slough, an English town near Heathrow International Airport, as their team's base of operations in Europe, while in Britain additional preparations were underway through a company called HIRCO (Honda International Racing Corporation). Honda had established HIRCO in December 1978 as a joint venture with Honda UK for the management of all racing activities, including competition in the World GP series.

Honda's riders for the 1979 season would be Mick Grant and Takazumi Katayama, the latter having competed in the 1977 World GP series as a privateer, where he ultimately won the championship title in the 350-cc class.

For their part, the NR500s kindled great expectations upon their appearance at Silverstone, portending awesome performance with their original engine design and sleek styling. However, those expectations were mercilessly shattered in the qualifying round. These bikes, which were still in development, barely performed well enough to get through to the final. Even then, Grant fell at the first corner following the start and quickly retired. Katayama also retired after several laps due to ignition problems.

Though they had not expected a win in their very first race, the NR team was deeply disappointed with the outcome of their efforts. The NR500s were brought back to Japan, and improvements were made to further reduce weight and increase output. However, those really were not the fundamental solutions that the project team had long sought.

Harsher realities awaited in the French GP, the twelfth race of the 1979 season where both machines failed to qualify for the final, meaning that no results whatsoever could be garnered from their presence. However, the team could not go back to Japan without data, after having spent so much time and money in preparation for the French event.

Therefore, the staff of the NR Block flew to England, and with help from HIRCO tested the NR500s at Donington Park. The test was a fruitful one, in which new areas of possible improvement were identified. However, there was no improvement in speed, and the machines were still running two seconds behind the lap record. In the world of racing, where one-hundredth of a second determines the winner, two seconds was just too great a handicap.

Refining the Engine - a Top Priority

Having finished the 1979 season with disappointing results, the NR500s had two major problems that were considered unique to 4-stroke engines.

First, was the factor of extreme engine braking. When development began, the team viewed engine braking as an advantage, believing it would assist in overall control of the bike. On the contrary, the engine braking caused the rear wheel to hop. To counteract it, the team developed a back-torque limiter with a built-in, one-way clutch so that the wheel would spin when the force applied to the wheel exceeded a certain level. This methodology was later incorporated in the VF750F, making it the first production bike to be equipped with a back-torque limiter.

Acceleration was the second problem. It simply did not provide the necessary subtlety of control. The ability of the engine to generate ample low-end torque - a characteristic of 4-stroke engines - also made cornering control difficult, resulting in the loss of time. During the 1980 season the team experimented with throttle pulleys based on various shapes, but as yet there was no solution.

Weight was another area in need of attention. Although the first 0X engine was lighter than the average 2-stroke engine, weight gradually increased as durability improved. Before long, the engine had put on as much as 20 kg. The development team conducted an exhaustive review of materials, going to titanium and magnesium in order to achieve weight reduction. However, the new material combination was quickly copied by rival teams, leaving Honda with no advantage in that area.

The shrimp-shell frame, which had so greatly contributed to weight reduction, also had a drawback. Because of its cassette-type mounting structure, the engine had to be removed from the frame in order to perform maintenance. This made it difficult for the engineers to achieve optimal settings within the limited time allowed in the qualifying runs. Accordingly, the team decided to adopt a pipe frame to the machines, beginning in 1980. At the same time, the wheel size was changed to 18 inches.

Ultimately, the problem with the NR500 was that so many new technologies had been introduced that its potential for completion had been compromised. Realizing this, the NR Block prioritized problem areas, placing the top priority on refining the engine. This, they believed, was the most fundamental problem of the bike.

The NR500 was refined through a long series of tests at Suzuka Circuit. The rider in the photo is Takazumi Katayama (January 1980).

The new and greatly improved NR500s competed in an international race held in Italy. Although it was not a World GP race, Katayama was able to take the podium with a third-place finish. He also put up a good fight in the final round of the British World GP, held that August. The fifteenth bike to pass the finish line, his machine was the first NR500 to finish a GP race. Moreover, Katayama made a strong showing in the West German Grand Prix, finishing in twelfth place.

The 1980 season, however, closed with just two events in which Honda's NR500s made it to the final round. Still, the machines were making steady progress, so it was still possible to build a point total and finish the season in tenth place or higher. However, the reality was that they were still trailing the 2-stroke machines by 10 or more horsepower. Therefore, even if the NR500s could advance in the standings, they did not have what it took to win a GP race.

Yanase recalled a sentence in the plan document he had received in December 1977. It read, "Become the world champion within three years." He knew that 1981 would be the final year in that attempt, so there was not much time left.

First Victory: The Suzuka 200-Kilometer Race

The oval piston engine underwent further improvements in order to reduce its weight, enhance output, and improve durability. The improved engine intended for the 1981 season had a smaller body, made possible by dropping the V-bank angle from 100 degrees to 90. Moreover, it had a maximum output of 130 ps at 19,000 rpm. Therefore, beginning with the 1981 season, Honda decided it wouldn't just compete in the World GP, but that it would also enter the All-Japan Championship Series. Honda made the decision to refine its NR500s more rapidly through participation in more races, hoping to build winning machines as quickly as possible.

In the second race of the All-Japan Championship, held at Suzuka Circuit in March 1981, the two NR500s ridden by Katayama and Kengo Kiyama both fell and retired. However, they had demonstrated considerable tenacity during the race, advancing to a point just behind the top group. In the next race held at Suzuka in April, the team saw one of its NR500s finish in fifth place. By this time, the NR500s were performing at levels equal to those of their 2-stroke counterparts.

In the Suzuka 200-Kilometer Race, the sixth All-Japan race held in June 1981, the NR500 ridden by Kengo Kiyama put on a strong performance, taking advantage of the higher fuel efficiency its 4-stroke engine possessed. Maintaining a large lead over its rivals, his NR500 went on to take the checkered flag.

Yoichi Oguma, the chief research engineer from HGA's Second Research Block who had joined the NR project in 1981 and became the first manager of the Honda Racing Team (HRC) the following year, had one vision: "Tactics and strategies also are important in winning the race. Honda is so preoccupied with the performance of its machines, but we can't win unless the machines, the riders and the team work as one."

This was a conviction that Oguma, a former All-Japan champion in the 125 cc junior class, had acquired through his own experience. Reflecting on that belief, the Suzuka 200-km Race - the sixth All-Japan race held in June 1981 - was run under his careful supervision, according to a calculated strategy.

Any 2-stroke engine running a distance of 200 km, or 34 laps of the Suzuka Circuit track, will require at least one pit stop in order to refuel. That means approximately 10 seconds in the pit area. Considering that the bike must decelerate to enter the pits and accelerate again on its return to the course, nearly 20 seconds must be given up. Oguma's strategy was to let his machines run the entire race without a fuel stop by making use of their higher fuel efficiency, which was of course the advantage of 4-stroke design. According to his calculations, the NR500s would save around 0.6 second per lap by eliminating the fuel stop.

The race was carried out according to plan. While the rival machines were making their fuel stops, Kiyama's NR500 gradually advanced, eventually passing the leader on lap 23. It was the first time an NR500 had led a race. What's more, Kiyama maintained his time, leading the race lap after lap. Coming out of the last corner first, his NR500 kept its lead and took the checkered flag. Three years after the start of development, the NR Block and its NR500 had achieved a victory.

The team was again victorious in July, when Freddie Spencer rode his NR500 to a first-place finish in a five-lap heat race held at Laguna Seca in California, which doubled as the qualifying round for an international race. It was with these victories that the NR500s were established as contenders in the ultimate challenge: to win a World GP race.

It was, however, still quite premature to assume that victory in a World GP event was theirs for the taking. That was too high a mountain to climb. After Katayama's thirteenth place finish at the first Austrian Grand Prix in April 1981, the riders continued to retire from subsequent races. The 1981 season ended without any point total for the Honda team.

Hence, the promise to become the world champion within three years was broken. The NR Block had found itself at the crossroads of victory and defeat, survival and abandonment

The NS500, Honda's First 2-Stroke GP Machine

The NR500s were indeed struggling to achieve any results on the World GP tour, and even the members of the NR Block had begun to lose their patience. After all, they had not been asked to demonstrate winning potential but to "win the race." The NR Block might have been just one of many groups within the Honda organization, but to the fans watching the race they represented none other than Honda itself. They just could not go on without a win, since a losing streak on the circuit would affect sales of Honda motorcycles and cars. Moreover, no action would be timely once the image of a powerless company had taken root among consumers. Potential was no longer enough. The development staff had no choice but to defend itself by winning.

Finally, a proposal to develop a machine carrying a 2-stroke engine was brought to the table for discussion. The proposed NS500 would have better performance than the NR500, at least theoretically, and the data - though it was basically a prediction - was not something with which anyone could argue. For its part the development team would no longer insist on the 4-stroke engine.

Thus, it was that the in the middle of the 1981 World GP season the NR Block began developing NS500 machines carrying Honda's first 2-stroke engine design. Assigned to the post of project leadership was Shin'ichi Miyakoshi (then the chief research engineer at HGA's NG Block), a veteran engineer who had designed engines for GP machines in the 1960s, during Honda's domination of the series. When the NR500 development started, Miyakoshi was designing engines for motocross bikes at HGA. After his motocross group had merged with the NR Block, he began working on motocross machines within the context of the NR Block.

Miyakoshi's original concept at the beginning of development was to make the NS500 a "compact, lightweight machine." Thus, once he had received the assignment to design a 2-stroke GP machine, Miyakoshi visited the Netherlands in June 1981, so that he could watch the Dutch TT Race held in Assen. There, he confirmed that there was basically very little difference in the lap times of 500 cc machines and 350 cc machines. The fastest bike in the 350 cc class could have started the 500 cc race from a position in the second row.

Accordingly, Miyakoshi envisioned a machine that, though it was a 500 cc unit, had the compact size of a 350 and a smaller frontal projection. Moreover, it would be equipped with an engine designed for optimal control rather than higher top speed. It would be a machine built to achieve total balance, and the idea had Oguma's full agreement.

Miyakoshi quickly aligned the vectors of staff members, each of whom was experienced at weight reduction through involvement with the NR500. From that point on, development would proceed rapidly. For reduced size, the engine would feature a unique 2-stroke, 3-cylinder V layout. With regard to the intake valve, the team chose a lead valve used for motocrossers rather than the usual rotary type used for road bikes. The lead valve was considered advantageous since it demonstrated no loss in power and push-started more easily. After all, a head start could give the machine a lead of at least three seconds, and those three seconds could well determine who crossed the finish line first.

The effort to reduce size went well beyond the confines of the engine. Having succeeded in getting a partner supplier to shorten the sparkplug, Miyakoshi then reduced the wheelbase by 25 mm. This made it possible to handle the 500-cc machine as easily as one would a 350. Furthermore, the NS500 incorporated the suspension technology Honda had accrued through the development of motocross bikes, greatly enhancing the combativeness and maneuverability of this new roadracer.

"A racing machine doesn't just consist of an engine and frame, " Miyakoshi recalled, "It's supported by the peripheral technologies of partner manufacturers. In developing our new machine, we learned a great deal from the advice given by the engineers at Mugen, an engineering company specializing in racing technologies. If the source of ideas had been limited to our staff members, omissions might have prevented us from achieving the right balance."

Although it was just behind Honda's 4-cylinder machines in terms of brute power, the NS500 had a maximum output of 120 ps at 11,000 r.p.m. and a maximum torque of 8 kg-m at 10,500 r.p.m. Additionally, the superb total balance of the machine fully compensated for any gap in power. Ultimately, the completed NS500 represented a cross between a roadracer and a motocross bike.

The NS500 team assembled to fight the 1982 season included Spencer, Katayama, and Marco Lukineri, who was the 1981 champion. Although the team regarded as their key force the NS500 machines powered by 2-stroke engines, they continued to race an NR500 under the ridership of Ron Haslam. Moreover, Honda refined its definition of responsibilities for the team manager, appointing Oguma to the post.

Victory Again: After Fifteen Years

Oguma, upon his appointment as team manager, promptly conducted a complete review of the team's organization. He was well aware that the successful management of his team, which included riders from overseas, mechanics and Honda staff from four or five different countries, would play a part in the results achieved on the circuit.

Oguma himself supervised the overall settings of machines. It was a process in which he had the support of Kiyoshi Abe, then chief research engineer at HGA's NR Block, who was a veteran of Honda's journey with the NR500s. Abe took charge of the carburetor settings, which in any racing machine required the greatest care. To better manage the team, the two promoted a sense of unity by communicating the originality of Honda's approach to all the staff members.

Knowing that the machine was not all that racing was about, Oguma encouraged his staff to see the races more often. So that they could thoroughly observe these events, he made sure the staff brought with them what he called the "Three Sacred Treasures" of racing: a camera, stopwatch and binoculars.

These things allowed them to measure not just the lap time but the running time at specific intervals, a practice that helped convey the relative characteristics of competing bikes. They even studied the compositions of rival teams and the roles of their members, along with how the other teams controlled their parts. They examined their rivals in many other respects, including how they set up their machines within a limited time so that the bikes would be in top condition when lined up on their starting grid. Oguma believed that in order for his staff to understand what Honda needed they would have to develop a critical perspective from which to analyze the actual race. In this way, Oguma aimed to create the strongest possible racing team.

When the 1982 season began, the fans found a completely different kind of team wearing the Honda emblem. In fact, the team scored a podium finish in the very first Grand Prix in Argentina, with Spencer getting third place. It was the first time since Honda's GP comeback in 1979 that a team rider had stood on the podium. In the seventh Grand Prix of Belgium held in July, Spencer again led the race, going into the final lap with a four-second lead over his nearest competitor. The staff watched nervously as his tricolor NS500 came out of the last corner. In answer to their hopes, Spencer rode to victory. He had given Honda its first win in the four years since its comeback.

It was also Honda's first GP victory in the 15 years since its retirement from the World GP. Then, in the tenth race held in Sweden that August, Katayama got the checkered flag. A critical factor in the rider's impressive performance was the collaborative effort of all staff members and support from Yoshio Haga, then chief research engineer in the Testing Block at Honda Carburetor Research Center. A specialist in carburetor operation who had tuned Honda's previous GP racing machines, Haga served as the team's advisor at the urging of Miyakoshi. Following the Grand Prix of Argentina, Haga became a real point man for the team. Along with Abe, he became the engine for the ideal team management that Oguma had so eagerly promoted.

The 1982 season ended with Spencer and Katayama finishing third and seventh overall, respectively. The NS500s won two races, and Honda finished third in its race for the manufacturer's title. Finally, it was a possibility that the NS500 could go all the way to the championship. Therefore, amid all the attention received by Honda's new 2-stroke bikes were getting, the NR500 retired from the World GP circuit. It was the end of the 1982 season, a year in which it had competed in two races.

Honda put major organizational changes into effect in September of that year. It integrated RSC (Honda Racing Service Center), which had been established in 1965 within Honda's Corporate Service Division in order to provide service for Honda owners participating in racing. Moreover, it had become independent in 1973, taking with in the NR Block and several functions of Motor Recreation Promotional Headquarters. The newly founded HRC (Honda Racing Co., Ltd.), which had a total of 203 employees and headquarters in the city of Niiza, Saitama Prefecture, thus became the world's first motorcycle racing company.

Honda's former European base of operations in the English town of Slough was relocated to Aalst, Belgium. The new office reflected the company's plan to facilitate team management by way of a European base for World GP activities. Hence, all preparations were in place, and Honda could fight for the championship title in the coming 1983 season.

Using Computer Analysis to Bring Honda Back, Stronger than Ever

Oguma spent as many as 210 days overseas during the 1982 season, and through the exertion of it all his weight dropped from 67 kg to 49 kg. Over the course of his time abroad, Oguma analyzed the race circuits, dividing them into those that were advantageous and those that would be possibly troublesome to the NS500s, which were less powerful than their rivals but superior in cornering performance.

He also studied the ways in which the machines won and lost. Of the victories, some might fall from the sky due to other rider's mistakes. A win by default was essentially different from a perfect victory. The same was true with the losses. He analyzed the details and summarized the results. The data clearly showed the weaknesses of NS500s and their degree of compatibility with each succeeding track. Therefore, to HRC, the year 1983 was to play a critical role, in which not only the result of each race but the result of the entire season would be scrutinized. Oguma wanted to help his machines earn higher positions through the effective use of strategies, as substantiated by data. He believed this would be the key to Honda's championship victory.

The championship race in the 1983 season ended up a dead heat. After beginning the season with three consecutive victories, Spencer continued to win on technical tracks. Although he was not able to beat Yamaha rider Kenny Roberts and his YZR on high-speed tracks, with each succeeding race Spencer accrued more championship points. When all but the final race had ended, Spencer had 132 points, while Roberts was close behind with 127 points. Spencer could win the championship title if he finished at least second in the last race.

The twelfth and final race was the San Marino Grand Prix. Yet, even amid the pressure of this important event, Spencer finished second to win the championship title. That race also secured the manufacturer's title for Honda. Therefore, even though the NR team was not able to keep its original promise of becoming world champion in three years, Honda had at last conquered the World GP series. It had taken five long, arduous years, but the smell of victory was sweet nonetheless.

Freddie Spencer gave an awe-inspiring performance at the South African Grand Prix in March 1983. That season, Spencer survived a heated championship race and grabbed his title in the final event. Honda even won the Manufacturer's Championship title, five years following its return to the World GP series.

The 1984 season saw Honda fighting it out with 2-stroke, 4-cylinder NSR500s as its key entries. Then, in 1985, the company competed in the 250 cc class with RS250RWs (a name that was changed to NSR250 the following year), which were commonly described as pint-size NSR500s. Crossing over with an RS250RW, Spencer became the first rider in the history of World Motorcycle GP racing to win two classes - the 250 and 500 - in a single season.

Honda went on to win numerous manufacturer's championship titles in the 125, 250, and 500 classes of the World Grand Prix and big-name riders like Wayne Gardener and Eddy Lawson dominated the tracks with their Hondas. In 1989, Michael Doohan was welcomed as the team's newest rider. Doohan subsequently won the 500 cc championship title for five consecutive years, from 1994 to 1998.

From the NR to Le Mans and Production Bikes

Honda had indeed conquered the World GP with its NS500s, but there were mixed feelings among the project staff. They could not forget the NR500s that had made way for the NS500s as Honda's primary machines in 1982, only to vanish from the World GP in 1983.

Oguma sent in a entry with a new machine to compete in the 24 Hours of Le Mans Endurance Race scheduled to be held in July 1987. Honda's machine was to be the NR750, an NR with increased displacement. The NR750 fared well in the qualifying round, but retired in the final. However, it won the Swan Series race held in Australia that December, blazing past its rivals in a decisive show of prowess. That race marked the final appearance by an NR series machine. Nine years after Honda first began their development under the goal of winning back the glory of the World GP series, the NRs had ended with a glorious victory.

Honda decided to fight for the World GP title with the NR500s, because it looked at the races as nurturing grounds for technology. Although the machines labored for years without a single point, they fostered the talents of numerous engineers and left behind precious assets. Among these were technologies that were later incorporated into production models; bikes that employed many of the weight-reduction techniques their NR ancestors had originated.

Honda introduced the new NR production bike in May 1992, powered by a 750 cc 4-cylinder V-engine with oval pistons. The machine employed an array of cutting-edge technologies, including an inverted front fork, aluminum twin tubular frame, and magnesium wheels. Thus, the NR500s completed their mission with the successful transfer of racing technologies to the production world.

The NR, introduced in May 1992, was powered by a 750 cc 4-cylinder V-engine with oval pistons. It boasted an impressive range of cutting-edge technologies, including an inverted front fork, aluminum twin tubular frame, and magnesium wheels.