Establishing American Honda Motor Co. / 1959

Achieving a Breakthrough in America

"We have now established ourselves on solid ground domestically," said Senior Managing Director Takeo Fujisawa. "Eventually, we'll have to aim to be number one worldwide. So, with that in mind, why don't you go check out the overseas market?"

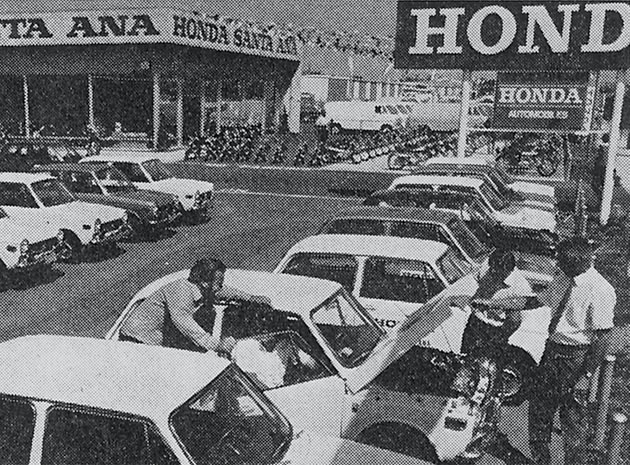

American Honda shortly after its establishment

The order had thus been given, and Kihachiro Kawashima, then manager of the Sales Section at headquarters, began his preparations to study the Southeast Asian market. It was a logical step for the company to take, since it had within a mere seven years established itself as a top manufacturer in the Japanese motorcycle industry. And now the expansion of exports to overseas markets was a very real possibility, reflecting a shift in Honda's policy from domestic fulfillment to a more international profile, featuring such products as the Dream (in 250 cc and 350 cc versions) and Benly (125 cc).

Honda soon began exporting sample motorcycles, about which Fujisawa was emphatic. "Instead of relying on a trading company," he said, "we should first take a look at the overseas market for ourselves. Then we'll find the best way to do business there."

Honda conducted market surveys in Europe and Southeast Asia from the end of 1956 to early the next year, with the former being covered by Soichiro Honda and Fujisawa and the latter taken by Kihachiro Kawashima.

In Southeast Asia motorcycles and mopeds imported from Europe were making their first appearances in the cities and towns, signaling the emergence of a popular new means of transportation that would soon rival the bicycle. In fact, as the region's economy grew, motorcycles were expected to outstrip bicycles.

Kawashima conducted a survey that lasted for more than three weeks, after which he returned to Japan and reported to Fujisawa that the Southeast Asian market was indeed promising. In return, Fujisawa told Kawashima, "Now, go off to America and check it out," ordering him to conduct a similar survey in the U.S. The country that Kawashima saw was truly the Land of the Automobile. After all, cars were an absolute necessity amid the vast expanses of rural territory, which had for years lacked a viable commuter network of railroads. And motorcycles were seen merely as adjuncts to cars, like toys one could use for leisure or, if one was daring enough, racing.

"I had always thought that motorcycles provided a means of transportation with which one earned a livelihood," Kawashima recalled. "Sure, they doubled as toys from time to time, but mainly they were used for everyday necessities. So, in my view America didn't come across as a country that had really accepted the motorcycle."

Upon his return from the U.S., Kawashima made a proposal to Fujisawa: "I believe it would be easier to begin with the Southeast Asian market than America."

Fujisawa considered the suggestion for a moment, then turned and gave a firm reply. "On second thought," he said, "let's do America. After all, America is the stronghold of capitalism, and the center of the world's economy. To succeed in the U.S. is to succeed worldwide. On the other hand, if a product doesn't become a hit in America, it'll never be a hit internationally.

"To take up the challenge of the American market may be the most difficult thing to do," Fujisawa concluded, "but it's a critical step in expanding the export of our products."

Building the Honda Sales Network

It was by no means unanimous that Honda should go it alone, however. Some directors insisted that the company should enlist the help of a trading company in exporting products to the U.S.

Fujisawa, though, had already decided not to rely on a trading company, saying he preferred that Honda develop a sales network of its own. Eventually American Honda Motor Co., Inc. (American Honda), was established as a wholly owned sales division of the parent company. Moreover, Fujisawa instructed Kawashima, then just 39 years of age, to relocate to the U.S. as the general manager of the new American company.

Fujisawa had the benefit of considerable experience building Honda's domestic motorcycle sales network. He was also aware of the pitfalls that awaited businesses when they depended on third parties to do their legwork. He was afraid Honda would not be able to do business as it wished when the other company's interest took priority. Moreover, he believed that selling durable goods such as motorcycles implied a responsibility for service after the sale.

It was a bewildering question for Kawashima. "I wonder if I'm really up to this big job," he thought. "What a huge project they've given me!" He had no choice, then. Knowing he couldn't simply give up before attempting anything, he went to work on the establishment of American Honda.

Kawashima chose Los Angeles in November 1958 as the most likely location for Honda's American offices, following a tour of several candidate cities. Los Angeles had a warm hospitable year-round climate, with minimal rainfall. Since climate was a determining factor in sales, the fact that there was so little rain meant the company could be in business all year long. It was the perfect environment for American Honda.

Los Angeles was also home to many Japanese-Americans, about whom Kawashima felt a certain kinship. For Kawashima, who would soon be taking up an enormous task in a land he knew so little about, the presence of this community was a boon to his morale. These were fellow countrymen, he thought, who would be there to back him up.

His investigative tour thus concluded, Kawashima quickly drew up a plan for the establishment of Honda's new American sales division. This plan, however, would require the approval of the Ministry of Trade and Industry and the Ministry of Finance, since foreign currency was to be taken out of the country in order to establish a corporation overseas. Government regulations were in place to control how much currency could be taken out of Japan.

Honda's application to take out foreign currency in the amount of $1 million in capital funds (then approximately 360 million yen) was mercilessly denied by the Ministry of Finance. The ministry maintained that a motorcycle maker such as Honda couldn't possibly succeed in the United States, when even a major car manufacturer that had established a sales company there was experiencing great difficulties.

Kawashima continued his visits to the Ministry of Finance, hoping to settle the issue. Finally, in April 1959 Honda was given the approval to take out foreign currency in the amount of $250,000 in capital funds. This, however, was under the condition that cash equal to just half that amount would be taken out of the country. The rest was to be taken out in the form of products or investment in kind.

A Wind from the West, Blowing Across the American Landscape

Kawashima relocated to his L.A. post in June 1959. His first task was to look for an office property that could serve as American Honda's official business location. After shopping around, Kawashima decided to buy a former photo studio on West Pico Boulevard using some of his admittedly limited funds.

"I felt that we had to put down roots and establish our own building," recalled Kawashima. "So I thought, ‘Let's not rent for the time being. Why not just buy the building?' It might have seemed reckless, but I didn't feel that I was acting out of desperation. Actually, I was dreaming of a rosy future! Oh, I think the building must have cost about $100,000, but that left us with only $20,000 or $30,000 of our operating funds. Even the bank told me, ‘You've got a lot of guts.'"

The local reaction to American Honda's presence in the American motorcycle industry was decidedly down. "There is no way that Japan, having lost the war, could produce much of a product," opinion makers would say. "It won't be easy for them to bring something here and sell it." Absolutely no one predicted any sort of success for American Honda.

The American motorcycle industry was then selling 50,000 to 60,000 units annually. It was a market just one-tenth that of Japan's, yet several competitors were fighting it out for a share of the territory. Market expansion simply hadn't yet been considered since, in the U.S., the car was the generally accepted mode of transportation.

Motorcycles were vehicles for outdoorsmen, racing enthusiasts and hotrodders. Most of the motorcycles sold in the market were large, too, with engines displacing at least 500 cc. What's more, the motorcycle had an evil image heavily influenced by outlaws in black bomber jackets, commonly called "Hell's Angels" in reference to the biker society of the same name. Motorcycles had a bad reputation in the American community, and were not embraced by common consumers.

Likewise, the motorcycle industry was thought of as being dark and dirty. Most motorcycle dealerships were dark inside, with oil stains on the floors. This was not altogether inaccurate, since it was common to find oil pans on the sales floor, there to catch the fluid as it dripped from the bikes on display. The atmosphere could be far from inviting.

Selling to America ... with Eight Employees

American Honda began its sales activities in September 1959, with a tiny staff of eight. The company's lead products were the Dream, Benly, and Super Cub (called the Honda 50, in the U.S.), which had just made its Japanese debut. There was nothing small about the monthly sales goal, though. It was immediately set at a lofty 1,000 units.

The thinking was, they simply couldn't grow without adapting their management strategies to the local community. Employees were hired locally, making for a total sales force of eight people, including Kawashima and his subordinate, Takayuki Kobayashi. In truth, the locally hired people proved beneficial to Honda's effort, since they had connections with existing dealers throughout Southern California. Mailings were sent to those dealers, while Kawashima himself visited shops in an effort to promote Honda motorcycles. Moreover, the company ran ads in local trade papers and motorcycle magazines, hoping to entice dealers. Not surprisingly, managers from the dealerships began appearing at American Honda, hoping to test-drive the bikes.

They had been handling American brands like Harley-Davidson and European imports like Norton and BMW, so the Honda motorcycles, with their small frames and strange, boxy features, looked like nothing they had seen before. In fact, many of them thought the product would never sell. Those who test-drove the motorcycles were invariably impressed by their performance, and often they would purchase bikes as examples of Japanese design and craftsmanship.

The decade of the 1950s came to an end just three months after American Honda's sales activities began, leaving the company with a sales record of a mere 170 units. Obviously, it was a far cry from their 1,000-unit monthly sales goal, and it was equally obvious that the road ahead would be neither smooth nor fast.

Problems with the Main Product

The decade of the 1960s was soon in full swing, and amid this new atmosphere of progressivism and possibility - the fabled Jet Age - Honda's monthly sales hit several hundred units.

"It looks like we may be able to do it in America," Kawashima thought, but he was simply flushed with the potential of the moment. For just as he had begun to experience some results, along came the news that problems were occurring with Honda products. Several of the engines in American Honda's main products, the Dream and Benly, had overheated and seized up. In fact, seizing had occurred in more than 150 of them. Mechanics were immediately dispatched from Japan, and Honda went to work in order to deal with the problem. Kawashima knew that a number of the same products were on their way over from Japan to the Port of Los Angeles, so he would have to do something soon. He wracked his brain trying to come up with the answer.

Kawashima's first notion was to have some of the necessary parts sent from Japan, so that the defective products could be repaired prior to sale. He did not want to lose the confidence of his dealers and customers, precisely at a time when business was gaining some momentum. With that, he made his decision.

"As long as we're rooted here in America, we want to be able to sell flawless products with total confidence in their quality," Kawashima said in describing his situation to Fujisawa. "We want to send back all the problem products to Japan."

All units from the same, problematic model lines were then recalled from the dealerships, and product in stock was sent back to Japan. Further, more than 100 units that had arrived at port from across the Pacific were returned without ever being unloaded.

"Had we sold the product back then, after fixing it onshore," recalled Kawashima, "we would have found ourselves with a very bad reputation. Instead, all units were recalled from the dealers and sent back to Japan. Then we started business again with brand-new product. I think the American motorcycle shops were very impressed with our actions."

The motorcycle shops were indeed impressed, applauding Honda for engineering as well as professionalism. After all, they had always believed that any motorcycle on display would drip oil, yet not a drop came from the Honda bikes.

The Motorcycle as Popular Product

Having lost its main products for the time being, American Honda was forced to carry on by placing its remaining product, the Super Cub, in the spotlight. The Super Cub - or, the Honda 50 in the U.S. - was a performance model, featuring twice the horsepower of competing products. Plus, it was small and easy to ride, with a quiet four-stroke engine. The motorcycle appealed to the public as one that was convenient for men and women alike. For instance, the design, incorporating a front cover and wide steps, made it difficult for the wind to lift up a woman's skirt.

The motorcycle's new image was "unlike anything that Americans had imagined before," Kawashima recalled. "It was that of a completely new vehicle; a motorcycle that simply didn't seem like one."

The Honda 50 was also reasonably priced at just $250, making it accessible to a youth market of college students who could buy with their savings or simple-interest loans. Thus, the bike became a viable means of transportation around campus.

American Honda's sales total for May 1961 surpassed the original goal of 1,000 per month. Kawashima, however, was beginning to sense that sales wouldn't grow significantly beyond that point if they continued marketing only through the existing dealerships. Accordingly, with the Super Cub acting as lead product in a new sales network, American Honda launched into a major ad campaign unlike any that the other manufacturers had attempted before. The company would appeal to the public with the message that the motorcycle was truly a popular product.

American Honda traveled places to give presentations on its business plan. It also ran help-wanted ads seeking enthusiastic individuals who wanted to join the motorcycle industry. American Honda did not only just try to expand its sales network, it endeavored to give the American motorcycle industry a shot in the arm. Further more, to make motorcycle shopping more casual and fun, American Honda arranged to have Super Cubs sold at sporting-goods stores and retailers of camping and outdoor equipment.

Eventually it was decided that ads would run in general-interest magazines covering the eleven Western states, and that they would not be limited to trade newspapers and motorcycle magazines. By running advertisements in first-class magazines such as LIFE, the leading American photojournal of the postwar era, Honda aimed to improve the motorcycle's image as a consumer product.

The ads featured bright, cheerful colors and photogra-phs, in considerable contrast to the now-tired image of the outlaw motorcycle. In fact, the word "motorcycle," with its negative connotations, was not used at all. Instead, the slogan "Nifty, Thrifty, Honda -Fifty'" was chosen as a means of appealing to the public's taste for fun, socially acceptable products.

"Running the ads required a considerable amount of money," recalled Kawashima. "I think a color page in LIFE magazine for eleven western states cost somewhere between $70,000 and $80,000. This was after the Honda 50 had started selling, so we decided to be a little bit daring."

The ad campaign worked, and the American version of Honda's Super Cub was a big success. To cope with the increase in customers and an increase in the large numbers of new contract dealers, the staff at American Honda began working to provide a full line of parts and improve its service system.

"Let's put aside the thought of making money with parts for the time being," thought Kawashima. "Let's just make sure we can provide complete afterservice for our customers. Let's not get a reputation for not having parts in stock or not being able to deliver parts in a timely manner." With that in mind American Honda began receiving all service parts via air shipments from Japan, after which the parts were sent to the dealers.

Changing the Image of an Entire Industry

The promotion of sales on a significant level required that American Honda expand its sales network and advertise its products in a manner that was palatable to consumers. And obviously this meant doing away with the negative image surrounding motorcycles and the motorcycle industry in general.

It was decided that all company associates were to wear business suits, and that service personnel were to maintain their work clothes in immaculate condition. In greeting the customer, one would not fail to present himself in a professional, courteous manner with clean, pressed clothes. This message was even stressed to the managers of dealerships handling Honda motorcycles. In addition, documentation was prepared covering sales methods and service techniques, and classes were held throughout the network as a means of educating dealers in the ways of American Honda.

Dealership managers, having been made aware that American consumers found dirty, greasy motorcycle shops very unappealing, were urged to renovate. As an added encouragement, American Honda built its own shop featuring a lot for test drives and a sparkling showroom. It was all part of the effort to wipe out the negative associations Americans had concerning the typical motorcycle shop. Unfortunately, though, Honda's self-owned showroom was eventually shut down, having been found in violation of existing laws regulating manufacturer ownership of dealerships.

American Honda also fostered an environment in which the dealers could devise their own ad campaigns. Top-selling dealers were given subsidies to cover a portion of these expenses, inspiring the shops to compete using a positive, "can do" approach.

It was clear that these efforts would be fruitful. The dealership managers began to involve themselves in promotional activities, and were actively enhancing the appearance of their shops. Many used their money to create an atmosphere that was friendly to women and children, as well as adult male consumers. Others spent their subsidies on advertising to promote their own shops and products. Some even offered their products for use in community volunteer activities.

In November 1961, American Honda held its Holiday in Japan program to invite top-selling dealers and their spouses to Japan. It was one of many events American Honda initiated as part of its promotional campaign.

"Nicest People" Campaign Causes a Sensation

By December 1962 American Honda was selling more than 40,000 motorcycles annually, while the number of dealers - at nearly 750 - exceeded that of any competitor. For the following year Kawashima set a sales goal of 200,000 units, meaning a figure five times that of the previous year's record. It was an astonishing target to the staff at American Honda. Kawashima knew it was not impossible at all, as long as the public reputation of people who rode motorcycles was elevated and the product name became better known. Accordingly, he was willing to invest a fortune on it. In fact, Kawashima was ready to lay down the largest sum his company had ever used to promote Honda motorcycles.

So, when Grey Advertising, a major U.S. agency, proposed a campaign with the slogan, "You Meet the Nicest People on a Honda," Kawashima knew right away that it would work. This was to be a major campaign targeting the eleven western states.

The Honda CA100 made Honda bikes a part of North American culture. The U.S. model differed from its Japanese counterpart, seating two and lacking turn indicators. This model is featured in the “Nicest People” campaign.

The ad depicted housewives, a parent and child, young couples and other respectable members of society - referred to as "the nicest people" - riding Honda 50s for a variety of purposes. Moreover, the colorful illustration and highly professional design appealed strongly to the public. Those who would otherwise have rolled their eyes at the word "motorcycle," and those who previously had no interest in them, soon saw in the motorcycle a new purpose: one of casual and convenient daily transportation.

Mothers who once wouldn't listen to an adolescent child's plea for a motorcycle began to compromise, saying, "I'll buy you one, if it's a Honda." The Honda 50 even became popular as a present for birthdays and Christmas. And with its support from an ever-widening sector of the American public-from students and housewives to businessmen and outdoor enthusiasts-the motorcycle finally won recognition as a popular product.

Grey Advertising, now quite confident in its wildly successful Honda campaign, had a new proposal. "Mr. Kawashima," they asked, "would American Honda like to participate as a sponsor of the Academy Awards broadcast"

The Academy Awards broadcast was a major annual event drawing a public, eager for a taste of glamour and spectacle. Even then the show was televised nationally. Grey maintained that airing a commercial during this program, which attracted 70 or 80 percent of all television viewers, would immediately spread the American Honda name and product line across the nation. The broadcasting fee for two 90-second commercial segments was $300,000. Seen as an outrageous price that would immediately wipe out the revenue from about 1,200 Honda 50s, even Kawashima hesitated before giving it his approval. "When I heard they wanted $300,000, I had serious reason to pause and think about it," Kawashima said, looking back at the plan. "But Fujisawa had always told me that great opportunities weren't so easy to come by. So, I decided to go for it. ‘Let's do it,' I said. But to be honest, I was pretty nervous."

American Honda thus became the first foreign corporation to sponsor the Academy Awards show. And because no one had ever heard of a motorcycle company sponsoring the event, it became a subject of constant conversation among industry insiders and advertising professionals.

But in April 1964 the TV commercial that aired across the country caused an even bigger sensation. The response was simply overwhelming, and people everywhere were clamoring to start their own Honda dealerships. Moreover, large corporations across the U.S. began to inundate American Honda with inquiries concerning tie-ups, including such requests as, "We would love to use the Honda 50 as a product in our sales-promotion campaign."

The Honda 50 had truly succeeded in its appeal to the American public. More than simply another motorcycle, it was seen as a casual vehicle for daily activities, and as such was an entirely new consumer value. It erased the motorcycle's deeply rooted image of evil and discontent. Simply stated, the 50 was a gigantic hit.

"I really think business is a battle that must be fought with a comprehensive array of forces," said Kawashima philosophically. "First, you need to have great products. Then, you need an organization that is appropriate for the product, and people who can make the organization work. In that respect, I was blessed with great products and a wonderful staff. But also, I think the driving force was Honda's decision to build its own sales network. Our direct involvement with the retailers led to the success of our American sales network and sales campaign."

Coping with a Sales Slump in the Mid-'60s

Honda motorcycles soon became a fixture on the American scene, and the sales figure for 1970 passed the 500,000 unit mark. The product line expanded, as well, from the 50 cc Honda Mini-Trail (export version of the Monkey/Dax) to large, high-performance 750 cc road bikes.

It was not easy getting there, however. By 1965, the U.S. was heavily engaged in the Vietnam War. Many young American men, representing the core market for the Honda 50, went off to battle in the jungles of Southeast Asia. Society showed signs of confusion as the financial markets began to wobble, and soon it was difficult to finance even a smaller purchase like a motorcycle. By the spring of 1966, sales of the 50 and other American Honda products were in a nosedive. The slump would continue for some time.

Distress in the American social fabric was commonly perceived as the reason for the slump. Others, however, held a different opinion, saying changes in fashion had diminished the novelty of Honda products.

In addition to a program of price cuts spurred by slashed advertising costs, American Honda began adding optional accessories to its products so that special models could be sold in different styles. Other measures taken to increase product demand included urging the Honda R&D Center to concentrate on the development of new products for the American consumer. As a result, American Honda was able to create a new market for motorcycle sales, launching another product-the Mini-Trail (U.S. version of the 90 cc Hunter Cub) in 1966. This was a motorcycle designed to meet the needs of people who had modified their Honda 50s to ride through wide-open and mountainous terrain.

The Honda Mini-Trail went on sale in 1968, and was instantly accepted as a bike so easy to ride, even a kid could do it. Families everywhere were seen enjoying their Mini-Trails on weekends outdoors.

Moreover, the YMCA (Young Men's Christian Association) hoped to employ the Mini-Trail as a tool to teach young people to actively engage in group activities so that they might grow into responsible adults. The YMCA believed that teaching kids to ride Mini-Trails in a safe and proper manner, and teaching them how to use them constructively, would help achieve this goal. American Honda supported the YMCA concept, agreeing to donate the requested number of thirty Mini-Trails. Additionally, the company provided service parts and accommodated the YMCA's request that mechanics classes be held.

As a result, kids who were not previously interested in YMCA activities began participating, and with great enthusiasm. The YMCA stated, in praise of the Mini-Trail project, that motorcycle activities had also helped prevent juvenile delinquencies. Newspapers and magazines began to feature the YMCA story in large pull-out sections, and these features created a major public reaction.

The program was a great success, and in October 1970, American Honda donated a total of 10,000 Mini-Trails - valued at about $2.5 million - to YMCA chapters across the country. The company's support of the Y-NYPUM (YMCA National Youth Project Using Minibikes) project would indeed continue.

In 1970, American Honda donated a total of 10,000 Mini-Trails to YMCA chapters across the country.

Building a Network for Auto Sales

It was determined that the U.S. could now support a sales network for automobiles. This was a task with the potential to dwarf anything that American Honda had yet attempted.

The N600 model was launched in Hawaii in December 1969, and in May of the following year American Honda began selling the car on the mainland. Through its motorcycle dealerships Honda had earlier established, a sales network for the N600 gradually expanding to include the three coastal states of California, Washington and Oregon.

The N600, the first Honda car sold in the U.S., was marketed through American Honda's motorcycle sales network. In those days, N600s were displayed alongside their two-wheeled cousins.

Nevertheless, the foundation of America's car market was well established, with customers believing strongly that cars should be purchased exclusively from automobile dealers. Thus began the uphill struggle to achieve respectable sales for American Honda's newest offering.

American Honda began building its own network for auto sales in 1973, when a new model, the Civic, went on sale. At first American Honda's philosophy and corporate activities had to be explained to American car dealers, who had for years been aligned with the Big 4: General Motors, Ford, Chrysler, and American Motors. As a result, that effort proved fruitless. The dealers would say, "We were born and bred in this country, and we know the market and customer better than anybody else." They wouldn't even consider displaying the Civic on their lots.

The American car scene, too, was then dominated by extremely large automobiles. The appearance of a new concept in car design-that of a small, fuel efficient and affordable model-was only seen as an act of defiance.

Yet, amid this highly unfavorable situation American Honda began its nationwide search for sales outlets. The company's sales staff, consisting of a dozen people, each took a territory covering several states. Each of them visited the auto dealers in his territory one by one, giving the same sales pitch over and over.

These efforts soon paid off, and the owners of auto dealerships began including the Civic as part of their product lineups. The affordable Civic, however, was nearly always positioned at the bottom of the product list, and was generally assigned to a lonely corner of their outdoor display lot or the used-car area.

Eventually, a turning point arrived in American Honda's auto sales.

From mid-1973 to the following year, the U.S. auto industry found itself reeling under the effects of the first oil crisis. This prompted American drivers to change perception of what constituted value in a car. No longer so content with large, luxurious "gas guzzlers," they began to see the practical benefits of sensible size and outstanding fuel economy.

In 1974, the Civic placed first in a fuel economy test conducted by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). That same year, American Honda began selling Civics equipped with the CVCC engine, the first power plant to pass the strict emissions standards of the U.S. Clean Air Act. Thus, the Civic became America's leader in both fuel economy and low emissions. These qualities, together with its fine performance, helped the car win a broad base of support. Immediately, sales began to pick up.

Satisfaction: Our Own Customers, Our Own Work

"Even if a Honda product were to be the center of attention for a while," said Yoshihide Munekuni, who was then in charge of auto sales for American Honda, "no American dealer will carry Honda on a long-term basis without first understanding and sharing the philosophy behind our corporate activities." Munekuni enlisted the help of J.D. Power & Associates, an automotive research firm, to conduct a survey of every customer who had purchased a Civic through an auto dealer having a sales agreement with American Honda. Beginning in 1976, customer opinions and requests regarding the Civic's general concept and quality, as well as their dealership, were to be collated on a yearly basis.

Munekuni and the staff at J.D. Power arranged and summarized the opinions of the respondents. Opinions regarding the product's concept were sent to the R&D Center as user feedback, while those regarding quality were sent to the factories. Any request that could be answered immediately was given a timely response. Even other issues brought up by the customers were arranged so that they could steadily be reflected in developing and manufacturing the next model.

Opinions and requests regarding the dealerships were also summarized for each dealer using a point system. Subsequently, American Honda's auto sales staff began visiting the dealers one by one, bringing along their files. Based on customer requests, the sales staff and dealers would discuss measures to be taken before the next survey period, making plans for their implementation.

American Honda, too, made a consistent effort to respond to customer requests through its products, working in unison with the dealers to enhance the system of sales and service. Eventually, the dealerships began to trust American Honda. Some began setting up Honda showrooms and putting additional effort into the service department, eventually leading to the birth of dealers specializing exclusively in Honda automobiles.

"CS (Customer Satisfaction) activity did not start out as the neatly arranged program it is today," Munekuni said, recalling the early days of that program. "It was the result of ideas we'd come up with on how we could share Honda's philosophy - satisfying the customer through our work - with the dealers, and how we could have the dealers handle our products responsibly over the long run. We conducted interviews with every individual customer for a span of several years in the hope of providing products and services based on our American customer's requests. By implementing their opinions, we were able to win the trust of our customers and dealers. It was through all this effort that we were able to establish a sales network for American Honda."

The CS program helped bring the Accord to America in 1976, followed by the Prelude in 1979. Honda's user surveys around the world have continually expanded, serving to enhance the entire product line-up.

Moreover, in 1983, the first-ever model created especially for the American market debuted. The exciting Civic CR-X (later sold in Japan as the Ballade Sports CR-X) was developed through the implementation of survey results collected by Munekuni and other's and as a direct response to American customer requests for a car offering the ultimate in fuel economy.

Honda R&D Centers in Japan and in America, in developing the CR-X, applied their considerable expertise in pursuit of a lighter body and a design that would satisfy the American driver. After much hard work, the resulting Civic CR-X by far exceeded the average American car in fuel efficiency (the average for gasoline engine automobiles was around 30 miles per gallon). Achieving efficiency in excess of 50 miles per gallon, the Civic CR-X appealed to American drivers and exemplified the high state of Honda technology.

As American Honda's product line grew, so did the company's reputation among customers and dealers. By 1986, the number of U.S. dealers had passed the 900 mark. In a country where dealers generally handled more than one make of car, the percentage of dealers specializing in Honda cars was more than 70 percent, making it the leading dealership network in America.

Having built a hugely successful network for the sale of widely purchased products such as the Civic, Accord, and Prelude, American Honda now turned to the challenge of building a network that could specialize in luxury cars and high-tech, sporty cars, and thus meet the demands of driving enthusiasts.

The Acura channel was launched in 1986 as American Honda's second sales network. About 60 dealers participated in this program as Honda specialists, selling the upscale Legend and sporty Integra.

That year, Honda placed first in overall customer satisfaction in a nationwide survey conducted by J.D. power & Associates.That was really no surprise, as in the ten years since the start of the CS program in 1976, American Honda had won the confidence of American consumers and grown to become the top auto sales network in the United States.

"Spreading Honda's philosophy in each country through products and marketing, and satisfying our customers through our work," Munekuni said, "is the business of Honda's corporations overseas. Likewise, what I was involved in - selling automobiles in America - represented an effort aiming to satisfy the customer with quality products and dealers. We consistently strove to take that satisfaction level even higher."

American Activities Take Root

American Honda established the American Honda Foundation in 1984 on the occasion of the company's 25th anniversary. In addition to offering aid such as funds for college reserch centers in 1989 the foundation initiated a program to support volunteerism among company employees. Such activities continue to the present day, and are part of the fine corporate citizenship for which American Honda is known.

American Honda started in 1959 with just eight staff members at a location on West Pico Boulevard in Los Angeles. The office was moved to the nearby suburb of Gardena in 1963. In 1990, a new office was completed in the neighboring city of Torrance, with all Honda divisions relocating to the same campus in preparation for American Honda's future growth.

American Honda has taken root amid America'a vastness and inspiring diversity.Employing the philosophy that "profits kindly given to us through local customers must be returned to the commmunity," American Honda has faithfully served as the base for Honda's North American expansion.

The new American Honda headquarters building 100 in Torrance, opened in 1990. In all, eleven separate buildings occupy the same campus.

Note: Honda's employees are also referred to as "associates."