Announcing the Civic / 1972

"Go to Suzuka and See the Line!"

A new development project got under way at the Wako R&D Center in the summer of 1970, a year after the Honda 1300 (H1300) was released.

Japan was then in the midst of explosive fiscal growth, achieving a rate of over 10 percent annually. Consumers, though, were beginning to demand more diversity in the products they could buy.

The Civic was designed to satisfy markets around the world. The car blended beautifully in city scenes, moving swiftly through busy traffic.

The nation’s infrastructure, also, was undergoing change. Since Japan was increasingly the host of such international mega-events as the Olympic Games and the World Exposition, it was necessary to demonstrate that this society was fully modern, with all the automotive accoutrements one would expect. Thus, Japan had struggled mightily to transform its transportation industry, and, consequently, car production leaped into second place, right behind the U.S.

Despite all that prosperity, Honda found itself struggling to survive allegations of defects in the N360. Sales of the H1300 were low, as well, prompting serious discussions as to what should be done.

"Go to Suzuka and see the line," Masami Suzuki, then the general manager of the R&D Center, told key project members prior to the official start of a new model development project. Yet, Shinya Iwakura, on assignment as a designer, did not quite understand.

"Why does he want us to go?" he wondered. "I only know that the H1300 currently produced at the Suzuka Factory isn’t selling well." When the project members actually saw the line at Suzuka, though, they turned white with shock.

"There were only a few H1300s scattered along the line," Iwakura recalled. "We were stunned by such a harsh reality." The others couldn’t hide their surprise, either. On their way back to Wako, the team members felt an overwhelming sense of pressure, which of course told them there was an impending crisis. Said Hiroshi Kizawa, who was engaged in Civic development as LPL, "We all believed that if the project failed Honda would have to give up its plan of becoming a full-fledged carmaker." Reflected in the gravity of that outlook was the series of failures Honda had experienced with its current cars, which threatened the company’s financial standing. Therefore, when the assignment came following their trip to Suzuka, the team members knew it would require a major effort.

"Give me a report," instructed Suzuki, "detailing the kind of car we should develop for the Japanese market and other markets around the world."

Two Teams, One Development

They knew the new theme would require an altogether different approach, so from the very start they would break from the conventional development process.

"Prior to that project," Kizawa said, "we’d been making a car that the Old Man (Soichiro Honda) wanted to build."

Honda’s previous models, in fact, had been developed based on the ideas of Mr. Honda, a man of consummate skill and genius. However, under the new project two teams would be formed, each consisting of around ten members. These teams were to work independently, and each was to come up with its own ideas. One team was led by Kizawa and included veteran engineers in their late 30s, while the other was comprised of younger engineers in their late 20s and early 30s. The purpose of this approach was to identify a better concept for their new car by encouraging competition between the two development teams, albeit with the same theme in mind. This configuration later evolved into the "free-competition approach through the concurrent implementations of heterogeneous projects," which was eventually promoted by Kiyoshi Kawashima, the senior managing director of Honda Motor, who later became president of Honda R&D as well.

Following a period of independent study and research, the two teams got together on the scheduled date to present their ideas. To their surprise, their answers were almost identical in concept, with only minor differences present in the details. Both groups defined their ideal car as "a world-class car that is light, quick and compact," identifying similar criteria for maximum speed and other performance parameters. Yet, beneath their concept of the ideal car was its exact opposite - the H1300 - whose ill fate they had witnessed at Suzuka, creating a near-crisis at Honda.

There is no denying that the H1300 had an excellent engine that outperformed its competitors in many respects. Even though it offered "superb quality in one specific area," it was decidedly out of balance in its overall presentation. To achieve outstanding engineering quality, other elements such as noise, comfort, and front/rear weight distribution had been compromised.

"We were all weary of the fact that we had made a car that was very good in certain areas but poor in others," Kizawa remembered. "We wanted to create a more ordinary car that could provide good quality in all aspects."

Iwakura, looking back upon the trip to Suzuka, said, "We may have been tricked by Mr. Suzuki." However, the trip had become the basis for an "ideal car" in each team member’s mind, and ultimately those ideas were reflected in the final concept. It was not a mere coincidence that the two teams arrived at nearly identical answers.

The car developed from this concept was later named the "Civic," meaning "a car created for citizens and cities."

Design in Pursuit of the Absolute Value

The Civic development project was, based on the report, reorganized to integrate requirements identified by the two teams. Hence, their assignment began in earnest with the goal of turning the concept into a successful commercial car. When the project was first started, Tadashi Kume was appointed LPL. Team leadership was subsequently passed on to Kizawa when the project entered the design phase.

One principle steadfastly maintained during development was to depart from the comparative approach of "increasing the interior dimensions by xx mm to match the dimensions of rival models." Instead, they focused on questions and answers, including "what kind of car Honda should develop" and "how that car can reflect the current market needs."

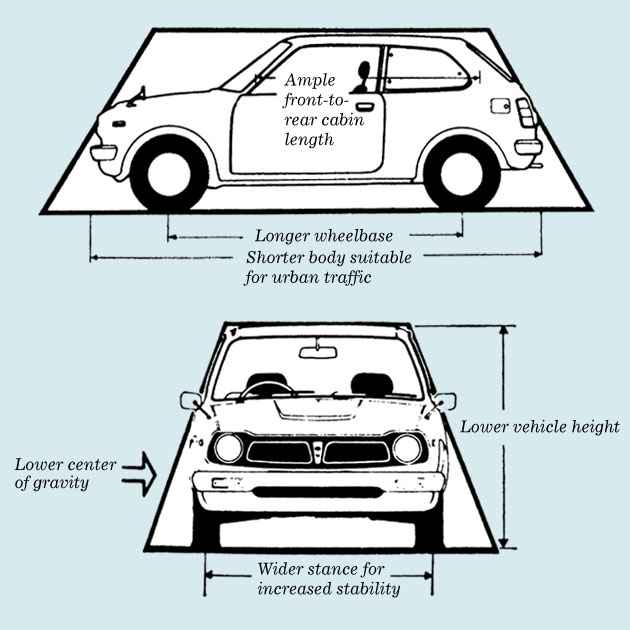

"We needed to define the ‘absolute value’ of our new car," Kizawa explained. It was through the pursuit of absolute value that the final concept for the Civic took shape. It was to be "utilitarian and mimimalistic, providing an optimal blend of size, performance and economy." Moreover, the notion of "man maximum with ample interior space" was incorporated to ensure a good balance of features and prevent the car from sacrificing creature comfort for the sake of efficiency. The specification derived from these concepts was a two-box car (with interior and trunk space integrated in one body section) featuring an FF (front-engine/front-wheel drive) format and transverse mounted engine. In those days, most compact Japanese cars employed the FR (front-engine/rear-wheel drive) format, along with a three-box specification that isolated the trunk space. The Honda team was thoroughly committed to achieving the absolute value, however, and therefore refused to conform.

It was not going to be an easy or quick process. As development moved forward additional targets were set and the engineers spent days in exhaustive trial and error searching for the right solutions.

The issue of weight, in particular, cost them considerable time and frustration. The target for the Civic, equipped with a 1200 cc engine, was to be 600 kg. But that was nearly impossible to achieve, given the weight levels of other Honda models: Even the Life mini car with a 360 cc engine weighed 540 kg, and the H1300 with a 1300 cc engine weighed up to 875 kg.

Yet, this lofty goal simply reflected a stream of logic that said, "the heavier it is, the more expensive it will be." After all, fuel economy could be benefited by way of weight reduction. In adapting an approach employed by engineers who had attempted to minimize the weight of Zero fighter planes during the war, the team gradually reduced the thickness of the sheet steel in increments of 0.1 mm. Accordingly, various structures were examined along the way. More than that, though, they used every single idea they could.

Kume, while the LPL, could often be found sitting on the warehouse floor amid an array of parts scattered around him. With drawings and a scale by his side, he would check each component, saying, "This one has to be lighter by ‘xx’ grams. This one is okay." Every team member understood, since each of them knew that every gram counted.

Although the initial target could not be reached, the team was eventually able to reduce the car’s weight to 680 kg.

Perseverance: Shrugging off Pressure from the Old Man

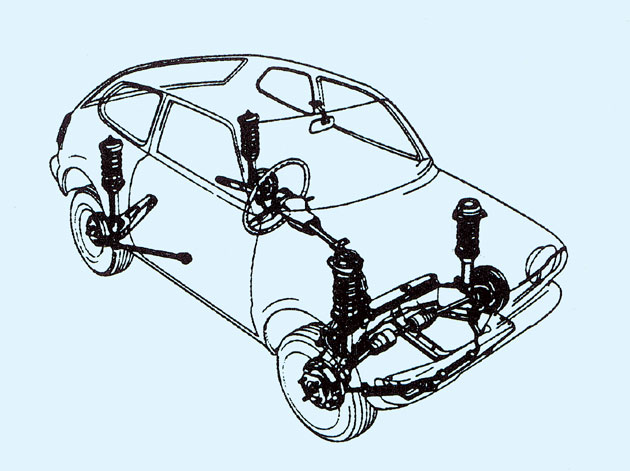

Weight reduction was one thing, but the achievement of higher rigidity without increasing costs was a different story. Mamoru Sakata, who was in charge of suspension design, spent days agonizing over the issue. At the time, most FF cars employed rigid rear-suspension systems (the right and left wheels are mounted on the two ends of a single axle). However, the development team had proposed that the Civic adopt a strut-type, four-wheel independent suspension system allowing separate control of the right and left wheels.

The four-wheel independent strut suspension system, still rare among FF cars, later became the mainstream among Honda’s compact and midsize models.

"Interior space would increase, thanks to the absence of an axle," said Sakata. "This method was also advantageous in terms of maneuverability, stability, front/rear balance and weight reduction. We knew it was the best choice for the Civic."

However, the rigid type was Mr. Honda’s favorite, due to its simple structure and higher productivity. Knowing his passion, the development team did not consult him, but quietly continued its work based on an independent strut suspension system. Eventually, Mr. Honda discovered their efforts, having chanced upon the strut-type system. A meeting was immediately scheduled to review the development specifications.

Sakata was feeling the pressure from Kume, who since stepping down as LPL had been working in support of the Civic’s development. "You must be prepared to shave your head if we can‘t keep the strut design," he said.

Sakata had indeed been forced to the precipice, and would have to confront Mr. Honda. He really did not mind the prospect, of shaving his head, since to him the adoption of a strut system was much more important. Throughout the process Sakata would refuse to yield under any pressure to give up the strut system. Then came the moment when he was called into the boardroom, where Kawashima and Mr. Honda were waiting.

Sakata found himself feeling relatively uninhibited despite the powerful presence of the company founder. He spoke openly, with remarkable confidence and no sign of frustration. Completely absorbed in the topic, he described the advantages of a strut-type independent suspension and how important it was to adopt the design. Struts were, he claimed, essential to making the Civic a world-class car.

Mr. Honda was displeased, despite Sakata’s best efforts. "I don’t see any merit in the independent suspension," he said flatly. When Sakata turned to Kawashima and asked for a comment, he was pleasantly surprised to receive a show of support. "At least Mr. Sakata is passionate about this idea," he said. "Maybe we should let him pursue it."

Under the coaxing influence of Kawashima, Mr. Honda realized it wouldn’t be easy to refuse, and he simply said, "Okay, then do it."

Kawashima had indeed helped, but it was Sakata’s uncompromising conviction that had shrugged off the pressure from Mr. Honda to win approval for the use of an independent strut suspension.

Eliminating Trunk Space: A Daring Decision

Prior to the start of the development project, the Japanese government had been busily drawing up its People’s Car Program*1. When the team obtained information that the program’s details were at last final, and that passenger space was to be limited to 5 square meters, the team was confident that the Civic’s "utilitarian and minimalistic" concept was in conformance with the program. Based on that blueprint they began defining the dimensions of their first-generation Civic.

Honda’s planned retail dealership sales channel was a key factor affecting the dimensional constraints. At the time, most of the company’s associated dealers were small motorcycle shops. Thus, in order for those shops to carry the car, the interior passenger space had to be kept under 5 square meters.

The initial development specification was 1,450 mm in overall width and 3,300 to 3,400 mm in length, based on the prescribed conditions. However, the width was subsequently increased to 1,505 mm, since the original dimension had been deemed insufficient for an FF car equipped with a transverse 1,200-cc engine. Accordingly, the team was forced to cut the overall length by 100 mm or more in order to keep the occupancy space to a maximum of 5 square meters. Of course, a comfortable cabin had to be provided within that space. It was a tough call to make.

The project members were naturally expecting their car to have a stylish silhouette. Contrary to those expectations, however, the car grew wider and shorter with each passing day. Before long, the layout depicted a chubby, trapezoidal car that had no trunk.

"The Civic was modeled on the contours of the Life," said Iwakura. "The original layout had smoother lines at the rear, and there was a distinctive trunk section. But every day the car got shorter and shorter. Finally, we made the decision to eliminate the trunk space so as to prevent the shape from becoming ambiguous."

This daring move gave birth to the unique styling of the first-generation Civic; a "three-door hatchback design featuring a trapezoidal profile." This was, in fact, a style already somewhat common in the U.S. and Europe, though it was rare in Japan.

Iwakura stressed to his colleagues that the Civic’s unique styling was "part of its character," and would become part of the car’s absolute value. And since the team wanted to create a car that was small yet offered "pride of ownership," that profile was the perfect choice.

"Taking motorcycles as an example," said Iwakura, "a rider on a Monkey can be proud of his bike even when he’s running next to a big 750-cc machine, because the Monkey has a unique character. So, we spent many hours thinking about how we could give our car that kind of character. For example, we could imagine promotional phrases like ‘simple yet charming.’ But I was looking for adjectives other than ‘charming’ that could fit perfectly after the word ‘yet’ in the slogan for our car." Development gradually moved forward and, at last, the various technologies and designs comprising the Civic’s skeleton could be combined as a total form.

Normally at this stage, an S·E·D (Sales, Engineering, Development) joint evaluation meeting is held. According to the results, the design and/or specifications may be subject to change. With the Civic, a slightly different approach was used. Rather than deliberate the matter further through a subsequent series of meetings and discussions, the project team was given relative autonomy. Suzuki himself took the lead in encouraging the project members.

"Let’s move in the direction you believe is right," he said. "We’ll ignore the voices in the background until we have an actual car."

The Civic was, in fact, kept in the hands of Honda’s development engineers until an actual prototype could be completed. During that time the team worked diligently in pursuit of the absolute value they had defined. While the achievement of quality was certainly admirable from the perspective of engineering and design, they knew the car would have to succeed with the customer out in the marketplace. It was a message that they could not forget.

Note:

*1 The People’s Car Program: Under the program (announced when Honda was developing its first-generation Civic), the Japanese government proposed that compact cars designed and priced for ordinary Japanese people should fit in a space of 5 square meters or less. In reality, the program imposed no legal obligations on the maker or customer.

The Car without a "Tail"

The initial feeling at the R&D Center with regard to the Civic’s styling was somewhat negative. In fact, many people there doubted whether a car with such a shape could find a home in the market. Later, when the Civic was unveiled to the sales staff, Yoshihide Munekuni, then general manager of the Kagoshima sales office, raised his hand with a question. Referring to the phrase "three-door," he asked seriously, "So, on which side is the third door located?"

The members of the development team, who were there to explain the car, immediately burst into laughter.

"All of us in sales were sitting there perplexed about what they meant by ‘three-door,’" Munekuni said. "Our reactions were very much in contrast to what they were telling us." That simple question, though, perfectly described the public’s minimal understanding of the "three-door hatchback" concept at the time.

The "trapezoidal" style, however, was the only way to achieve a real-world expression of the hatchback concept. So, in order to gain an understanding of the Civic’s significance as a work in design, Iwakura decided to start with company associates. To make the concept easier to understand, he used various expressions such as "The car is stable because of its trapezoidal geometry," and "It isn’t slender and graceful like the delicate fingers of a woman, but rigid and powerful like the clenched fist of a man."

The novel styling of the first-generation Civic, which was a trapezoidal shape from every angle, was the result of considerable daring on the part of its designers.

As a result of these efforts, the trapezoidal profile that was once so alien to the public gradually became familiar. The design soon won overwhelming industry support, particularly among automotive experts and journalists who were familiar with foreign models. "Their view changed significantly," said Kizawa. "And though it was a bit of an exaggeration, some critics were saying that if you didn’t understand the Civic, you didn’t understand cars at all."

The project members, who had at one time prayed in earnest for the car’s commercial success, regained their confidence as the positive reviews began pouring in. By the date of its official release, everyone was convinced the Civic would sell.

The line-off ceremony for the first-generation Civic in July 1972 raised the expectations of every Honda associate.

The Civic hit the market after only two years of development, which was at the time an industry record. Honda released its two-door model in July 1972 and the three-door GL in September.

"One night," Iwakura remembered, "Mr. Kume took me out for a drink to celebrate the launch. We began talking with a waitress there, and Mr. Kume decided he’d introduce me as ‘the guy who designed the Honda Civic.’ Then she said, ‘Oh, I know what that is. It’s a cheap car, isn’t it? Because all expensive cars have tails (trunk). The Crown has the longest tail, and the second is the Corona. The Publica has a very short one. But the Civic has no tail, right?’ So, to be honest, I was completely shocked by her comment." Their confidence was high, even though in the minds of the project members there was the lingering question, "What if?" But before long they were greeting each other in the morning by saying how many Civics they had seen on the streets the day before.

Evolving into the World’s Standard Car

The consuming public, as was the case with Honda associates, was initially confused about the Civic’s styling. And the Civic didn’t exactly scorch the showroom floor immediately after its official launch. That trend improved, however, with the release of the three-door GL. It proved very popular with the youth market and became a big hit, pushing the model’s production volume to more than 12,000 units one month. Although the first year’s sales figure was a modest 21,000 units - given a mere five months remaining when the first two-door type was launched - the Civic went on to sell 80,000 units in 1973. Sales continued, also, exceeding 60,000 units each in 1974 and ’75.

The Civic’s 1972 debut earned it an outstanding level of recognition, with the first of three consecutive Motor Fan Magazine Japan "Car of the Year" awards.

The Civic was also honored with the Japan Car of the Year Award in 1972, 1973, and 1974, becoming the first ever to win three years in a row. In Canada, the Civic remained the number-one import car in volume for 28 consecutive months from 1976 through 1978. These achievements amply demonstrated the car’s design innovation and broad public acceptance, both in Japan and overseas.

The popularity of the Civic in overseas markets was given an even bigger boost with Honda’s response to the Clean Air Act of 1970. The company had announced that the Civic’s engine would be in full compliance with the emissions control regulations, at a time when other manufacturers were struggling to meet them.

An attributive factor in that response was a new development system that had been introduced by Kawashima. The primary element in his system was the separation of R&D themes into their respective categories of "R" research" and "D" development. For instance, the development of a new model would be classified under D-development, where the process was essentially performed by combining current technologies. On the other hand, the creation of a significant new technology would be implemented as R-research. This allowed Honda to develop its CVCC engine quickly, and thus meet with regulatory compliance ahead of any other company. Honda had also established a system of evaluation meetings enabling project members and top management to share their opinions on engineering issues. These meetings dramatically enhanced the quality and accuracy of development tasks, and in the process shortened the development cycle. It is a system that continues today in support of Hondaês development activities.

Thanks to these new systems, Honda’s low-emission CVCC engine was adopted to the Civic and released in December 1973. The Civic CVCC model received high recognition in the U.S. as a car that truly satisfied consumer needs.

The U.S. car market was at the time undergoing dramatic change due to increased environmental concern. Along with a shift from leaded to unleaded gasoline, carmakers began designing models with fuel systems that did not accommodate leaded gasoline. Unfortunately, the oil crisis of 1973 cut supply of unleaded gasoline to the U.S., and people everywhere were forced into long lines at the gas stations in hopes of purchasing a tank of unleaded fuel.

New models having catalytic converters could only use unleaded gasoline, since the lead present in conventional fuel would react with the materials in the converter, causing dangerous heat buildup. However, the Civic’s CVCC engine had no such device because it was equipped with a mechanism that effectively cleaned the exhaust gas in the combustion process. In other words, the car could run on either type of gasoline.

"The catchphrase for our Civic promotional campaign was ‘Any Kind of Gas,’" said Munekuni, who at that time was working for American Honda in its automobile sales operations. "The advertising campaign for the CVCC engine conveyed a positive company image to the consumer, who felt that Honda had high standards in technology." The Civic’s excellent fuel economyãa product of comprehensive weight-reduction efforts such as a lightweight body - effectively reduced driver dependency on gas stations and their lines of gas-starved customers. In fact, the EPA’s fuel-economy tests rated the Civic the most fuel-efficient car for four consecutive years, beginning in 1974. Thus, the Civic became the basis for Honda’s subsequent compact cars. Moreover, it became the world’s standard in the perception of what a car could be, thanks to generous media support and the forethought of Honda engineers, who had endeavored to satisfy increasingly diverse public tastes with a car suitable for the new era in energy conservation.

A History of Absolute Value, Generation After Generation

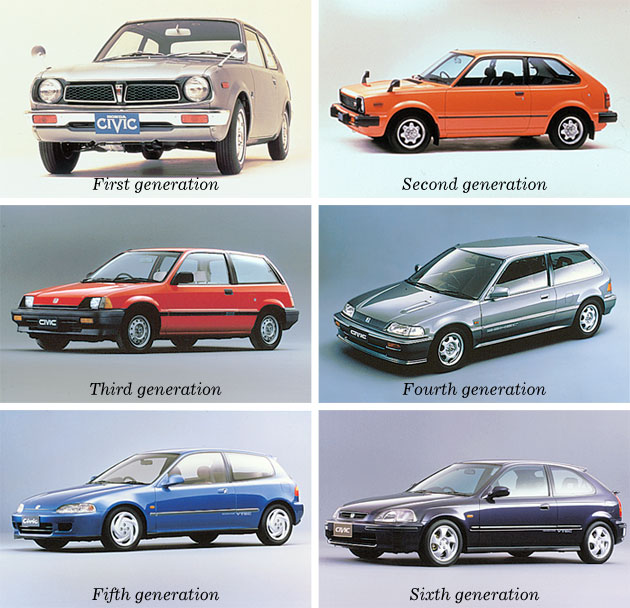

Looking at the six generations of Civics (1999 marking the 27th anniversary of the Civic), we can easily discern the presence of a unique and original concept. With each succeeding model year, the concept has been preserved and refined. In fact, each generation of the Civic has expressed its underlying philosophy in a different way, thanks to an impressive series of designs and technologies.

The Civic’s six generations have enchanted us with their different faces.

For example, the third-generation "Wonder" Civic was popular for its revolutionary design, notably an extended roof. The fourth-generation "Grand" Civic adopted a high-output VTEC engine that incorporated a natural intake mechanism derived from F-1 racing. The fifth-generation "Sports" Civic achieved dramatic improvements in fuel economy through use of the VTEC-E engine, a refinement of the VTEC technology that debuted in the Grand Civic. The sixth-generation "Miracle" Civic adopted a CVT transmission system designed to absorb shock during gear shifts, thus providing smoother operation across the rev range. Over the years, Civic has earned a total of six Japan Car of the Year Awards (three consecutive years with the first generation and one each with the third, fifth and sixth generations). In 1995, the model’s worldwide cumulative production volume surpassed 10 million units. The car also was honored by the Ministry of International Trade and Industry in recognition of its innovative technology. Using the expression of some, the Civic has served as a "trend-setting car."

Twenty-seven years ago, Honda’s development engineers created a car by defying the conventional approach. Instead they gave their ideal a tangible form and shared that creation as a gift to the world. With the development of each successive model, those engineers have relived the joy and satisfaction that exist as a motivating force in Honda’s ongoing search for new technologies.

At one time, the Civic was a product without a name. It was during this period that Iwakura received a phone call from Kiyohiko Okumoto, then manager of the Sales Promotion Division. Even to this day, Iwakura remembers it well.

"We have come up with a name for the new car," Okumoto said. "But I wanted to check with you, since you know the car more than anyone else. The name is ‘Civic.’"

Iwakura shivered with excitement when he heard the name, for it was then that he knew their ideal had been conveyed. He was happy that the sales branch understood what the development engineers had tried to achieve. Thus, in retrospect, it is not surprising that Kizawa and Iwakura gave identical answers when asked to describe the Civic’s identity:

"We must always imagine the satisfied faces of our customers, and be confident in the kind of car we want to create for them. Unless we work to convey our ‘ideal’, we won’t make a car that’s good enough to satisfy them. But with the Civic, we could carry out our ideal completely."