The Birth of Twin Ring Motegi / 1997

A Passion for Excellence

"We have traveled a long road, a road filled with many obstacles, to finally see the completion of Twin Ring Motegi. The saying goes, 'When you drink water from a well, remember the efforts of those who dug the well.' We could not have accomplished the project had it not been for the people of Motegi-machi and the passion of those at Honda who worked on the project. We must remember that."

On August 1, 1997, Twin Ring Motegi opened its thirteen facilities, including a variety of driving courses such as a 2.4 km oval course, 4.8-kilometer road course, traffic-safety driving training-facility, oval dirt track and north short course (overall length: 1 km). The Honda Collection Hall and Hotel Twin Ring opened in March and April 1998, respectively.

Those were the words of Takeshi Abe, mayor of Motegi-machi in Tochigi Prefecture, who spoke before a large gathering on July 31, 1997, at the opening ceremony of the just completed Twin Ring Motegi. Abe's heartfelt sentiments echoed through the mountains of Motegi, as well as in the hearts of those who were there to share the moment.

"Twelve years have passed since the Twin Ring concept was first conceived," Abe continued. "So, we can honestly say this day would have never come without the efforts of the many who, in eager pursuit of their dreams, devoted more than 4,000 days of work to our project."

Initiative Turns the Tide of Development

In the mid-1980s, when Honda had finally emerged from a period of heated competition with rival Yamaha, the Motorcycle Sales Division at Honda's head office was examining a forward-looking project tentatively known as "Motor Gelände," from the German term for "ski slope." The sales staff's idea was to collaborate with dealers across Japan in creating a nationwide network of facilities where motorcycle users could enjoy riding their bikes, just the way skiers would out on the slopes.

The sales staff were in those days becoming skeptical about Honda's approach. Their concern was whether the company should continue developing new products one after the other and pushing them into the market. After examining various ideas, they decided that what Honda needed was a program that would expand the user base for motorcycles. The new project was their answer to the question, and they were confident that it would succeed.

The sales staff was also responsible for the idea of building independent motorcycle facilities throughout the country. Moreover, they planned to construct one mega-facility; a center of international scale where visitors could also indulge themselves in the enjoyment of cars and power products, in addition to motorcycles. This, they believed, was Honda's responsibility as the source of such products.

This project was approved by the Association of Honda Dealers as a strategy to be implemented on behalf of the national dealership network, and in February 1986, the MT (Motor Track) Project was launched as an interdepartmental undertaking. A team was assembled immediately, drawing on the personnel resources of the Motorcycle Sales Division and Motor Recreation Promotional Headquarters. The team members went on a tour of dealers throughout Japan, describing the project in order to ensure their understanding and cooperation. Thereafter, the dealers arranged suitable sites and began a variety of programs designed to promote motorsports. Soon those sites began holding driving classes, including beginners' classes that featured the use of 50cc motorcycles.

The core facility plan, however, which was to manifest Honda's effort as a socially responsible manufacturer, was making no progress. Masatoshi Suzuki, the managing director and general manager of Motorcycle Japanese Operations, had already proposed such an idea at the Special Management Meeting on Tangible Matters, one of the three special management meetings involving managing directors and board directors. Yet, he had indeed found that approval was not so easy to obtain. Although the executives were in general agreement concerning the concept, they were concerned with the profitability forecasts, which were difficult to obtain despite the sizeable investment needed for the facility. Suzuki, however, was not about to walk away. Along with Yozo Yoshida of Motor Recreation Promotional Headquarters, the MT Project's secretary-general, he attended numerous Special Management meetings, always with significant refinements designed to resolve problems the executives had previously pointed out. The two men shared a passion for the project, and were determined to make it a reality.

Top management, including Company President Tadashi Kume, had decision-making power, but was reluctant to give Suzuki and Yoshida an unequivocal "no." Still, they had become increasingly pessimistic about the commercialization of society at large. They were afraid that people would soon lose their "love" for motorcycles and cars, and instead begin to think of them as mere tools. The management felt Honda needed something new - something that would nurture aspirations - in order to create a progressive car culture and raise the level of morale among company employees.

Corporate Ideals: Keeping the Faith

The list of viable sites for the core facility of the Motor Gelände Project had so far dropped to seven, but Yoshida and other team members continued visiting the candidate properties in their workboots, studying their respective areas in detail. What they found was that each site had distinct advantages, as well as certain disadvantages. It would be hard to pick just one.

Yoshida had served as a secretary to Soichiro Honda until just two years prior to the start of the MT project, and therefore felt it would be a good idea to consult him about a possible selection.

Mr. Honda encouraged Yoshida, saying, "I have to leave decisions regarding basic plans to the executives. However, what you decide now is important, since it will influence the planning. So, make sure you buy enough land."

The company founder's words were precious to Yoshida, because he had witnessed with his own eyes the pain and anguish Mr. Honda went through in establishing his cherished Suzuka Circuit.

Yoshida went to see a big supercross motorcycle-racing event at Jingu Baseball Stadium in November 1987. As he sat there watching the race, he realized an important thing: Although the bikes were rocketing up and down around the course, sending a roar of noise through the stadium, the sound seemed to be contained within the building.

"The sound is being dispersed upward due to the stadium's conical shape." It was thus clear to Yoshida, once he had discerned the reason for this, that one site among the candidates would offer a similar advantage. He was convinced that the Motegi location, which was surrounded by mountains, would have the effect of limiting noise infiltration to the outside.

The site, located in the eastern district of Motegi-machi in the Haga Gun of Tochigi Prefecture, covered an area of 6.6 million square meters that could comfortably hold three Suzuka Circuits. In addition, it was relatively near to Tokyo. The direct distance, was only around 100 kilometers, so people from the city could go there by car in only two hours. Soon, Motegi-machi was chosen as the site for Honda's MT Project.

Having learned of the decision, Vice-President Koichiro Yoshizawa went to visit the site. Yoshida accompanied him as a guide. After all, Yoshizawa, who had once worked at Techniland (currently Suzuka Circuit Land), was not content simply to listen to information given at management meetings. He simply insisted on seeing it himself. As their car drove through the streets of Motegi-machi toward the site, Yoshizawa found that neither of the two access roads was in sufficiently good condition. Moreover, he noticed that the site was covered in a random overgrow-th of trees, and that it was located on a low promontory of land within the hills.

"We'll definitely need a lot of money in order to develop this land," Yoshizawa said. "It may be difficult to recover our investment within just a short time. Instead, we should take a long-term view - a very long one. But it is feasible, I believe. Suzuka [Circuit] is a place where spectators can see professionally run championship races. If this one is to be a participation facility for the visitors themselves, we should minimize the cost of the facility."

"We'll make it happen," Yoshizawa continued. "In addition to organizing and promoting racing events, we must satisfy our customers in their hearts (by satisfying the desire to participate in motorsports). That's the principle at Honda. We can expect the synergistic effect of two unique advantages: first, being in the motorcycle and automobile businesses; and second, having circuits in the east (Motegi) and west (Suzuka)."

Yoshizawa, standing there at the site in Motegi, had made his decision.

The project's final management meeting was held March 31, 1988, at Honda's head offices in Aoyama. There was a consensus among the executives, who wanted to give the project a green light. However, they could not make such a decision hastily, since it was clear that it would be quite difficult to turn a profit. Amid round after round of discussion on various related issues, one of the participants made a particular comment.

"How can Honda remain Honda if we can't realize a dream of this scale?" the person asked. That comment completely changed the meeting's atmosphere. It was also a wake-up call to Kume, who remembered, "To pursue dreams and share the joy: This was Soichiro Honda's ideal. He has shown us through his words and actions how important it is to carry through this ideal and not be blinded by short-term profits. That became Honda's corporate ideal, and has remained so to date. So, I have the responsibility to keep this ideal alive...." Kume had made up his mind.

"I want you to work on this project from a long-term, international perspective," Kume announced. "I want you to create a facility of ample scale that can foster our dreams." With this resounding note of determination, the meeting was officially closed.

Following the management meeting's official approval, the MT Project was reorganized as a corporate endeavor. With Suzuki and Yoshida appointed as Large Project Leader (LPL) and acting LPL, the new project team went to work. Three years had passed since Suzuki and his colleagues first proposed the idea at the Special Management Meeting.

Fostering the Ties of Trust

Abe learned of the Honda project in the summer of 1987, soon after he was elected mayor of Motegi-machi. When he received a phone call from the governor and was told that Motegi-machi was one of the candidate sites, Abe replied without hesitation that he wanted to bring Honda to the town.

Motegi-machi was at that time one of Tochigi Prefecture's municipalities officially designated as an underpopulated zone. To make matters worse, the town had during the previous year been deluged by a flood of unprecedented scale, sending turbulent streams through the downtown district. These streams had effectively washed away 80 percent of that area of town. Abe was indeed looking for something new; something that could form a core of the town. Therefore, Honda's proposal to build a large-scale leisure facility on hilly land in the town's lower river area was an offer he could not ignore. He was also confident that the project would win the support of town residents, who were also concerned about the community's future.

Following the receipt of a proposal from Honda, Motegi-machi proceeded to hold a town-council meeting on April 15, 1988. The council membership duly recognized the project's potential benefit to regional revitalization, and therefore decided to treat the proposal as a case of enterprise attraction. It was their consensus that the town would provide support for the project. On December 9 of the same year, delegates from Honda, including Senior Managing Director Tetsuo Chino, Suzuki, and Yoshida, visited the Tochigi Prefecture Political Journalists' Club and announced the establishment of their tentatively named Mobility World Motegi Project.

The following points were made in their press statement:

Honda has long been implementing programs to promote safe driving and broaden the horizon of motorsports. The facility planned for Motegi promises to expand our activities even further in that regard. It will also become the center of a worldwide mobility culture, equipped with computer-controlled field-sports facilities and amenities that will allows visitors to appreciate and enjoy their time outdoors.

Yukihide Maruyama and Isamu Watanabe, who had been assigned to the project from the General Affairs Department, began a series of explanatory meetings two weeks after the official announcement. These were attended by Mayor Abe, as well, in order that he might help convince a group of nearly 400 local landowners.

Watanabe suspected they would not have much difficulty persuading the landowners, because Honda had for years been doing business in Tochigi Prefecture. However, his hopes were left shattered at those first few meetings. The landowners suspected that the project was merely a disguise shielding Honda's plan to build a treatment facility for industrial waste.

The landowners, having listened to the explanation, expressed considerable concerns.

Maruyama explained:

Honda has no intention whatsoever of building a facility such as the one you suspect. What we want to build is a facility that will exist in harmony with nature in Motegi-machi, and to make you and many others happy and thankful. We will consult you on issues that will emerge along the way. We want to work together with you to bring this facility to life in its most ideal form.

Maruyama and Watanabe set as their first objective a trusting relationship with the landowners, committing themselves to the process no matter how long it would take. They were prepared to fight a long battle. Subsequently, they spent several days commuting between Tokyo and Motegi-machi. On the evening of a regular meeting day, they would depart the head offices in Aoyama, conduct explanatory meetings at the town halls of Motegi-machi's six local districts, then return to Tokyo via the last scheduled bullet train.

Thanks to efforts such as these, the number of landowners who were agreeable to selling their properties had thus grown to 60 percent. In fact, it climbed to more than 80 percent following the tour at Suzuka Circuit, where they were given a chance to see motor sports in action. Then, in August 1989, the final land-acquisition price was agreed on at a meeting with the landowners' representatives. The acquisition agreement was executed and became effective in December 1990.

The conclusion of the agreement, however, had brought forth a new concern, and it continued to bother Maruyama and Watanabe for quite some time. They were afraid Honda might not be able to purchase all the land that it required for the project. A refusal by even a few of the 400 landowners would create holes in the construction site, making it impossible to build a large-scale facility. Still, they were determined to maintain open and fair negotiations. They never approached the landowners individually in an attempt to strike a quick deal. Watanabe thought of Sayama Factory (currently Saitama Factory's Sayama Plant) where he had once worked, and where he had seen his colleagues go through such suffering simply trying to cut costs, even by as little as one-tenth or two-tenths of a yen. Knowing that their precious funds came from the sweat and determined effort of so many employees, Watanabe did not want to spend it irresponsibly. In fact, more than anything else the two wanted to maintain the trusting relationship with the rest of the landowners. They had no wish to damage the clean image that their predecessors at Honda had tried so hard to build.

It's Your Dream. Don't Ever Give Up!

The times were changing dramatically, though. Following the crash of the stock market in February 1990, the Japanese economy went into a rapid downward spiral, which was all the more devastating after such a long period of growth. Actual growth in the GNP had slipped into the negative territory and personal consumption had slumped as well, resulting in a decline in domestic auto sales. Like many other companies hit hard by the recession, Honda had found itself at a critical juncture.

Under the circumstances, it was natural that the MT Project would be under such pressure. After all, the budget for the project was equivalent to the entire net profit of one fiscal term at the time. Moreover, critical perceptions had emerged at management meetings, where the progress of the project was reported. The board members raised tough questions such as "Why don't we squeeze the budget," and "Can we postpone the plan?"

Zen'ichi Mabuchi, then the project's acting LPL, would sometimes lose his appetite for words during such heated exchanges. However, despite the criticism, Senior Managing Director Nobuhiko Kawamoto remained a staunch ally, speaking out in the project's defense. This was because Kawamoto himself held the opinion that Honda should not be only a manufacturer of products but also a company that could provide an outlet for people and their aspirations.

Kume retired in June 1990, and Kawamoto became the new company president. Therefore, with the change in management the company began searching for ways to revitalize the organization. Based on an idea raised at the board meeting, it was decided that Motegi would be used to inspire the employees. They would begin with a company-wide contest in order to seek out the most creative ideas for Motegi. In August, a large poster was put up on the bulletin board at all factories and offices, reading, "Wanted: Adventurers of the Heart. If interested, contact the MT Development Planning Office. We promote the establishment of Mobility World Motegi." The purpose of this poster, obviously, was to recruit project members within the company. The said project members could then take on specific tasks for the project, employing a budget of several tens of billions of yen. The idea contest and recruitment poster had thus made "Motegi" a familiar word among Honda employees.

Two hundred and twenty employees replied to the ad. All were brimming with enthusiasm at the opportunity to help bring Honda's dream to life. After sifting through essays on themes such as self-introduction and reasons for applying and a long series of interviews, seven male and three female applicants were finally appointed to the project membership. With that the newly expanded team of 25 persons, each with experience in different functions, began reviewing the mountains of ideas submitted by the employees, trying to find the most interesting and original plans. Various possibilities were considered under the theme of "mobility on land, on the sea, and in the sky."

February 1991 saw the establishment of Honda Mobility World Co., Ltd., with capital of 100 million yen as a joint venture with Suzuka Circuit Land. As a result, five associates of Suzuka Circuit Land, each an expert in a specific field, joined the project team.

The established schedule had stated that construction would begin at Motegi in July 1991, in time for an opening in April 1994. However, it was beginning to look as if the schedule would be delayed more than two years, since the layout had to be changed in areas where the landowners remained in opposition to the sale. Thus, Honda was required to conduct another round of environmental impact studies regarding birds, insects, and plants, in accordance with the regulatory requirements of Tochigi Prefecture. The new studies had to be completed by early June 1992. This meant there would be a significant delay in the issuance of permits for development.

At that point, speculative articles were published in newspapers and other media, featuring such headlines as "Honda to Join Others in Canceling Project?" After all, the country had just seen its bubble economy collapse after 53 months of continuous growth dating to December 1986. As a result, the thirty or so construction projects for racing facilities across Japan were falling by the wayside one after another. Soon, the residents of Motegi-machi were very concerned about the future of their project.

One evening Mabuchi was called by the town's deputy mayor. "Please tell me the truth," said the gentleman, pressing Mabuchi for an answer. Mabuchi, however, replied without hesitation, "We have no intention of canceling the project. Please be assured and give us your support, just as before." Separately, Maruyama and his staff had been attempting to calm the landowners by saying, "Should the project be canceled, it is because Honda has gone under."

Another problem had also reared its head. When a public hearing was held concerning the environmental impact study, several residents who had moved from cities voiced their objections. Claiming the project would have a damaging effect on the environment, they began an organized protest. Many Motegi residents were stunned. Trees need nurturing to grow, they said. They need people to remove the weedy undergrowth and prune away dead branches. However, Motegi-machi was no longer able to provide that care. To the landowners and other residents, the narrow-minded protest that ignored the town's bleak realities was completely off base. However, the protest caught the attention of the media, in light of growing public sentiment regarding the environment. Therefore, Mabuchi got busy with the reporters and journalists. It seemed there was nothing moving ahead on schedule.

The MT Project team was also concerned about the future of their endeavor. They had formed four groups in order to study project themes and plans regarding "Motor Gelände," "Do Sports," "Natural Recreation" and software development. However, it was frustrating to examine ideas for a project when one was unsure whether the project would really survive. Agonizing days continued while they waited for an answer. Although the team had not been told of a cancellation, they could certainly perceive the difficulties in the situation. The department's budget was slashed in half, and many other Honda events such as idea contests and NH Circle World Meetings were canceled. Expecting the worst, the team devised a contingency plan that called for considerably shorter courses, no bleachers for an audience, and an unpaved parking area lying on bare ground. Still, in their hearts, they were shouting, "We don't want to give up. We will not surrender!"

Passion Brings Down the Walls

As the budget of 38 billion yen gradually became a reality, numerous plans were integrated under the MT Project, all based on two themes: motorsports and safe driving. Using the keyword "people," the team set out on a quest for ideas that would propel the new facility into the 21st century. As a first step, they decided to study examples from the U.S., where motorsports were thriving as a modern entertainment industry.

Hajime Takakuwa flew to the U.S. in May 1993. Takakuwa, who had been assigned to the project from Suzuka Circuit Land, was designing race courses at Motegi. When he went to see a NASCAR Race in Charlotte, in the southeastern state of North Carolina, he was amazed. Though the day's program was only part of a two-week event, the circuit was filled with at least 100,000 people. He could hear them cheering and shouting, and to an extent he wondered why.

"What a huge crowd," he wondered. "But why? What's different about this event?"

Takakuwa studied the circuit carefully, until something significant became apparent. It was the design of the stands, which allowed the spectators to follow the entire race with their own eyes. Takakuwa knew that with road-racing courses people in the audience could see the machines blast by for only a brief moment as they zoomed along the stretch of pavement in front of the seats. By contrast, at the oval course where the NASCAR race was held, the spectators could watch every move their favorite drivers made, from green light to checkered flag, and all from the convenience of stands overlooking the course.

Takakuwa subsequently visited Indy races, midget-class races and various other events in the U.S. Each time he was amazed to find that the races had been produced as a form of audience-participation event. Through interviews with dozens of circuit staff and officials, he learned that, an ideal oval course should be 2.4 kilometers long, in order to let the audience feel the excitement of high-speed racing, which of course was the key appeal of oval-course competition. Above all, Takakuwa realized that the spirit and concept of motorsports in the U.S.-notably the ways such races were produced and enjoyed-was something very different from what existed in Japan.

"No matter what, I want to introduce the American trend in motorsports to Japan," Takakuwa thought. Therefore, immediately upon his return to Japan he drew up report after report detailing his findings with regard to the American racing world. Then, in October of that year, Osamu Kobayashi, who had at one time headed the Public Relations Department and Motor Recreation Promotional Office, was named acting LPL on behalf of the project.

"You must make sure the facility sends a message from Honda. This will be our gift to the 21st Century," Kawamoto told Kobayashi. Kobayashi was inspired by those words, and was proud he had been given the responsibility of such a project. Indeed, he thought, MT was the very essence of Honda's corporate culture.

Kobayashi began an exhaustive review of the plan along with Takakuwa and other staff members. They did not want to build a facility that would simply be thought of as Japan's ninth road course. Instead, they envisioned a facility equipped with an oval course and a wide range of amenities for the participation of motorsports enthusiasts and leisure spectators alike.

Several months later, the authorities of Tochigi Prefecture were ready to issue a development permit based on the revised layout submitted a year earlier, which reflected the partial changes necessitated by the missing parcels of land. Even though time was not on their side, the team did not want to compromise the project's guiding concept. This was their last chance. The issues were discussed every day from every possible perspective, and a process of trial and error was initiated in order that a means of achieving their goal could be identified. At the same time, Kobayashi met with each of the company directors comprising the management team, taking them out to the construction site in Motegi and discussing the dream he knew Honda should pursue.

Based on the results of numerous studies carried out under the MT banner, numerous management meetings were held to decide whether or not to build an oval course. Nobuyuki Otsuka, senior managing director and chairman of the Special Finance Committee, whose task was to review and establish profit/fund strategies for the Honda group, made several trips to Motegi. There he examined the concept and future prospects as outlined by the team. Through that process, he came to realize that the company must be prepared to spend 60 billion yen in order to complete the project as planned.

Net profits for the fiscal 1992 term amounted to 30 billion yen. The forecast for 1993 was less than inspiring, at just half that figure. There was no way such an enormous budget could be approved. On the contrary, the company was under pressure to implement a corporate restructuring in order to ensure the flexibility and strength needed to overcome difficult times ahead. Otsuka, however, continued in search of ideas that would keep the project alive. He was well aware of the previous president Kume's desire to realize the project, as well as the current president Kawamoto and the many others behind the project. All of them wanted to create a symbol of Honda's corporate culture. Otsuka had no wish to extinguish the flames of such a great collaborative effort.

Otsuka at last concluded that the 40 billion yen needed to keep the project running for a while didn't have to be paid out as a lump sum. Even if the project was ultimately to require as much as 60 billion yen, the facility could be expanded gradually over the course of a decade or more. With that in mind, they had only be expending around 5 billion yen each year. Therefore, Otsuka decided that although the company was in deep financial trouble, Honda would be able to come up with the money using funds on hand.

A management meeting was held February 1, 1994, to finalize any issues that had so far gone undecided, such as the building of an oval course and associated site work, which had already been scheduled. Kawamoto and Otsuka, sitting side by side at the meeting, murmured to each other continually. A concerned Kawamoto kept asking, "Can you do this?" to which Otsuka would consistently reply, "Yes, we'll be able to accommodate it." The meeting eventually concluded with approval of the plan, which called for a race course facility offering both road-circuit and oval tracks. Coincidentally, 1994 was also the year that had been established for Honda's entry into the competitive Indy Race Car circuit, and this was to work very much in favor of the MT Project. Approval, however, was granted on the condition that the tracks and visitor accommodations be built at a final cost of less than 43 billion yen, and that the entire facility open by the end of 1997. Since Tochigi Prefecture had on January 27 issued a development permit based on the original plan, preparation of the site was able to begin as early as mid-February.

The name of the operating company was subsequently changed to Twin Ring Motegi Co., Ltd., and the project name became "Motegi Project." Lengthy discussions were held in which project members examined how they could meet the conditions of approval given at the management meeting. Thus, it was already July when the final course layout was decided and the request for changes regarding the oval course was submitted to the offices of Tochigi Prefecture. However, the last-minute change was met with anger among the regulators, who were furious that Honda would have made such a drastic change in plans within just a few months of the development permit's issuance.

The team was not about to give up, though. Convinced that the dual-course design was what was needed to make Twin Ring Motegi a racing facility for the 21st Century, Kobayashi and his colleagues visited the prefectural offices repeatedly. To show their utmost respect, they bowed to every official they met in the hallway. Motegi-machi's Mayor Abe even lent as much support as he could. Ultimately the officials came to understand the need for such changes, seeing that the prefecture as a whole would benefit from the presence of a world-class venue rather than Japan's ninth road course. Thus, when at last the regulators filed their request for processing, the streets of Motegi filled with Christmas jingles.

Kawamoto announced the specific plan of Twin Ring Motegi in January 1995 at the company president's New Year's press conference.

A Constant Search for Challenges

Another core purpose of Twin Ring Motegi was its safe-driving facility. Again, just as they had done on behalf of the racing section, the team went through a series of discussions in an attempt to integrate original ideas with Honda's expertise in safe driving, which the company had accrued through three decades of effort in the field.

The active-safety training park employs an in-ground sprinkler system that helps teach emergency-avoidance skills. This is just an example of Motegi's various training facilities, where students can safely experience the dangerous conditions they may encounter during normal, everyday driving.

Students on the midget car track (top) can learn the basic driving skills of often-dangerous oval-course racing, yet do so safely and enjoyably. The Side-by-Side track (bottom) lets fans experience the excitement of Formula Car racing. The key feature of Twin Ring Motegi is the variety of facilities designed to let participants enjoy these experiences in a realistic manner.

Koji Kimikobe was on assignment with the project in order to contribute his experience at Suzuka Circuit's Traffic Education Center. However, each plan he submitted was turned down by Masayuki Yoshimura, who as administrative head of the Office of Safe Driving Promotional Operations was acting as an adviser to the project. Yoshimura would criticize his every plan with comments such as, "This isn't interesting at all. Why must you simply repeat what we've been doing for nearly thirty years? Your plan is of no use unless it has something that clearly differentiates it from the ordinary approach."

Yoshimura was proud of Honda's achievements in creating the basis of modern driver-safety education in Japan. However, he also had critical views as to how Honda should establish its direction in the field, in anticipation of the 21st Century. To Yoshimura, there was absolutely no point in creating a facility for driver-safety education at Motegi unless it could ensure the attainment of a new goal. Therefore, in June 1996, Kimikobe flew to Germany, the home of such prominent automobile manufacturers as Porsche, Mercedes-Benz, and Audi, in order to study trends in driver education. At the training centers in Sachsenlink and Nurenberg, Kimikobe was astonished to learn that common-sense thinking in one country would not necessarily be accepted as such elsewhere. For example, safe-driving classes in Japan were generally considered a kind of disciplinary punishment, given that such education was usually imposed on repeat traffic violators. Their German counterparts, though, had a much more positive association, being a kind of reward for demonstrated excellence on the road. Much of the curriculum was exciting and dynamic, eliciting a sense of eagerness among students. One training method employed a device resembling a record turntable, with which the student could experience the sensation of slipping as he or she drove over it.

Talking with personnel from the training centers, Kimikobe learned that such classes were designed to let the students experience, albeit safely, the dangers they might encounter in Germany during the long winter, or through the course of their travels along the country's hilly roadways. Thus, a new concept was defined following Kimikobe's trip to Germany. Instead of simply being forced to learn, the students at Twin Ring Motegi could be encouraged to learn through the use of proactive and participatory techniques.

Based on the report that Kimikobe wrote after his trip, a new concept was defined for the safe driving education facility at Twin Ring Motegi. The new concept endeavored to create a school in which students could experience the dangers of driving in a safe, fun manner, using scientific equipment. To accomplish it, the team continued the examination and refinement of ideas.

Ultimately. the plan incorporated a range of facilities that employed highly advanced construction technologies. Among the many notable examples was a course with a low-friction surface equipped with a device that momentarily shifts parts of the road surface to the left or right, creating a quasi-skidding condition.

Sharing the Dream

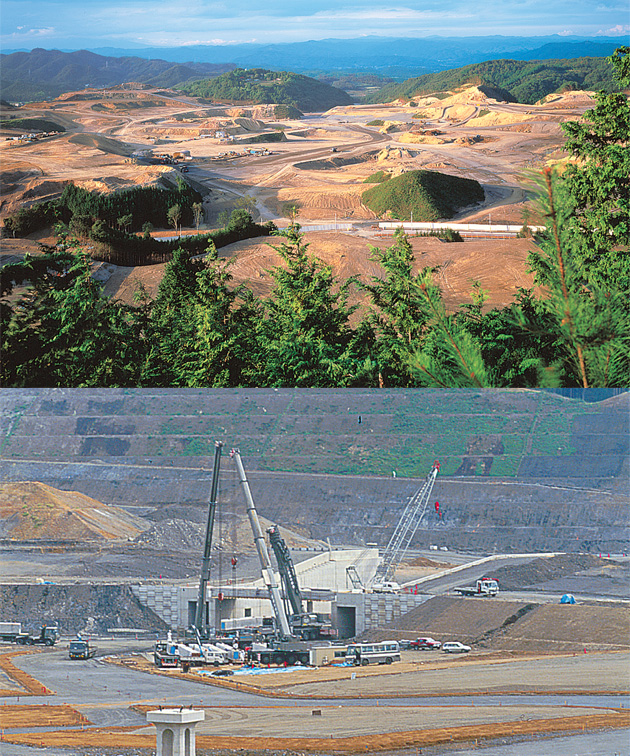

Twin Ring Motegi's construction, which required that hills be leveled and lowlands be brought up to grade, was to be the largest construction project in Japan ever financed by a single, private company. The magnitude of work involved in improving 640 hectares of land (137 times greater than the Tokyo Dome indoor baseball stadium - which required moving 1.3 million cubic meters of earth by volume and redistributing it to raise the level by as much as 65 meters - was equivalent to the construction of the New Hiroshima Airport. Motegi-machi, whose population was a meager 18,000, suddenly found itself playing host to 800 construction personnel, 280 trucks, and seven 70-ton dump trucks with giant tires 2.7 meters in diameter. During the construction, many strict rules were in force on behalf of environmental protection. For example, any vehicle leaving the construction site had to have its tires washed with water so that they would not soil the nearby roads. Furthermore, in addition to preserving 60 percent of the trees present at the site, the water systems, mountain ridge lines, and other natural features were left unaltered. This was done in order to retain the natural landscape of the surrounding area. The nanophya pygmaea, a rare subspecies of dragonfly that propagated in marshlands that prior to Honda's acquisition had been used for agriculture, were transplanted and preserved with the help of local scientists. This, in fact, was the world's first successful transplantation of the nanophya pygmaea.

Based on Twin Ring Motegi's conical design, a massive amount of work was conducted in order to level the hills and raise the ground by as much as 65 meters. Concurrently, the project's environmental impact was carefully studied and 65 percent of the trees on the site were preserved as a means of mitigating the environment.

The site was even open to visitors during the long period of construction. Kobayashi met with every group of people who came to see the site, and carefully outlined Honda's reason for creating the facility. By the time it was complete, the total number of visitors had gone well past the 15,000 mark.

Hard work and consistent effort had made Twin Ring Motegi a familiar name in Japan, even before its official debut. Even the architects, structural engineers, and construction personnel of Nihon Sekkei, Dainihon Doboku, and Nihon Hodo - the project's subcontractors - learned to share the Honda vision as they listened to Kobayashi's enthusiastic descriptions of what the facility would offer. Of course, these professionals faced numerous difficulties of their own at Motegi. For them, there was considerable work involved in overcoming obstacles. With their help, though, Twin Ring Motegi became the first construction project in Japan to apply GPS to mounding control. This made possible a high degree of accuracy in measurements, using satellite-based signal technology.

The site preparation was finished at last, and with considerable precision, without the need to carry out excess earth or truck in additional backfill. As a result the land-subsidence ratio at Motegi was a mere 0.3 percent. Another example of engineering excellence is the connecting link over the oval course, the core feature of Twin Ring architecture. This beautiful bridge - actually greater in width than length - is virtually impervious to vibration, remaining stock-still even as a crowd of racing machines hurtles beneath is at speeds of 300 kilometers per hour.

The collapse of Japan's fabled bubble economy, at first a threat to the very existence of the project, gradually became a tailwind that served to push the project forward. The recession brought down rental charges for large construction machinery, as well as the costs of various construction materials to a point well below the original estimates. This created an unexpected surplus in a budget that should have been barely enough for the race tracks alone. The extra money was used to build stands for spectators. There were, in fact, few other surprises along the way, except for a delay caused by the hotel site's discovery of 1,200 boxes of straw-rope pottery dating from the mid-Jomon Period. Thus, in all, the work ran very smoothly.

Cultivating a Field of Dreams

Chairman Andrew Craig of CART, the organizing body in charge of the Indy Car Race series, visited Twin Ring Motegi in March 1996, while it was still under construction. "Are you crazy?" Craig said, clearly awestruck by the scope of construction. "It looks as if you're building a dam." However, he followed that remark with an expression of high hopes for the project. "We want to bring our race to Japan," he said, "just as we've done in Brazil and Australia. And we'll see it happen right here." Craig could not have been more correct, for in November of that year an agreement was signed to hold Japan's first Indy Car Race event in the spring of 1998 at Twin Ring Motegi.

Japan's first Indy Car Race was held in March 1998 on the oval course at Twin Ring Motegi. The race brought all the thrills and excitement of the famed American motorsports to an all-new, world-class venue.

Forty-five enthusiastic people joined Twin Ring Motegi in April 1997 as the new company's first employees. The grand opening was drawing near, and the recruits would have to do their very best in order to prepare for it. Then, on July 31, more than 2,000 people including, the landowners, local residents, government officials, construction personnel, and staff and representatives from Honda, gathered at Twin Ring Motegi.

Kawamoto spoke before a large audience following the cutting of the tape:

"Twin Ring Motegi is surrounded by a great abundance of nature. Let's make it a creative place with an eye toward the values we hold dear, in trust for the future. It will be a meeting place between people and vehicles, people and nature, and people and people."

The project team formed in February 1986 was dissolved on October 1, 1997, when Twin Ring Motegi Co., Ltd., began full-scale operations. In March 1998, Japan's first Indy Car Race was held on the oval course there. A crowd of 55,000 cheered as this classic American motor sports got under way, galvanizing them with thunderous sound, awesome speed, and the constantly changing positions of professional drivers.

A great series of plans had thus been brought to life by the employees of Honda at a place known as Twin Ring Motegi. These included the opening of the Honda Collection Hall and Hotel Twin Ring, along with the introduction of the Side-by-Side Formula Car beginners' track and ICVS futuristic traffic system. Today, Twin Ring Motegi continues to evolve as a giant mobility park that mirrors the possibilities of the future.

A goal is established beneath a great and inspiring dream, and with determination the people of vision strive toward that goal in order to realize the dream. This is the spirit of Honda; a spirit of endeavor that has been kept alive for fifty years.

Without that spirit, a project the size of Twin Ring Motegi would have quickly overwhelmed any effort to conquer it. Today, Twin Ring Motegi stands as a new mission for the next generation of Honda employees to fully and earnestly utilize a facility to mark the 50th anniversary of Honda's founding.

Twin Ring Motegi is a field of dreams where dreams are sown and nurtured. It is truly Honda's gift to the 21st century.