Formula One Entry: The Initial Phase / 1964

"What is F-1?"

In May 1962, Hideo Sugiura, quality manager at Saitama Factory, received an unofficial order from Yoshihito Kudo, director of the research center, "We are planning to compete in F-1. I want you to oversee the project." The resulting exchange was a rather interesting one:

"What is F-1? I have seen some photographs about it before, but I don’t know what it is. Please tell me what F-1 is," asked Sugiura.

Soichiro Honda and the F-1 prototype car which was covered with a steel space frame like that of the Cooper Climax on which it was modeled

"I don’t know, either," replied Kudo. "It doesn’t matter. Everyone’s a beginner, at first." This conversation is just an example of how foreign a concept F-1, or Formula One, was to Honda’s employees at that time. What little information available to them came from the 2.5-liter British F-1 machine, the Cooper Climax, which the research center had obtained six month earlier.

Honda’s entry in F-1 was announced in January 1964. Ever since the company had won an overall victory at the Isle of Man TT Race, one of motorcycling’s most prominent races, there had been great anticipation concerning Honda’s possible move into car racing. Particularly, the employees of the research center were confident that there was no race that could not be won with their technology.

Despite the previous year’s launch of the T360 mini truck and the S500, a small sports car, Honda was still the youngest car manufacturer in Japan. It was none other than Soichiro Honda who decided to compete in F-1, before any other manufacturer in the country.

Mr. Honda’s passion had been evident since March of 1954, when the company announced its entry into TT motorcycle racing. "Since childhood," he once said, "my dream was to become a champion in world automobile racing with a machine I had made myself." Thus, Honda once again took the fateful first step toward the realization of a dream, this time in the world of cars.

Only a small number of engineers were assembled to handle the F-1 project at first, most of whom had been involved in motorcycle events only. Therefore, to conduct the necessary research and development experienced engineers were hired, and young employees fresh out of college were recruited to provide much needed manpower. The new R&D team was led by the company founder.

"The target for horsepower was decided by Mr. Honda himself," recalls Akio Okudaira, who was in charge of engine performance. "Whether that horsepower could be achieved was not the question. He just told us we must produce this much power in order to win. For example, the code name for the engine, RA270, was assigned by Mr. Honda, who probably wanted to remind us that the engine had to produce 270 horsepower."

The Challenge: Building a Complete Machine

The drafting of detailed layouts for the prototype RA270 engine was started in August 1962, and by June of the following year the team was ready to test its performance. Their prototype F-1 car, which, like the Cooper Climax on which it was modeled, was covered with a steel space frame, was tested in Arakawa on February 6, 1964.

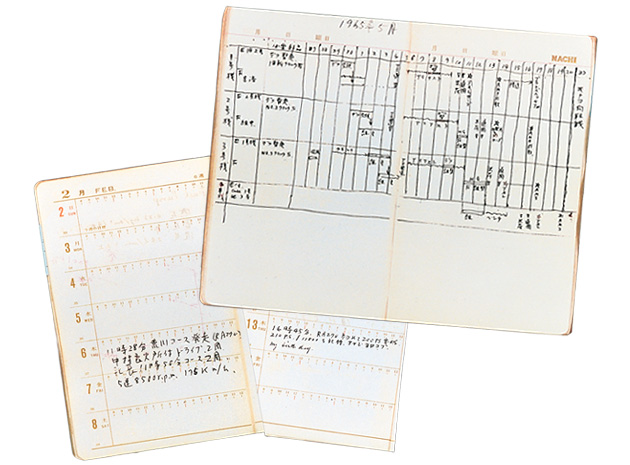

Mr. Honda and Yoshio Nakamura, assistant director of the research center (later becoming the first F-1 team manager), drove the metallic-gold car two laps around the course. The RA270 recorded 8,500 rpm in fifth gear, with a maximum speed of 175 km per hour. The following week, on February 13, the RA270 tested at 210 horsepower with 11,800 rpm, exceeding the 200-horsepower mark for the first time. Fujiya Maruno, an engine design engineer who witnessed the test, made this entry in his notebook: "The Old Man is happy."

The notebook of Maruno, in charge of engine design. The entry for February 13, 1964, reads, "The Old Man is happy."

"The Old Man (Soichiro) had been racking his brains. He used to come to the design room and tell us we should do this and do that before going home. Then, he would come back the following morning and ask us what had happened. Of course, by that time he had a different, better idea with him. He wasn’t getting enough sleep, either. It was like that for a long time, so it was no wonder he was so happy that day," says Maruno.

The test car’s chassis was built at the research center, but the center also had to devote its resources toward the development of passenger vehicles.

Nakamura discussed the matter with Mr. Honda, and it was decided that they would build only the engine and have European teams use it in their own chassis designs. Nakamura flew to Europe in summer 1963, visiting several F-1 teams and promoting Honda's engine.

Finally, Lotus was selected to be their partner. However, in January 1964, when they were ready to ship the engine, the partnership collapsed due to a situation that had arisen on the Lotus side. Honda had to build the chassis by itself after all. Of course, they were plagued with problems, from design and materials to parts and components, since the company had relatively little experience in auto manufacturing, not to mention racing machines. Each day, their designs were changed following rebuttals by the shouting Mr. Honda.

All these efforts, however, were rewarded when the first race-ready F-1 machine, the RA271, was finally completed. The body was painted ivory white, and the front nose donned a vivid red circle symbolizing the Japanese flag.

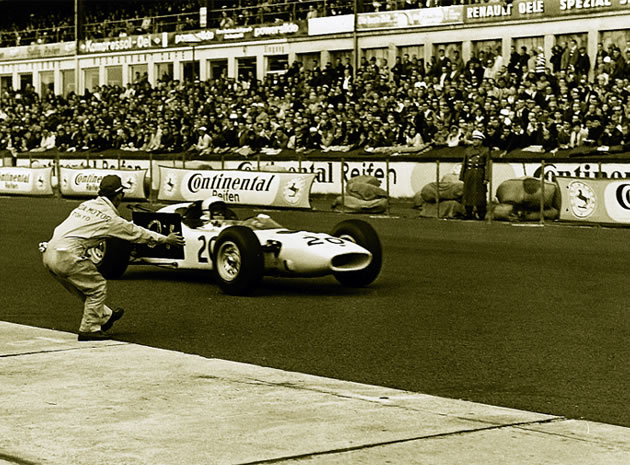

The first attempt was the German Grand Prix held in August 1964. The driver was Ronnie Bucknam. Regrettably, the RA271 crashed out of this highly anticipated debut race, only three laps before it was to cross the finish line. However, the car was running in ninth position when it retired, and it gave great confidence to the team after a disappointing qualifying round in which the RA271 could not complete a single lap.

The August 1964 German Grand Prix, the initial F-1 race in Honda’s first phase

That year, the RA271 competed in three races, but ended up retiring in all of them. The team’s staff was not at all pessimistic about its performance or prospects, though. Instead, the thinking was on how to make use of the knowledge acquired from those three races, and apply it to the next season.

Celebrating the First Victory. The Mexican Grand Prix

The following year - 1965 - Honda decided to compete in Formula Two in addition to F-1. The F-2 engine design team was led by Tadashi Kume and Nobuhiko Kawamoto (both future company presidents), with the final engine scheduled to be supplied to Jack Brabham’s team. Ron Tauranac took charge of the chassis design. Little did they know that they were soon to experience a painful season in both events.

The losses kept coming in F-2. The team spent night after sleepless night trying to figure out what had gone wrong. If they could not clearly explain the reason, Mr. Honda would shower them with his merciless "You, stupid!" Facing overwhelming pressure, and driven into a corner, the members of the development team were soon at the point where they were unable even to eat.

Their F-1 work focused on improving the RA271 that they had raced the previous season. Accordingly, its chassis material was changed from duralumin to corrosive-resistant aluminum alloy, and the overall weight was reduced with the engine and other components adopting lightweight materials and designs. They also signed a second driver, Ritchie Ginther, and sought his advice on how to improve the machine.

Five races later, they were still struggling. Ginther had completed just two races, and his best result was just sixth place. Back at the research center, the homebound team members had been encamped for two months, trying to improve the engine’s cooling performance while lowering its center of gravity for enhanced handling. With all these efforts, however, both machines retired with engine problems in the subsequent Italian Grand Prix. At the U.S. Grand Prix, a large leaf got sucked onto the radiator of one machine, causing its engine to overheat. It seemed the team was simply unable to score a victory on behalf of Mr. Honda, who had come there to cheer them on.

The last race of the Grand Prix season, held in Mexico, took place on a circuit 2,000 meters above sea level. It was there that the drivers were faced with conditions that did not exist at any other Grand Prix circuit, meaning the thin atmosphere of a 2,000 meter elevation. However, in this environment Honda’s fuel-injection mechanism worked very effectively, and on October 24, 1965, Ginther’s RA272 immediately leaped to the front of the pack, where it stayed until the finish. Honda had at last won its first victory, a feat that had come just two years after the team’s F-1 debut.

The victory gave ample proof that Honda’s engine and chassis technologies were world-class.

Richie Ginther (center) and Nakamura share the joy of their first victory at the Mexican Grand Prix in October, 1965

"Although the carriers are different, the technologies remain the same. When I began to think that way, I became much more confident," recalls Shinichi Koike, the team’s mechanic. "I usually worry about loose bolts and the like whenever our machines are positioned on the starting grid. But in that race I was sure we’d done everything right. When I saw our machine turn the last corner in first place, I couldn’t keep from trembling."

Soichiro gave a press conference after receiving the news of his team’s victory at the Mexican Grand Prix. "Ever since we first decided to build cars we have worked hard and been willing to take the most difficult path," he said. "Now we must study the reasons why we lose, and do the same when we win, so that we can use that knowledge to improve the quality of our cars and make them safer for our customers. That’s our duty. Once we had established our goal, we decided to choose the most difficult path to get there. This is why we entered the Grand Prix series. We will therefore not be content with this victory alone. We will study why we won and aggressively apply those winning technologies to new cars."

The 3-liter Engine Was Too Heavy

The displacement standard for F-1 engines was scheduled to change to 3.0 liters in 1966. At Honda, a conceptual model for the new engine was finalized in the fall of 1965, after which the drafting of a detailed engine layout began. However the design engineers were wearing themselves out with many projects, and at the urgent request of Takeo Fujisawa a prioritized sequence for engine design was decided. Top priority was given to the N360, a mini automobile scheduled for launch in October 1966. The F-2 and F-1 engines were fourth and sixth on the list, respectively.

The first race of the 1966 F-2 season was called off due to heavy rain. However Honda dominated the second race, taking first and second place. What followed was an amazing string of eleven consecutive victories. Thus, taking this F-2 engine as an example, the team began the construction of a new F-1 engine with which to fight the 1966 season.

However, the team had virtually no experience in the design of 3.0-liter engines, so it was necessary to start from scratch. It was not until summer, halfway through the season, that a race-ready RA273 was completed. The engine’s output exceeded 400 horsepower, but the chassis weighed more than 700 kg. This was because too much emphasis was given to the machine’s rigidity in order to compensate for high engine output, which was almost twice that of its predecessor. This caused the machine to lag behind its rivals in overall performance.

The new engine debuted in the Italian Grand Prix on September 4, with everyone putting in their best effort to prepare the machine. Finally, it was time to move up to the starting line.

Mechanics adjusting the 3.0-liter engine before the Italian Grand Prix in September, 1966 (Photo courtesy of Teijiro Hagita)

"During the one week at Monza," Okudaira remembers, "the only things that stayed at our hotel were our suitcases. We camped at the garage every night. We slept standing up, not realizing we were sleeping until we were prodded by someone."

To their disappointment, one of Honda’s machines failed to finish the race. The tires burst on the seventeenth lap due to its excessive weight and enormous power, causing it to jump the guardrail and crash into a tree. The car was completely destroyed. By the time of the subsequent U.S. Grand Prix, the machines were carrying thin-walled stainless-steel exhaust systems as a weight-reducing measure. However, Bucknam had to retire after his tailpipe cracked. Ginther could not finish, either.

The problem of weight remained a critical one, even after the race.

The Long Trip to Monza

Honda decided to temporarily withdraw from motorcycle and F-2 racing until 1966, and the engineers, who had been designing the machines, began designing commercial mini automobiles. By 1967, the research center was busier than ever. That year, Honda signed John Surtees - the only man in the world who became world champion in both the Motorcycle and F-1 Grand Prix series - as a driver for the F-1 team.

Although the RA273 finished third at the South African Grand Prix, the first race of the 1967 season, it had to be scrapped after only a few races. However, its engine was modified to produce greater output, and was mounted in the new RA300.

To make the machine more competitive, in midseason Nakamura and Surtees decided to build a completely new, lightweight chassis through Lola for the Italian Grand Prix. Therefore, Honda sent Shoichi Sano, who was in charge of chassis design, to Lora. The completed RA300 achieved an output rating of 420 horsepower, while keeping the chassis weight to 610 kg.

The Italian Grand Prix, held on September 10, was to be an historic race. In the last stretch on the way toward the finish, leading drivers Surtees and Jack Brabham were running only a few meters, or 0.2 seconds, away from each other. Eventually, Surtees’ RA300 finished first, bringing Honda a second victory to complement its first win at Mexico two years before.

Surtees’ machine (left) getting the checkered flag in the Italian Grand Prix in September 1967. The lightweight chassis, developed jointly with Lola, contributed to the team’s second victory.

The following day, when the team was returning to London from Milan Airport, the members were congratulated by people at Alitalia Airlines, who had made special arrangements for the team to board the plane first. Suddenly the real excitement of victory sank in among the team members, who realized just what a feat they had achieved.

"This honor was a product of our joint development effort with Lola," Sano says. "The engine supplier took all the credit for the victory, while regrettably the chassis constructor stayed in the shadows. However, after the victory people gave us cynical comments, saying we should be called ‘Hondala,’ not Honda. But in a sense the event prompted Honda to form a new strategy for its second phase of F-1 racing, in which it decided to supply engines only."

The Question: Victory or Technology

Everyone was confident going into the 1968 season. After five years of hard, painstaking struggle, the team had accumulated sufficient technical know-how, finally coming to understand exactly what its strengths and weaknesses were. At last, they understood what was needed to win the Grand Prix.

Therefore, the order by Soichiro Honda to develop an air-cooled F-1 engine came as great surprise. The N360 carrying an air-cooled engine, released in March 1967, had become a best-selling car. Assured by the N360’s success, Mr. Honda greenlighted the development of the H1300 - a new model to be equipped with an air-cooled engine - in order to gain a foothold in the passenger-car market. Mr. Honda was convinced that world-class cars must be powered by air-cooled engines. However, he wanted to prove the superiority of Honda’s technology in the F-1 arena before applying it to the company's commercial models.

Honda eventually decided to build both water-cooled and air-cooled engines for the 1968 F-1 season. The opinion of Nakamura, who wanted to win the race, and that of Mr. Honda, who believed racing to be a proving ground, led to a "water-cooled engine vs. air-cooled engine" debate that divided the research center.

The F-1 RA301, carrying a water-cooled engine, competed in all races. However, it only finished three: the French Grand Prix, where the machine scored its best, second-place result; and the subsequent British and U.S. Grand Prix races, where it finished fifth and third, respectively.

"In terms of overall competitiveness as measured by the combined power of men and machine," said Surtees, "Honda had a good chance of winning several races, including the Belgian Grand Prix and Italian Grand Prix. The fact that we lost these races means we simply didn’t have good luck." His comment was a strong indication that by then the team had sufficient technology and excellent teamwork.

The air-cooled F-1 RA302, on the other hand, could not have had a worse debut. At the French Grand Prix held in July, in which the machine competed after a rather abrupt decision just before the race, the RA302 crashed, leading to the death of its driver, Jo Schlesser.

"When one competes in a race, an ‘A or B’ approach will never work," says Kawamoto, who at the time was designing water-cooled engines at the same time as his involvement in air-cooled engines. "We must concentrate on one strategy in order to win. Mr. Nakamura was right from the viewpoint of a racing team. However, the logic of the Old Man, who wanted to build an air-cooled F-1 engine as a stepping stone to developing and successfully marketing mass-production cars powered by air-cooled engines, was also correct from the viewpoint of a company."

"One strong reason behind the push for air-cooled engines was Mr. Honda’s strong belief in the engine," recalls Kume, who was in charge of the development and design of air-cooled engines. "However, having been involved personally in the project, I must admit I was excited with the opportunity to do something no one had ever done before. Of course, none of us had expected such a tragic ending.