Establishing Belgium Honda / 1963

EEC: Leaping the Hurdle into Europe

By June 1961, sales of motorcycles by American Honda Motor (American Honda) were registering some momentum. At about this time, Honda established a wholly owned sales company, European Honda GmbH (European Honda, presently Honda Motor Europe (North) GmbH) in Hamburg, Germany (then West Germany), in order to expand its exports overseas. Just as it had done in the U.S., Honda took up the challenge of opening a European motorcycle market.

Ironically, that month Honda swept the top five spots in the 250 cc and 125 cc classes at the Isle of Man TT racing event in the U.K. It was only the third year that Honda had participated in the event. Honda was indeed making a name for itself throughout Europe and the U.K.

In fact, Honda was at the time the world's leading maker in terms of motorcycle production and exports, and the Honda bikes were making a mark on the racing circuits with outstanding performances in the British Isles. Therefore, if Honda could succeed in the establishment of a European market - already a major one, with annual demand exceeding two million units - it seemed the day would soon come for the company to be recognized as the world's number one motorcycle manufacturer, with the reputation and sales figures to match.

European nations, however, had lately been implementing severely restrictive importation policies in order to protect their domestic industries. Therefore, it was clear that limits on imports and high tariffs would make it hard for Honda to win in this critical market.

It all began when six European countries-West Germany, France, Italy and the three Benelux*1countries-made the move toward enhanced economic unity. In January 1958, the European Economic Community (EEC) was established (the predecessor of today's European Union, the EU). The leading nations of Western Europe sought greater force in competing with two giant political and industrial powerhouses, the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

The EEC countries were planning to establish a common EEC market by the end of 1969, in which they would mutually abolish tariffs among the six countries and combine their respective markets. Their way of dealing with countries outside the EEC region was to establish an import-restriction policy involving high tariffs and import quotas.

The EEC's policy was to promote the growth of industries in its home countries by providing regional corporations with the privilege of unrestricted, tax-free distribution in a huge market. Countries outside the EEC region, however, would have to pay dramatically higher tariffs in exchange for import rights.

This meant that Honda motorcycles, after two months and considerable transportation expenditures, would be subject to an additional high tariff at customs in order to complete their voyage from Japan to the Port of Hamburg, the city in which European Honda was located. As a result, Honda would not break even unless the motorcycles were sold at a significantly higher prices than their European counterparts. To make matters worse, the EEC continued expanding its protectionist policy so that the gap in tariffs between Honda and the regional manufacturers of motorcycles continued to widen, causing Honda to become less competitive in the market.

Many countries, including Japan, did not really take the EEC's policy too seriously, believing it could not be easily organized or enforced since government policies and economic structures varied throughout the region. But they were eventually forced to change that view, and began scrambling for the means of coping with the situation.

Note:

*1 The three Benelux countries:Belgium,the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. The name is derived from the Benelux Customs League, a postwar charter established in January 1948.

Fujisawa Assigns a Local Investigation

News of the EEC's policy was frequently reported in the media of Japan and other nations throughout the month of December 1961. The measures Honda would conceive in order to handle the situation were to play a key role in its overseas strategy. During that period, following a meeting in the Executive Boardroom, the topic of conversation between Takeo Fujisawa (then senior managing director) and Hideo Iwamura (then assistant general manager of administration) turned to a possible strategy regarding the EEC. Fujisawa described in considerable detail the present state of the EEC, along with future trends and issues facing Honda in the EEC region.

The exportation of motorcycles to the EEC was rapidly approaching the specified limit, yet even at that point Honda was barely making a profit. Moreover, the high tariffs were threatening to consume even more of the company's earnings. It was feared that motorcycle exports would no longer be feasible as a business when the EEC combined itself into one big market. Therefore, in order that Honda might grow its business on even terms with competitors within the EEC, it was argued that the best measure would be to have Honda produce and sell motorcycles within the region.

Successful production and sales within the EEC could dramatically cut the costs of distribution. Furthermore, the simple increase of locally procured parts to 60 percent of product content would qualify the product as EEC-made, enabling it to be distributed tax-free within the EEC market. After all, Honda motorcycles had already demonstrated their great potential in local race activities, and opportunities were on the increase for the development of a European market.

"So then," said Fujisawa, "you start looking into it right away." With that, Iwamura was instructed to conduct a market survey in the EEC region, under the assumption that Honda would establish a corporation for the local production and sale of motorcycles. Iwamura, surprised by such a sudden turn of events, simply could not hide his bewilderment.

"This is a very important issue concerning Honda's future," he said. "So, let's tackle it by organizing a solid system first."

"I'll leave everything to you," Fujisawa replied. "Feel free to do what you think is best." Following the exchange, Iwamura hurriedly began work on a research project for the EEC region.

By January 1962, Iwamura, along with Kenjiro Okayasu (then manager of Saitama Factory's Direct Materials Section, Materials Division) and Tetsuya Iwase (then chief of the Training Subsection, Personnel Division), organized themselves as the "Special Planning Team for the Corporate Project to Expand into the EEC Region," and began full-scale preparations to conduct the necessary research. There was relevant data to collect with regard to the issue. Yet, for the meantime their research would center on the choice of a candidate site for the construction of a local corporation that could produce and sell motorcycles using materials and labor procured in the area. Moreover, they would need to determine the size of the operation and the types of motorcycles that should be produced. That was no easy task, considering that the EEC was comprised of countries that differed greatly in terms of their policies, economics, market characteristics, languages and customs. It was highly likely that such differences would affect the way any corporation engaged in business there. Moreover, in choosing a site for factory construction it was obvious that the host nation had to be politically stable with a good economic foundation that allowed for the local acquisition of parts. Other factors in the equation were the need for a skilled labor force and a convenient geographic location for corporate activities. Considering the need to satisfy so many conditions, their research took on a wick scope.

A Decision by the EEC Research Team

The research team thus began to focus on West Germany, the EEC's most stable economic power, as the best candidate for factory operations. The team decided to stop by European Honda in order to get a briefing on the market situation, after which the research would continue in West Germany. Therefore, at the end of January 1962, the trio of researchers headed for Hamburg, with Iwamura leading the way.

The three members of the research team spent more than two weeks traveling through West Germany's major industrial cities, collecting information for analysis. Along with the progress in their work came a certain realization regarding the European market; an assessment that no preliminary research, book, or other resource could have provided.

It was the moped*1 that had entered the picture. The wide use of these vehicles throughout the region was much more than the team could have anticipated. Of the estimated annual demand of 2 million motorcycles in Europe, about 80 percent was for mopeds. Many European streets even had special bicycle/moped routes bordering the sidewalk. Thus, the moped had long since established itself as a popular means of transportation in the region.

France was the EEC's top producer of mopeds, with annual production exceeding 1 million units. Other major producers of mopeds were Italy, West Germany, and England. Much like the Japanese motorcycle industry surrounding Honda in its earliest days, a number of small midsize manufacturers were producing mopeds in different factory locations.

Moreover, it was soon apparent that West Germany had numerous drawbacks. For example, it was home to several major manufacturers of motorcycles and mopeds, including BMW. Its labor market was nearly fully employed, and the minimum wage had reached a fairly high level. West German prices were also higher than any of the remaining five EEC countries. It would therefore cost considerably more to obtain a decent-size lot for the construction of a factory, buildings, facilities, and the employment of many people.

The research team thus expanded its purview to include all the EEC countries, with the exception of Luxembourg. Soon, as the team compared and examined conditions in each country, Italy and France were scratched from the list for much the same reason as West Germany. In the end, only two countries remained: the Netherlands and Belgium.

Among the EEC countries, the Netherlands and Belgium were somewhat behind in terms of modern industrialization. However, since the launch of the EEC they had been working to promote industrialization by actively soliciting funds, including foreign investments. Therefore, both nations greeted Honda's research team with open arms, enthusiastically inviting Honda to establish a factory in their country. Government officials personally escorted the research team on tours, introducing a variety of possible sites.

After seeing first-hand the conditions in the two countries, the researchers began to favor Belgium as the more appropriate location.

Belgian cities already had many factories. Though small, these factories were known as highly reliable suppliers of parts to the carmakers of West Germany. Moreover, the minimum wage was low compared to West Germany's, and the prospects were good concerning a sufficient pool of skilled labor. Added to that was a major push by the small city of Aalst, which began to woo the research team during their tour.

Aalst was a small town with a population of about 50,000, located within a 40-kilometer radius of both Brussels (the capital) and Antwerp, a free-trade port city. While Aalst and the two cities were connected via expressways, there also was a canal connecting Aalst to Antwerp, upon which goods could be transported. Moreover, the city fulfilled all the conditions for corporate activities, including materials procurement.

The research team ultimately chose Brussels as its candidate site for the construction of Honda's European head office, which would double as a sales base, while Aalst was selected as the candidate site for factory construction. The two-month research tour had at last concluded, and the team was ready for its return to Japan.

Note:

*1 Moped. Mopeds refer to European bikes that are equipped with pedals. In Japan, they are now called 'mopetto.' While mopeds were by law restricted to engine displacements of 50 cc or less and a maximum speed of 40 kilometers per hour (varying somewhat amoung countries), they also were given tax privileges in taxes, insurance, and special traffic rules. Moreover, the minimum operating age without a license was sixteen years. The moped - actually a kind of motorized bicycle, belongs to an entirely different category than motorcycles such as the Super Cub and scooter.

The First Japanese Company to Establish a Factory in the EEC

A team of twelve was put together in May 1962 for the establishment of a new company, Belgium Honda Motor. All became members of the Special Planning Team. Iwamura, who had led the EEC research team, was assigned as manager of Belgium Honda in order to oversee regional production and sales. Okayasu was assigned to the factory manager's post, where he could provide general instructions regarding factory construction and production activities. Iwase was assigned the job of factory administration manager, in which he would facilitate production activities.

To obtain permission from the Japanese government to establish Belgium Honda, members of the Special Planning Team compiled an outline of Belgian corporate activities into a document entitled "Prospectus for the Establishment of a European Factory." Armed with files of materials, the members paid numerous visits day after day to the Ministry of International Trade and Industry, the Ministry of Finance and the Bank of Japan, repeatedly describing the situation to officials.

As with the establishment of American Honda three years earlier, in 1959, the Japanese Government would impose strict restrictions on the removal of foreign currency from the country, citing a lack of foreign currency.

It was apparent that approval would not be an easy thing. Although many Japanese corporations had already established overseas sales bases - American Honda being a noteworthy example - Belgium Honda was to be the very first establishment of a production base overseas. Moreover, such a production base required several times the amount of foreign currency that a sales base did.

The government officials were resolute in their answer. "We cannot give you approval for such a large amount of foreign currency," they said, "unless you have the potential to earn profits commensurate with the investment."

Negotiations pressed on, however, during which Honda was able to gain the government officials" understanding on its intent to launch a production operation in the EEC region. However, the focus of discussion had shifted to the actual amount of foreign currency that could be taken out of Japan. The officials wanted to keep that amount to a minimum, while Honda wanted to secure enough funds to establish a factory in Belgium without any unnecessary problems.

Therefore, even though it was not the full amount Honda had initially requested, approval was given for a total of 75 million Belgian francs. (This was an amount equal to about US$1.5 million at the exchange rate of that time, 20 percent of which was to be investment in kind).

The government officials were not particularly hopeful concerning the outcome of this, the first overseas production operation undertaken by a Japanese company. Even so, they set aside their skepticism and decided they would step back and see what happened.

Belgium Honda acquired a 90,000-square-meter lot for factory construction. This was roughly equal to 10,000 square meters, the size of Saitama Factory's Wako Plant. The factory itself would cover 5,000 square meters, encompassing facilities for welding, painting, assembly, and final inspection.

Moreover, three types of motorcycles would be produced: mopeds, constituting approximately 80 percent of the EEC's motorcycle market; and two Super Cub models, the C100 and C110. The monthly production capacity was to be 10,000 motorcycles, based on a single-shift system. Since mopeds were not then part of the Honda product line, they would be designed at the R&D Center in Japan. "Knockdown" production was planned with all parts to be obtained locally except for the engine and a few others to be imported from Japan.

Completed products were to be sold to the three Benelux nations through Belgium Honda, while European Honda would sell them to the remaining EEC nations.

"You might think that [the monthly production capacity of 10,000 units] was unreasonably small for a market that had yearly demand of more than 2 million motorcycles," Okayasu said. "But it was the first time [that Honda or any Japanese corporation had engaged in overseas production]. So we thought along the lines of rearing a small child and raising it to adulthood." We believed that we should strive to sell as many as we could so that after establishing a track record, we could enlarge the factory for enhanced production capacity."

A Mere Eight Months to Completion

The official groundbreaking for Belgium Honda's factory at Aalst took place in October 1962.

Hoping to be ready for the coming spring's motorcycle sales season, Iwamura needed to have some completed products, even if it meant only a few of them. He gave instructions to proceed with construction on the factory operation, which was set to begin in February 1963.

The construction schedule allowed just over four months, from start to finish. For the Belgians, however, such a plan seemed rather unreasonable. The work had been contracted to a Belgian firm whose company officers came to Ryoji Matsui, the man in charge of factory completion, landscaping, and power, with a different suggestion. "In Belgium," they said, "it rains or snows more than half the year. We simply cannot make an irresponsible promise regarding the exact date that work will be finished. So, we'd like you to think in terms of the number of actual work days written here." With that, they began to explain the process, referring to their schedule.

That document detailed the various processes of construction and the schedule for work, including the number of actual work days needed to complete each step. However, the scheduled completion date for each process had been left blank.

"In Japan," Matsui said, "when construction falls behind schedule, the contract assignor and the contractor know what to do without having to discuss much. They'll try hard to catch up, even if it means increasing the number of workers or speeding up construction by working overtime and on weekends and holidays. But things didn't work that way in Belgium. In fact, the law prohibited them from working on weekends or holidays."

The actual construction, however, moved along at an incredible pace. In fact, at one point it seemed their work would be completed in time for the start of operations in the spring. Winter was still upon them, though, and soon the entire region found itself in the throes of a major cold snap. The ground froze solid, and was then buried under deep drifts of snow. Construction had to be delayed, forcing an increase in the number of days needed. The Japanese employees stationed at Belgium Honda began to worry, saying, "At this rate, we'll never make it in time for the start of operations this spring."

To make matters worse, that December the Belgian government issued an order prohibiting outdoor construction out of concern for those working in the extreme cold. As a result, Honda's entire construction process had to be put on hold. Therefore, Belgium Honda's Japanese associates decided to use that time to establish routes for the procurement of parts. After all, these routes would be their lifelines for regional production. Still, they knew there would be many obstacles. Although they searched all of Belgium for companies that could supply parts made to Honda's specifications, they could not seem to find one. The search had to be extended to the Netherlands and West Germany.

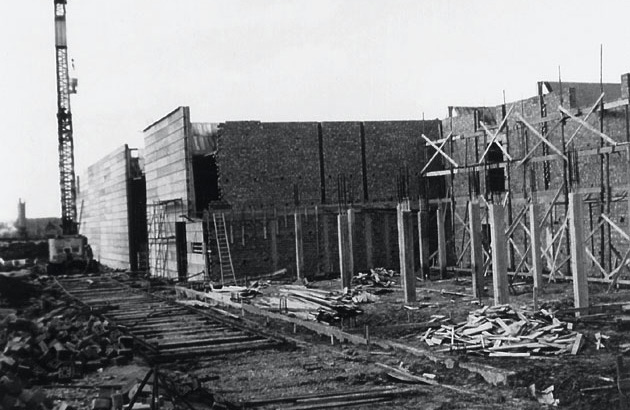

Building the factory in Belgium. The construction was rapid from the start, but nevertheless was suspended for four months after a cold wave struck the region.

Building the factory.

Laws were already on the books in Europe concerning consumer protection and the assurance of product reliability. Manufacturers were obliged to continue product supplies for at least ten years once they were on the market. Moreover, they were obliged to maintain sufficient inventories for that period. Such laws affected local parts manufacturers greatly in the way they managed their businesses.

For example, the leading production method was to complete a lot of parts on order. Therefore, for a company to supply Honda, it would have to employ new facilities to meet the demands of mass production, if it did not already have them. It was hardly a positive situation, since the price quotations Honda began receiving were several times higher than those it could get in Japan.

Further creating difficulties for Honda was the fact that Belgium had no industrial standards resembling Japan's JIS (Japanese Industrial Standard). That the situation varied among different countries in Europe made obtaining parts even more difficult.

The winter delay had dragged on for four months, but at last construction work could be resumed. It was March 1963. "It was one crash project after another," Iwamura recalled. The local people, too, were astonished at the speed with which things were being done. On May 27, 1963 despite the fact that a portion of the building was yet unfinished, the factory shifted into operation, producing its very first Super Cub (C100).

Front view of the factory at Belgium Honda. Today it produces automobile parts.

"We were able to complete factory construction in the eight short months, counting the period in which work was suspended, only because of the dedicated efforts of Belgium Honda's staff, along with our contractor," explained Okayasu. "The local people had at first found it difficult to comprehend our method of first deciding on the factory's opening date and then finding ways to meet that goal. But once we reached our goal, they said, "This is certainly a different way of getting work done!" After that, they really began to trust us."

Getting Started - Without the Know-how

Becoming the first Japanese manufacturer to initiate production operations in an EEC country, Belgium Honda now found itself in the limelight, both in Japan and throughout the world.

On May 27, 1963, the factory went into operation. The first Super Cub rolled off the production line.

Even so, many difficulties lay ahead for the Japanese associates stationed at Belgium Honda, as well as the 180 or so local people who worked with them at the factory. At that time, Honda Motor had just begun to employ knockdown parts for its export products. Accordingly, there was as yet no thorough system for knockdown operations, so no one could call themselves an expert. Therefore, at Belgium Honda, they had to build a knockdown production system from scratch, developing as they went their particular form of expertise. Daily production activities would serve as their guide.

"At first," Iwamura recalled, "some parts we received were found to be defective. And often we weren't able to operate the line because the parts hadn't come in on time. Once, when the parts didn't arrive because of a strike at Customs, we even went to talk with them directly. We had to plead with them to end the strike."

Many of Belgium Honda's local associates had no experience in mass-assembly operations, further complicating matters. Therefore, the number of motorcycles produced per day was initially a very small number. Under instructions of the Japanese staff, the associates would repeat the process of assembly and disassembly over and over, thus enhancing their skills. And eventually production activity got under way on a respectable level.

"The problem of maintaining quality was the first thing we had to deal with, once we had started factory operations," Okayasu said. "But we also worked hard to create a friendly, trusting environment in which the Belgians and Japanese could work together."

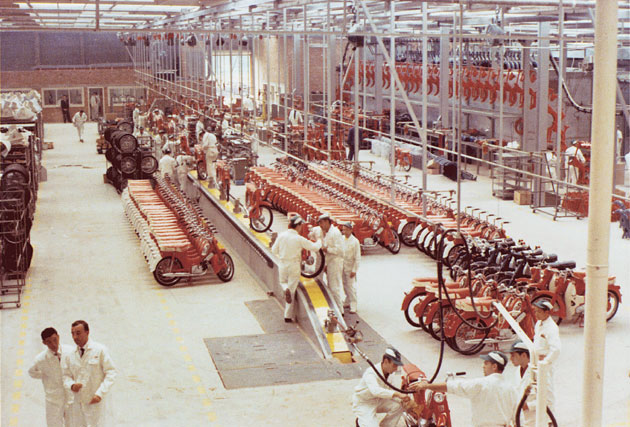

Assembling products at Belgium Honda

The greatest hurdle for Belgium Honda's Japanese staff, in fact, was the difference in customs and languages. Given that Belgium was, and still is, a country with two national languages - French and Flemish, the latter being the Dutch-derived dialect of northern Belgium - the regional culture was an equal mix of those traditions. Thus, it was not at all like the situation in Japan. Moreover, the capital city of Brussels was the dividing point between the two languages. Flemish was spoken mainly in the area north of Brussels, including Aalst, while French was spoken in the south. This considerably affected communication among the associates. In addition, most Japanese staff spoke only a little English, and only one of them was fluent in both English and French. Business instructions from the Japanese staff, both at the production site and sales office, were conveyed to the associates through English-speaking Belgian managers. Therefore, it was not long before the Japanese staff began to experience the frustration of not being able to communicate their opinions freely. They were constantly aware that extra time and effort would be needed in order for them to communicate through interpreters.

The Japanese staff also had difficulty understanding the local way of thinking which was based on a contract-oriented social structure and age-old hierarchal class system. Accordingly, opinions and perceptions would often be at odds during the process of cooperative work. Such issues were always resolved, though, thanks to the mutual efforts and discussions of all involved.

"Even if there were differences in languages and ways of thinking, we couldn't make great products without conveying our thoughts to one another," Iwamura said, looking back at the period. "I'd always told the [Japanese] staff in the field to discuss what they wanted to do with the local people, no matter how long it might take."

Honda Sweeps the Isle of Man TT Race

Belgium Honda celebrated its first anniversary with a factory opening ceremony on September 5, 1963, when Honda Motor was about to celebrate its 15th anniversary. The following day, with the help of local officials, a grand gala was held in an 18th century castle rented for the event. The party was attended by many, including officials from the Belgian government and officials from Aalst. Soichiro Honda, the president and founder of Honda, also flew in from Japan.

The factory's September 1963 opening ceremony was arranged so that it would coincide with the first anniversary of Belgium Honda's founding. Soichiro Honda flew in from Japan to share the joy with his local associates.

(Photos courtesy of Mr. Hideo Iwamura and Mr. Ryoji Matsui.)

"Honda swept the Isle of Man TT Race, and now the company's boss is coming to Belgium," the locals said of Mr. Honda's visit. In the sky was a light airplane slowly circling with a streaming banner carrying the message "Welcome, Mr. Honda!"

Europe was at the time a heavily class-conscious society in which there was great distinction made between management and factory workers. It was simply a matter of course that there was a clear difference in status between white-collar staff and blue-color workers. Thus, it was unthinkable for the president of any company, no matter how big or small, to speak directly with his associates or even shake their hands. Therefore, when Soichiro Honda addressed the local associates in the opening ceremony he said, "Let's have fun working together as one." He even approached a circle of associates saying, "Let's have our picture taken together."

The locals were not only happy to be greeted that way, but were truly astonished at the company president's forward manner. It helped set the tone for the gathering, and everything went smoothly from that point on.

The local community was generally very friendly toward the Japanese associates at Belgium Honda. They delighted in having the company of Japanese people, who were then very rare in the region. Moreover, the families of the Japanese were always being invited to parties as part of an effort by the local people to engender their friendship.

There were those, however, who frowned upon Belgium Honda's participation in the regional market.

The use of mopeds in Belgium and the Netherlands was comparatively high with respect to the other EEC nations. Therefore, Honda was perceived as a threat in certain ways, having demonstrated world-class performance in the Motorcycle World Grand Prix and the Isle of Man TT Race.

"There was initially a period in which we couldn't get as many applicants as we wanted," said Iwamura, "despite the ads we'd placed in the newspapers. But the local papers were running such reports as, The General Motors of Japan arrives, rampaging through the market," and Honda invades the market." So, we decided to run an ad pushing our concept into the spotlight, saying something like, We're launching our activities for the development of the Belgian motorcycle industry. We'd like to see our products used not only in Belgium, but in other countries as well." And that was the turning point. It helped clear up any misunderstandings among the local people, and the number of job applicants grew dramatically."

Factory Encounters the Risk of Closure

Despite having conquered a number of obstacles before and after the factory's opening - including a ferocious cold wave and differences in corporate culture, language and tradition - more problems lay ahead for Belgium Honda in its effort to get on a path to full-scale production.

The most troublesome of these was the fact that the company's new moped (Type C310), which they'd worked so hard to create and market, simply was not meeting their sales expectations.

Moreover, problems began to occur with the customers' products soon after the startup of the new sales network. Increasingly, products were being returned to the factory with user complaints attached.

The C310 moped had not been designed and developed as a specific response to local market demands. Actually, it was a remodeled version of an existing product, put together after it was decided that Belgium Honda was to be established. Therefore, only a limited amount of time could be devoted to meeting the moped regulations stipulated by European nations. There was a greater need to concentrate on the factory's opening.

The C310 was a remodeled version of the Super Cub, a product that had achieved monumental success in Japan and the U.S. In the moped configuration, though, the power of the Super Cub's four-stroke engine was cut back so as not to exceed the maximum speed of 40 kilometers per hour. As with other mopeds in Europe, pedals were also added to the product. The Honda version, however, was larger and heavier than the two-stroke mopeds then so common in Europe. To the local public, the Honda moped looked more like a motorcycle than a moped.

Honda's moped was marketed based on the assumption that Europeans, who were generally taller and more heavily built, would embrace it. However, the C310 never managed to capture the hearts of local riders.

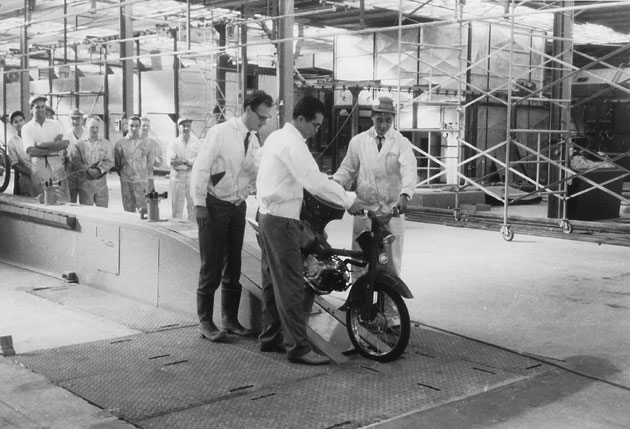

Test-driving the new type of moped (C310) assembled at Belgium Honda. This moped had a hard time winning local acceptance.

In fact, many problems arose, including those in which users employed a mixture of gasoline and oil in the four-stroke engines, just as they did with their European mopeds. So, despite the enormous effort to convince dealers and customers that the four-cycle engine was superior in all respects, and having provided thorough instructions on how to service the vehicles, the sales increase that Honda wanted simply did not appear.

Company funds were dwindling, too, and this prevented Honda from obtaining fully qualified parts. The situation at Belgium Honda began to deteriorate, with many other factors coming into play. Soon it seemed that the factory would have to close.

The Future: A Lesson in Overseas Expansion

Mr. Fujisawa paid a visit to Belgium Honda out of concern for the situation. "In the end," he said, "the basic rule of factory operation is to produce only as much product as can be sold." Therefore, after that, Belgium Honda began working together with the local associates in an effort to rebuild. So valiant was the effort, in fact, that not a single associate was laid off. The associates of Honda factories in Japan, as well as the R&D Center, even contributed, helping to support Belgian production and product enhancements. For their own part, most of the local associates chose to stay with the company and share in the hardships faced by the Japanese staff.

Unfortunately, though, the challenges were to last many more years, despite numerous attempts to improve things.

In 1964, Koichiro Yoshizawa was assigned to manage the Sales Division at Belgium Honda, in the hope that the company could be revitalized. Several times, Fujisawa told him "Once you withdraw, you'll never be able to come back again. To do so would entail a tremendous amount of money and effort, and it would most certainly hurt our reputation. So, we'll also help you out from Japan. Please see the situation through, no matter how tough it gets."

The EEC's original policy had thus been a very real threat to Honda's business activities in Europe, and in response, the company's top leadership had decided to establish factory operations in the region. Accordingly, the factory was launched through the concerted efforts of numerous associates, who in overcoming differences in language and culture managed to establish a system of their own.

The Japanese way of thinking and doing things, however, was not always compatible with the ways of its European hosts. As a result, the company could not fully comprehend the demands of the European market, and this brought significant hardships to Honda's people, including many local associates.

The hardships, on the other hand, became assets that Honda could apply to its eventual expansion overseas. Many of those who experienced trying times in Belgium later became involved in Honda's global growth, helping run production bases around the world. The bitter lessons of their Belgian experience were to be quite useful in the success of future efforts.

"The Belgian experience was one of hardship in every aspect of work, including production, sales, development, and management," Yoshizawa recalled. "But through such experiences, I believe the lessons learned about corporate activities overseas were effectively conveyed to the Honda associates by word of mouth. It probably wasn't even necessary to put them down in writing."

Belgium Honda did rebuild, though, and is now an important producer of automotive parts as well as a marketer of motorcycles, cars, and power products. Prior to that, in 1978, Honda Europe was established in Gent, Belgium, as a center for the distribution of products and parts located along a canal front, convenient to expressways and railroads. Today, Honda Europe single-handedly prepares the distribution of automobiles shipped from Japan for the European market, and provides supplies of locally obtained parts. By removing some of the burden that would otherwise be placed on Honda corporationas throughout Europe, it plays a major role in improving services and the distribution of goods throughout the continent.

Honda Europe enjoyed a very smooth launch, thanks in large part to years of work in Belgium, during which Honda earned the praise, understanding and cooperation of the local community.

Accordingly, the Honda Belgium Fund was established in 1981 for the purpose of supporting cultural and technical research exchanges between the two countries. The offices for this venture were set up Belgium Honda, which continues as a leader in Belgian-Japanese cross-cultural activities.

Belgium Honda, having gone through years of hardship, had thus succeeded in extending its range of activity to many areas. It is a success story that would not have been possible if it were not for the hard work, dedication, and integrity of so many, including the Japanese staff, local associates, and people of Belgium.

Note: Honda's employees are also referred as to "associates."