The "Joy of Manufacturing" / 1936

Soichiro Honda was born on November 17, 1906, in Komyo Village (now Tenryu City), Iwata County, Shizuoka Prefecture, as the eldest son of Gihei Honda and his wife Mika. Gihei was a skilled and honest blacksmith and Mika an accomplished weaver. The family was poor but Soichiro’s upbringing was happy, even though his parents were insistent about the need for basic discipline. It was thanks to the thorough education he received from his father that Mr. Honda, despite his freewheeling, irrepressible personality, hated nothing more than inconveniencing others and was always punctual about keeping appointments. He also inherited from his father his inborn manual dexterity and his curiosity about machines.

When Honda was an apprentice at Art Shokai, he assisted the company’s owners, the Sakakibara brothers, in building a Curtiss racer. He accompanied them as their riding mechanic at races, and they won the fifth Japan Motor Car Championship on November 23, 1924. Soichiro Honda is in the center. On the left is Yuzo Sakakibara, the proprietor of Art Shokai, and on the right Shinichi Sakakibara, the driver.

After a while Gihei opened a bicycle shop. Bicycles were at last starting to become really popular in Japan and when people asked Gihei to repair their machines, he sensed a business opportunity. As well as working as a blacksmith he put his natural skills and willingness to learn to good effect, repairing second-hand bicycles and re-selling them at competitive prices. From this moment his business began to be seen as the best bicycle store in the neighborhood.

When he was about to leave higher elementary school, Soichiro Honda saw an advertisement for Tokyo Art Shokai, an automobile servicing company, in a magazine called Bicycle World (Ringyo no sekai). The ad itself was not for bicycles but for "Manufacture and Repair of Automobiles, Motorcycles and Gasoline Engines". Even as a toddler Honda had been thrilled by the first car that was ever seen in his village and often used to say in later life that he could never forget the smell of oil it gave off. So it is easy to imagine that when young Honda saw the ad he immediately decided that he had to work at Art Shokai.

Judged by the number of ads it placed in automobile and bicycle magazines, Art Shokai must have been one of Tokyo’s top automobile repair workshops and there were probably any number of young men eager to become apprentices there. Even though the ad Soichiro Honda saw was in fact not a recruitment ad, he plucked up the courage to submit a letter asking to become an apprentice. There is no way of knowing exactly what he wrote, but in any event it was very fortunate that he received a positive reply.

Soichiro Honda left elementary school in April 1922 at the age of fifteen and joined Art Shokai as an apprentice in the Yushima area of Hongo, Tokyo. Employment in those days was a world apart from what we now expect. Juniors were given board, lodging and a little pocket money, but they received no real wages. Mr. Honda’s books and biographies include many stories about his time at the company but the important point is that his experiences there exercised an enormous influence on his later life.

Enthusiasm for hard work, a quick appreciation of the need to improvise, thinking for oneself, the ability to come up with a wealth of new ideas, a good feel for machines. The owner of Art Shokai, Yuzo Sakakibara, soon spotted the young man’s star qualities and began to take notice of him. Soichiro Honda, too, learned from his boss, not just how to do repairing work but how to deal with customers and the importance of taking pride in one’s technical ability. Sakakibara was the ideal teacher, both as engineer and as businessman. As well as understanding repair work he was also skilled in more complicated processes such as the manufacturing of pistons.

Whenever Honda was asked who he respected the most, he would always mention his old boss Yuzo Sakakibara. It is important to remember that Art Shokai’s repair work included motorcycles as well as automobiles. At that time ownership of automobiles and motorcycles was restricted to a limited social class and most automobiles were foreign-made. Compared to today, there were hosts of automobile manufacturing companies, large and small, all over the world and their output ranged from mass-produced models to high-quality vehicles with small production runs, sports cars and highly unusual collector’s items, all of which were imported to Japan.

All kinds of cars were brought to Art Shokai for repair, making it an ideal place for Honda to work and study, eager – even greedy – as he was in his pursuit of knowledge.

As Kawashima says, Mr. Honda worked so hard to extend and deepen his understanding of automobile engineering that he amazed everyone by the extent of his expertise. He was well versed in every sort of mechanism. "When he was an apprentice at Art Shokai and when he was manager of the branch in Hamamatsu, the Old Man learned so much by doing real work with real machines," said Kawashima. "He didn’t just have theoretical knowledge – he was an expert at all sorts of practical tasks like welding and forging. Those of us who had only studied the subject on paper from an academic standpoint just couldn’t compete."

Sakakibara also encouraged Honda’s interest in the world of motor sports. Motor sports in Japan goes back to the early years of the Taisho Era (1912–1926), around the beginning of World War I. It began with motorcycle racing but soon developed into full-scale car racing, which became popular back in the 1920s.

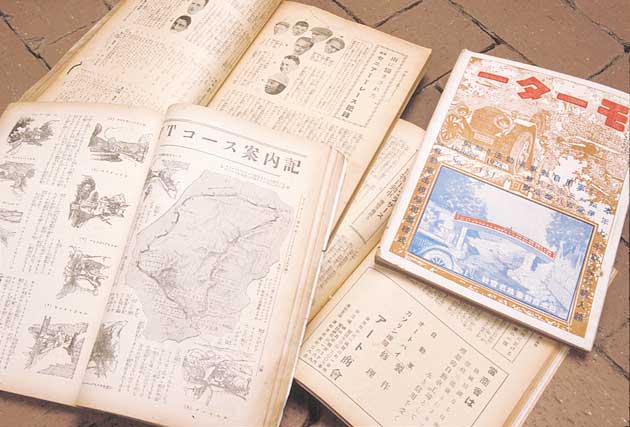

That was not all, because the automobile magazines carried amazingly detailed information about motor sports abroad. Japanese motor racing fans were aware, for example, that the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy (TT) was the world’s greatest two-wheel event, and that the greatest car races were the Grand Prix (GP) and the Le Mans 24-hour in Europe, and the Indianapolis 500 in the United States. Of course, Honda knew this as well.

In 1928, the automobile magazine "Motor" contained an advertisement for Art Shokai that mentions the Hamamatsu branch managed by Honda. The automobile and motorcycle magazines of this period contained detailed articles about the Isle of Man TT Races.

In 1923, the company started to make racing cars under Sakakibara’s leadership with the help of his younger brother Shin’ichi, Honda and a few other students. The first model was the "Art Daimler," fitted with a second-hand Daimler engine. The second was the "Curtiss." This car is still preserved in the Honda Collection Hall in operable condition. This consisted of a second-hand engine from an American Curtiss "Jenny" A1 biplane fitted to the chassis of a Mitchell, an American car. Mr. Honda was particularly keen to help with the development of this special machine, encouraging Sakakibara with his skill in fabricating spare parts. On November 23, 1924, the "Curtiss" took part in its first race at the Fifth Japan Automobile Competition and won a stunning victory with Shin’ichi Sakakibara as driver and Soichiro Honda as accompanying engineer. After that experience the seventeen-year-old Honda would never lose his enthusiasm for motorsports.

At the age of twenty, Mr. Honda was called up for military service, medically examined and found to be color blind. Thanks to this diagnosis he managed to avoid spending any time in the military.

In April 1928, he completed his apprenticeship and opened a branch of Art Shokai in Hamamatsu, the only one of Sakakibara’s trainees who was granted this degree of independence. Mr. Honda was 21 years old and from this moment he devoted himself to making the most of his youth and skill. He was not just admired for his ability to repair machines, but gave free rein to his talent as an inventor, later earning the title "the Edison of Hamamatsu" and starting to do all kinds of work that went far beyond the narrow bounds of a repair workshop.

A photograph dating from about 1935 shows the Hamamatsu works and Art Shokai Hamamatsu Branch Fire Engine, fitted with a heavy-duty water pump. The company also made dump trucks, and converted buses so that they could carry larger numbers of passengers. At the right of the photograph there is a lift-type automobile repair stand, another of Honda’s inventions. Mr. Honda had said that "A human being should not have to do his work crawling around underneath a car" and made the stand himself. The low vehicle at the left of the photo is the "Hamamatsu" racing car and the figure to its right, wearing sun glasses and with a small mustache, is Mr. Honda.

The Hamamatsu branch of Art Shokai around 1935. The car on the left is "The Hamamatsu" and standing beside it with sunglasses is Mr. Honda. Fifteenth from the left is his younger brother, Benjiro Honda. Visible on the far right is a lifting-type automobile repair stand, which was rare then. This was another of Honda’s inventions.

By this time the staff of the Hamamatsu Branch, only one person when it was founded, had grown to more than thirty. Honda’s wife Sachi, whom he had just married in October of that year, joined in running the business, making meals for the live-in staff as well as helping with the accounts.

On June 7, 1936, Soichiro Honda had an accident at the wheel of the "Hamamatsu" in the opening race at the Tamagawa Speedway, Japan’s first racetrack, when he could not avoid hitting another car that was making its way back onto the track after a pit stop. Mr. Honda’s car did a roll and he was thrown clear: He was not seriously hurt but his younger brother and mechanic Benjiro was badly injured, fracturing his spine. Undaunted, Mr. Honda took part in just one more race in October of the same year.

According to Mr. Honda, "When my wife cried and begged me to stop I had to give it up," but she said that the true story was slightly different: "Did he stop because of something I said? I think it was a lecture from his father that made up his mind!"

Times were changing as Japan entered the dark, militaristic chapter of its history. War with China broke out in 1937. During the so-called "national emergency," pastimes like racing were out of the question, and motor sports died out in Japan for a time.

In 1936, the same year the accident occurred, Mr. Honda became dissatisfied with repair work and began to plan a move into manufacturing. He took steps to turn the Hamamatsu branch into a separate company but his investors opposed his wish to start making piston rings. Since he was making good money through his repair work they could not see the need to embark on an unnecessary new venture. Mr. Honda did not give up but sought the help of an acquaintance by the name of Shichiro Kato, and set up the Tokai Seiki Heavy Industry, or Tokai Seiki for short, with Kato as President. He threw himself into this new project and started the Art Piston Ring Research Center, working by day at the old Art Shokai and developing piston rings at night.

Following a series of technical failures he enrolled as a part-time student at Hamamatsu Industrial Institute (now the Faculty of Engineering at Shizuoka University) so as to improve his knowledge of metallurgy. Nearly two years went by during which he worked and studied so hard that his facial appearance completely altered. At last his manufacturing trials were successful and in 1939 he handed over Art Shokai Hamamatsu branch to his trainees and joined Tokai Seiki as president.

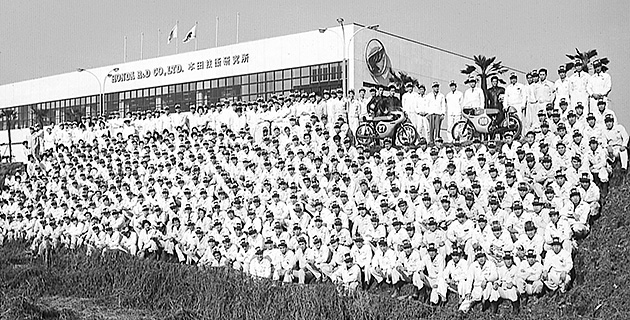

Production of piston rings started as Mr. Honda had intended but he was still beset with difficulties. This time his problems had to do with manufacturing technology. Mr. Honda had a contract with Toyota Motor Co., Ltd., but out of fifty piston rings he submitted for quality control only three met the required standards. After nearly two more years of visiting universities and steelmaking companies all over Japan in order to study manufacturing techniques, he was at last in a position to supply mass-produced parts to companies such as Toyota and Nakajima Aircraft. At the height of the company’s success it employed more than 2,000 people.

However, on December 7, 1941, Japan rushed headlong into the Pacific War. Tokai Seiki was placed under the control of the Ministry of Munitions. In 1942, Toyota took over 40% of the company’s equity and Honda was "downgraded" from president to senior managing director. The male employees gradually disappeared as they were called up for military service, and both adult women and female students began to work in the factory as members of the "volunteer corps." Mr. Honda would calibrate the machines himself and took pains to ensure that the manufacturing process was made as safe and simple as possible for these inexperienced female workers. It was at this time that he devised ways of automating the production of piston rings.

At the request of Kaichi Kawakami, President of Nippon Gakki (now Yamaha), he also invented an automatic milling machine for wooden aircraft propellers. Kawakami was very impressed with Mr. Honda’s ingenuity: Previously it had taken a week to make a single propeller by hand, but now it was possible to turn out two every thirty minutes.

Air raids on Japan became increasingly intensified and it was clear that the country was headed for defeat. As the air raids continued, Hamamatsu was smashed to rubble and Tokai Seiki’s Yamashita Plant also was destroyed. The company suffered a further disaster on January 13, 1945, when the Nankai earthquake struck the Mikawa district and the Iwata Plant collapsed.

This was followed by Japan’s defeat on August 15. The country had undergone tremendous change, and Mr. Honda’s life, like that of Japan itself, was about to be totally transformed.