The ME Engine (G100 / 150 / 200 / 300 / 400 Series) / 1977

Reviving the Power Products Business

Honda began manufacturing power products in 1952, just four years after the company was founded. Naturally, motorcycles created a technological base for those power products. For example, the company's first general-purpose engine, the Type H, was a modified version of the Type F engine used in the Cub. Therefore, in a way the company's new business in power products was propelled by technology acquired through the manufacture of motorcycles.

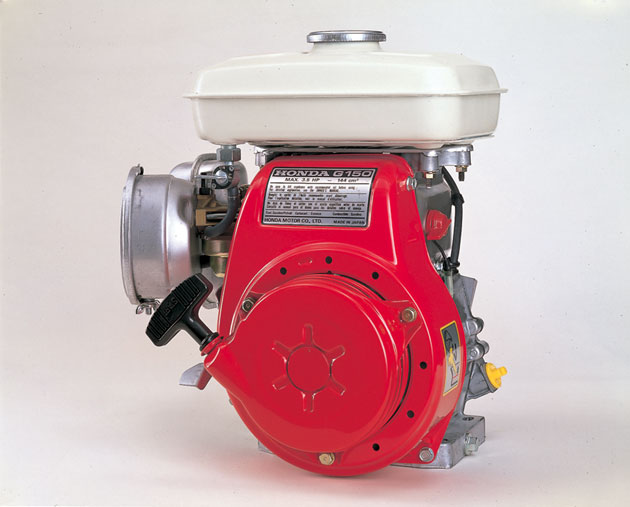

The ME engine series, G150

The road to success in power products would not be easy, though. While Honda was already enjoying a reputation as a premier maker of motorcycles, it had no experience with power products. Moreover, the value the customers looked for in power products varied according to their particular applications. Added to that was the fact that many more types of power products had to be manufactured in order to satisfy market expectations. These elements combined to create a far more complex business than the one involving motorcycles. A key aspect of the business is that power products are generally divided into two categories: engines and complete machines. Accordingly, how a company might operate can vary depending on the category. Engines are supplied mainly to OEM companies as single units, while complete machines include a range of end-user products such as tillers.

Motorcycles and cars are like complete machines. Ever since the 1959 introduction of its F150 tiller, Honda had focused on complete machines. There was a strong conviction that the significance of being in that business was the ability to build and sell complete machines. With complete machines, Honda could satisfy its customers directly. However, along with that came various points of feedback from Honda customers. Listening to that feedback would lead to new products and technologies.

General-purpose engines, on the other hand, are supplied to OEM companies, so it is difficult to relate those products to their end users. The staff involved in the development of Honda power products had a definite sense of passion for their work.

They would not be satisfied with just making general-purpose engines. Therefore, it was natural for the company to focus on complete machines.

Another challenge inherent in power products is that the manufacturer must offer a range of models for each product in order to meet different needs. If it fails to do so, the manufacturer cannot meet customer expectations or sustain its retail operations. This applies to all work machines, including agricultural equipment, power generators and outboard marine engines, necessitating the small-volume production of multiple varieties. For these reasons Honda required a certain amount of time to build sufficient strength in the areas of development, cost competitiveness and marketing, in order to compete in the marketplace.

Honda's struggle to develop and market complete machines continued for two straight decades. However, as long as it remained in business the company would not be satisfied with less than absolute performance. As the 1970s began, there was a thirst throughout the organization; a hunger for the vision and direction that would revive the flagging power products business.

Listening to the Users, and Incorporating Their Ideas

"Create a million-selling engine": this was the new target for the Power Products development staff. That figure was consistent with the Three-Pillar Initiative announced by Kiyoshi Kawashima following his appointment as company president in 1973. The initiative reflected Honda's decision to direct its entire corporate effort toward three areas of activity: an expanded motorcycle business, entry into the auto business, and a boost in performance for Power Products. The target, though, also raised concern among the staff with regard to the future of Honda's Power Products operation.

"One million units?" they wondered. The development staff could not believe their ears when they first heard it. That astonishment was understandable, since the total production volume at Power Products was at that point merely 200,000 units a year. They had to bring the number up, not just to 300,000 or 500,000 units but to 1 million, And they had to do it quickly. Everyone was surprised by the request, thinking the achievement of such a target would be impossible. However, one person among them thought it was not at all impossible. He was Hiroyuki Hatakeyama, the man appointed acting leader for the new engine project.

"It's true that we're selling only 200,000 units each year," Hatakeyama said, "but that number is the total of all types and models of complete machines. The goal will look much more attainable if we attempt it with a single-unit engine. First, we must identify the markets that can absorb a million units, then find ideas that are appropriate to the task. After all, we've been putting too much emphasis on engineering [the functions of complete machines]. Therefore, it wouldn't be such a bad idea to focus on the engine instead."

Hatakeyama, though, could sense an impending crisis. One reason was the difficulty of running such a business while focusing on complete machines. With such an emphasis the company would be unable to respond to market needs [using the existing models], because priority had to be given to new-model development. However, quality products would always sell, he thought, and quality products are ones that satisfy the customers who buy them. Technology and ideas are just the tools by which we create quality products.

According to Hatakeyama, the most important point in developing the new engine was to "accurately understand market needs for general purpose engines, then define the requirements for the new product." Doing so, he believed, would ultimately open doors for Honda's Power Products operation. The key to success lay in the determination to listen to the end users' honest opinions, and thus reflect them in the product offerings.

The development project members were assembled from various fields outside the realm of power products. Those involved in motorcycle and automobile development, not to mention experts from Honda Engineering (EG), were included as part of the group. Under the able supervision of Kimio Shinmura, the managing director of Honda R&D and manager of the development project, a team of unprecedented scope and skill was organized, drawing upon the vast expertise from throughout the Honda organization.

The ME project was officially launched, named after its target of a million units, marking Honda's acceptance of the challenge to create an engine representing the next generation in general-purpose products.

An Engine to Beat the Industry's Goliath

The search for engine development concepts had already begun in 1972, well before the establishment of the target million units. However, at that time the world market for general purpose engines was around 10 million units. Of this, around 8 million were accounted for by Briggs & Stratton, a respected U.S. company. That organization was able to maintain highly competitive pricing through mass production, selling engines for less than $100. To find ways to beat the Briggs products, Honda's development staff conducted field studies and interviewed users. Moreover, they studied the difference between Briggs engines and past products developed by Honda. The challenge, though, was to find the trump card that could beat an industry giant. However, the ultimate conclusion was a rather solemn one: Honda could never win in the same arena.

Briggs' engines were popular among home users. They were relatively less durable, but they were low-priced. Honda engines, on the other hand, offered much greater durability since they were based on motorcycle engines. It was said that with Honda engines the core parts such as cylinders and pistons could last more than ten years without failing. There was a world of difference between the Briggs approach to engines and that of Honda, just as there was a fundamental difference between a cotton undershirt and a silk hat.

The "quality products" Honda sought were, of course, more expensive. They were also more difficult to sell in the general purpose market. When asked to choose between a three-year engine costing 10,000 yen and a ten-year engine costing 30,000 yen, the consumer will choose the less-expensive one. Users of general purpose engines simply have different perceptions of value than users of motorcycles or cars.

Let it not be said that Briggs & Stratton engines were not good products, though. They were very good indeed, with a simple style of construction that was perfectly matched to market requirements. Honda, even with its own technologies in place, could not have made the same engines. However, again, Honda had no wish to replicate the engines of Briggs & Stratton.

In order to obtain the winner's edge, Honda had to offer a feature that would dramatically enhance the performance of its engine. Therefore, in September 1973, Honda examined the possibility of applying its CVCC technology to the general purpose engine. Changes in social awareness had already made "ecology" a key element in product development. Since Honda had already adopted the CVCC technology to its automobile models, the general purpose engine was an appropriate candidate for testing. With that the concept of an environmentally-friendly general purpose engine became a feature that would set Honda apart from Briggs and its imitators. It would not be easy adapting the CVCC technology, though, due to the prevalence of the SV (side valve) configuration. Moreover, studies had been conducted with both SV and OHV engines, without achieving the anticipated results. On the contrary, negative aspects had been identified, including a significant decrease in output. Ultimately, the CVCC technology was not used.

Identifying Problems Using Key Criteria

The new engine concept was ready to assume a more concrete form by the spring of 1974. However, thanks to the study of Briggs & Stratton engines, attempts to apply CVCC technology and extensive market research, the development team was beginning to perceive a direction. In the ME project, Hatakeyama had led the effort to define specific product requirements. Unlike previous development projects, in which engineering functions took priority, the ME project intended to identify the product requirements in an engine for which there would be market demand, and subsequently employ Honda technology to those requirements. To do that, Hatakeyama knew it was essential that any existing problems be examined against the same criteria.

The same criteria, according to Hatakeyama, meant "the satisfaction of every customer who purchases the product." After all, general purpose engines were being used in many different ways, so there might be more elements that could not simply be examined on paper. However, Hatakeyama believed that having the greatest possible amount of data on actual engine use would allow Honda to employ that technological capability more effectively. If they could do that, the results would follow suit.

Hatakeyama himself traveled extensively in order that more information could be gathered. He also visited many OEM companies. Combining his experience developing general purpose engines, with his eye as a development engineer, and his five senses, Hatakeyama took as his personal quest the attainment of a million-selling engine. Though he had yet to find it, Hatakeyama was beginning to feel confident that the impossible could indeed be achieved.

A longtail boat with ME engine instead of outboard marine engine in Thailand. The development staff traveled the world defining product requirements.

Summer came at last, and the development team decided to camp in the mountains for a month in order to devise a list of target requirements based on their research. There in camp the nights were long and filled with heated discussions:

"Costwise, we can't compete with Briggs."

"What's the highest we can go and still maintain our price-competitiveness?"

"Are there any selling features that can compensate for the price?"

"What kinds of engines do the OEM companies want?"

"Can we solve the problems regarding mass production?"

"How about making it a two-cycle design?"

"What about sales strategies?"

"It should be an engine that's unique to Honda."

The Research Center staff, along with personnel from EG and sales, joined the discussions, analyzing various points from every possible angle. Finally, the target requirements were defined. For the sake of strategy, it was decided that the engine would target the industrial market. That target was specifically defined as the one in which Honda could make use of a key characteristic in its engines [durability] thereby avoiding direct price competition with Briggs in the home-user market. The development concept, too, was decided: "Tough, durable and costing only half." These words could not fully express the exact desires of each individual involved, but the important thing was that all had come to share a goal through the process of identifying and openly discussing problems. At last they had a banner with which to carry the project.

Defining Toughness and Durability

"Mr. Hatakeyama, how long must the engine last in order to qualify it as 'tough and durable'?" This was a question asked by several staff members after the design process had begun. They said they couldn't actually design the product without specific references. Hatakeyama, though, was often asked similar questions, so his answer was the same as always: "You shouldn't be asking me such questions. How can I answer something like that?"

The target concept of "toughness and durability" could not be quantified as a specific number, since such terms and their interpretations vary according to how the product is used. For example, the same shoes will have different degrees of wear and soiling, depending on whether the person wearing the shoes usually walks, drives or rides a train. In other words, a product is tough and durable if the person who uses it feels it is. For this reason the customer's perceptions serve as the standard of reference. Therefore, it became their objective to make the customer feel that way about the new Honda engine.

Each time a problem was raised, Hatakeyama would gather his staff for a serious brainstorming session. Discussions were held regarding how the engine would be used in the market and how the customer would feel about it. A comment was once raised concerning the problem of seizing, which was of course the biggest headache imaginable. No matter how tough the construction was, the engine would not work if a seizure occurred. Now, the team knew the user might often neglect routine checking, even though it was clearly important. This was as true with power products as it was for cars. Moreover, with an industrial product like a general purpose engine the user would often be different from the person servicing it. Therefore, to make the engine tough and durable it was important to ensure that seizure could not occur even if the engine were to run out of oil. Based on such reasoning, the staff thought of making the engine stop before a seize-up could occur. That idea led to an oil-alert mechanism that automatically stops the engine when the engine oil runs out. Of course, such a mechanism had to do more than simply stop the engine. A winch engine would be useless, after all, if it were to stop while the line was being reeled in or out. Therefore, a repeated trial-and-error was employed to find the ideal point at which the engine could be stopped.

This is a good example of how the staff tackled product development. Rather than emphasizing engineering-oriented ideas, they truthfully satisfied product requirements that reflected real world market needs. This was a complete reversal of Honda's prior approach to development, leading to key innovations such as the point-less ignition system.

The Challenge: Cutting the Cost in Half

The other target (reducing the cost by half) was going to be a difficult one. However, while Hatakeyama labored in his search for a clue, Tadashi Kume, the senior managing director of Honda R&D, gave him a bit of advice: "Why don't you assign a person to be in charge of each function?"

Hatakeyama described the system this way: "For example, if there were twenty functions, we would divide them into groups, each containing an equal number of functions, then assign a person to each function group, such as the tank, carburetor, crank, dynamo, plug, and bearing. Then, based on current cost levels, we would tell them how much they have. For example, if a tank usually costs 800 yen, we assign a person to the tank and tell him, 'You are in charge of the tank. You have a budget of 400 yen.'"

It was a rather forceful approach, but not out of line considering their rather daunting target. They knew they had to transcend the limits of common sense in order to achieve it. Yet, even Hatakeyama thought the costs could never be halved for many of those items. For example, cost-reduction measures for the plug would be limited to minimizing the purchase cost by standardizing the specifications or adopting the most popular size. Still, such measures could only save 3 or 4 percent, and the person in charge of plugs hit a wall. He couldn't cut the cost, because there was simply no room left.

"In such cases, he could get a credit from another group," said Hatakeyama. "After all, there were many groups, so he simply had to find one that was doing well and ask for help."

Halving the cost was difficult for some groups and relatively easy for others. With a reasonable effort some groups could even reduce the cost to less than half. The group that was unable to halve the cost was allowed to get a credit from such a group. Of course, these credits weren't free for the asking. The process was that the struggling group would provide ideas for the collaborating group in order to help them halve their cost. The requesting group would then get the portion saved beyond the 50-percent mark as credit of its own. Through this collaborative process all of the team members were able to pool their efforts on behalf of the same goal. Finally, the team was able to pull off an amazing feat, cutting the overall cost by approximately half.

The cost-cutting struggle, though, meant having to give up some durability. However, Honda engines were already respected for their durability. Since motorcycle engines had long been the basis of such design work, and because the development team was too ambitious in trying to create the best, they would often create products having durability far in excess of what the market expected. Such overzealous efforts were reflected in the cost, making the products technologically superior, but too expensive. Therefore, to achieve its cost-cutting objective the team had to change its mindset and explore ways to squeeze costs while satisfying the requirement for "toughness and durability." Many ideas were attempted in order to achieve it, including a bold plan to change the needle bearings to the plain type. Even pressed flywheels were made through plastics processing and were tested, but never used. Another significant contribution to the effort was the participation of EG personnel in development. This facilitated a collaborative effort between the production engineering side and the design side.

The ME Engine: Combining Honda's Expertise

The ME engine was released in June 1977, finally achieving the sales target of a million units annually, five years later, in 1982. This success, which almost everyone had originally thought impossible, was ultimately realized through a strategy of shifting the development focus from engineering to market-driven requirements and establishing a reachable goal. Moreover, it paved the way for Honda's original general purpose engines, which were no longer limited by the context of motorcycle engines. In this sense, the ME engine fulfilled the purpose of helping achieve the goal stated in Honda's Three-Pillar Initiative.

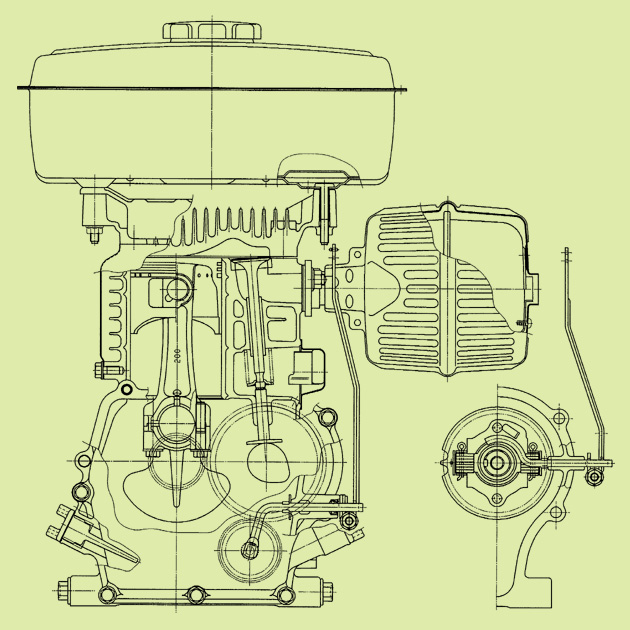

A structural diagram of the G200, the first in a series of engines derived from the ME unit

Personnel from Sales and EG were instrumental in the drive to succeed. Particularly, the joint development effort with EG personnel made it possible to put the project in clearer perspective. The ability to discuss issues of mass production and cost reduction helped the team achieve an optimal product balance for the ME engine concept. That kind of thinking eventually grew into the S/E/D system.

The ME engine therefore represented the combined expertise of the Honda organization. It would not be unreasonable to say the engine opened the door to "tomorrow" on behalf of Honda Power Products. By defining a new approach to development focusing on product requirements, the ME engine became the context for leadership in the field of power products.

Hatakeyama discussed the reasons behind the success of his team in ME engine development: "The ME engine would never have materialized if the target had been any less than 1 million units. With that target, we were able to identify various ideals and adopt a new approach. Certainly, it was an outrageous number, and ideas were the only resource we had available to us. Of course, we had a great deal of difficulty reaching this seemingly impossible goal, but we didn't think of the target as a number, but the one million customers we would satisfy. We believed that was necessary in order to reach the goal."