Completion of Suzuka Circuit / 1962

"I Want a Venue for Motor Racing!"

"I want to have a venue for motor racing. Automobiles cannot be improved if they are not put through their paces on the racing circuit."

This prescient statement by company founder and president Soichiro Honda, made around the end of 1959 during a meeting to propose the construction of a welfare facility for the Suzuka Factory, led to the birth of Japan's first full-scale road racing circuit.

In those days, the Asama Volcano Race was still held in the Asama Heights area. However, the course on which the race took place had been constructed as a test course for motorcycle manufacturers who did not have their own proving grounds. In fact, the purpose of the course's construction was to enable these manufacturers to "fulfill their responsibilities in the sale of quality products." But since the automobile manufacturers had not agreed to the construction of a fully paved course, as was originally planned, it was not possible to secure funding sufficient for the purchase of paving. As a result, car races had to be held on a dirt course.

However, as better motorcycles were developed with speed and performance exceeding the levels for which the course was originally intended, safety became a major concern for competitors and spectators alike. Ultimately, the Asama Volcano Race was discontinued following the 1959 event. On the other hand, motorcycling was steadily becoming more popular with urban thrill seekers, who took to the streets in a quest for excitement. These rowdy riders led to the emergence of so-called "Kaminari Zoku (groups of thunderous riders)," which soon became a social problem. The industry feared the trend could damage the motorcycles image as a safe and pleasurable means of transportation.

Soichiro Honda had a basic philosophy: Unlike dry goods dealers and furniture builders, motorcycle manufacturers are entrusted with an irreplaceable commodity called human life. Being true to this ideal, the company had worked hard to fortify its conviction that it was a hallowed obligation as a motorcycle manufacturer to build a race course with which they could develop the types of high speed machines demanded by increasingly speed-conscious consumers that were safer and more predictable. Honda had successfully completed its debut in the Tourist Trophy (TT) Race on the Isle of Man in 1959, and was badly in need of a venue for high-speed running tests to develop production models.

"Do Not Destroy the Rice Fields!"

Soichiro Honda ordered the formation of a project team, which was quickly formed by Takeo Fujisawa, the company's senior managing director. Honda Motor began an independent effort to build a full-scale, European-style, fully paved course, which was to be the first of its kind in Japan. Also represented in Fujisawa's plan was a recreational facility that could become the basis for promoting and harnessing the enthusiasm for motor sports among teenagers, since they were to become the motorcycle riders of the future. The facility was also intended to become a center for research and education concerning motor science and technology.

Because Japan had no existing course to use as a model for the Honda project, the team's initial task was to collect information on the famed racing circuits of Europe. Based on data from several key facilities, the project team concluded that land area of 660,000 to 990,000 square meters was needed to accommodate a circuit of 6 km in distance per lap. The team then began the process of site selection. Several potential locations were selected throughout the country, and personnel were sent to each of them to conduct detailed studies. Among these sites, the city of Suzuka, with its attractive geographical characteristics, stood out. In addition, the municipal government showed strong support for the project. For example, they assigned the same officials who had assisted Honda personnel when they came to see the potential construction site for Honda's Suzuka Factory. They also provided aerial photographs of the site. In spring 1960 a decision was made to select Suzuka as the site for construction of the race course.

However, the project team encountered unexpected difficulties concerning land acquisition and the permits they would need to obtain from the authorities. The public had come to misinterpret the company's intention of building stands for spectators as one in which "Honda was actually planning to build a race course for gambling."

Meetings were held at Suzuka Town Hall night after night, during which the Honda representatives and Suzuka's deputy mayor attempted to persuade the landowners and local residents. And thanks to a rather casual atmosphere and the help of a little sake (Japanese rice wine), the people were soon moved to accept Honda's view of the project.

The original plan called for a course to be built amid an area of rice fields. However, after Mr. Honda ordered that the precious fields not be destroyed, it was decided that a relatively wild section of mountainous land nearby could be used instead.

Resolving Technical Problems with New Construction Methods

The layout for the course was originally completed in August of 1960, but due to rising construction expenses and other setbacks the brilliant design - which featured two hairpin turns and three multilevel crossings - had to be revised. Thus, in December of the same year the project team traveled to Europe to visit local circuits and study their facilities, racing rules and systems of operation in order that an agreeable solution might be reached. Team members peeled off surface materials from the circuits, even Germany's famed Autobahn, using shoe lifters, then brought those materials home with them. More than mere souvenirs, these fragments of racing history became priceless technical information, ultimately facilitating a technical solution to the problem of asphalt paving, which had indeed been a major obstacle.

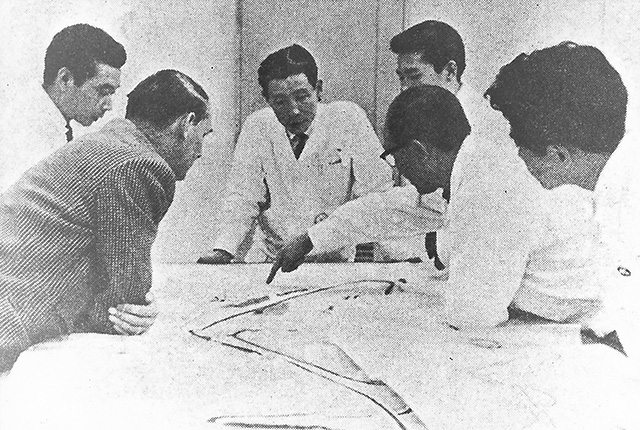

Soichiro Honda (second from right) discussing a design model for the Suzuka Circuit with members of the project team

Nippon Hodo, a company contracted to pave the course, had no experience in surface paving for road racing courses, although it had some experience working with oval test courses. While analyzing the surface material the team members brought back from Europe, the company's engineers studied river sand taken from various locations. It took them approximately six months to collect and analyze their data, at which they decided to use a type of rock found along the Kiso River.

The construction work was not without problems, either. Since the drawings left ample room for

adjustments, there were numerous occasions upon which the specifications had to be altered and drawings created after the fact, simply to reflect the specifications. In addition, new construction methods were used for sections of the multilevel crossings to overcome difficulties arising from a rigorous requirement for flatness and consistency.

A view of the construction site, near the grandstands (photo courtesy of Sadao Shinozaki)

The construction project attracted much attention, and the staff involved in the Meishin Expressway, a section of which was just being started in the Yamashina district of the Kyoto Prefecture, traveled as far as Suzuka to observe the work.

When the construction was nearly complete, Soichiro flew over Suzuka Circuit by airplane and said, "They are doing a good job of creating a course that is close to what the drawing envisions." The efforts of the construction staff were duly rewarded by such a comment.

A ceremony commemorating the completion of the Suzuka Circuit was held on September 20, 1962.

Organizing the All-first Races

In November, two months after the completion ceremony, Suzuka Circuit hosted its first race: the first Japan National Road Racing Championships.

Motorcycle racing on a full-scale road circuit was the first race in all respects for organizers and amateur riders in Japan alike. Even among the professional riders, only a handful had participated in that type of racing overseas. In order to establish appropriate rules - the very first task for the organizers - the rule book for the Isle of Man TT Race was sent from England and modified through discussions with other manufacturers. The riders divided themselves into groups, each according to the make of his machine, and took lodging at ryokans (Japanese hotels) in Suzuka before the race for driving training.

The organizers had expected approximately 100,000 visitors for each of the event's two days, based on receipts from advance ticket sales. However, they had no idea what would happen with the gathering of such an enormous crowd.

The first day opened amid a downpour of rain. The visitors had to struggle to make it from the parking lot to their seats in the stands. Women dressed in beautiful clothes soon became drenched head-to-toe in mud. One account claims that raincoats, socks, and underwear were completely sold out at the shops in nearby Shirako. The race even had to be stopped on one occasion because several spectators had tried to make a shortcut to the stands by climbing the security fence and crossing the course.

The race, however, went relatively smoothly, The large crowd of people, for whom road racing was an entirely new experience, was stunned by the speed, the roar of the engines, and the smell of oil from the machines flying by in front of them. Surely they were witnessing firsthand the dawn of serious motor sports in Japan!

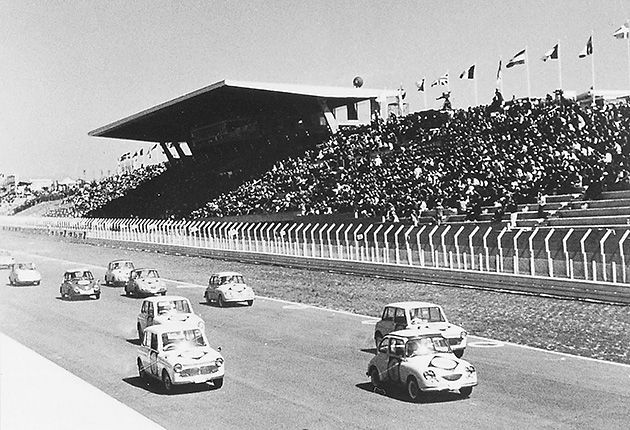

Spectators watching the senior 50 cc race of the first Japan National Road Racing Championship

In May of the following year, the Suzuka Circuit hosted the first Japan Grand Prix Auto Race. It was the very first such race for automobile manufacturers as well as drivers. Equipped with column-mounted gear shifters and conventional tires with white sidewalls, the machines were far behind their foreign counterparts in technology. There were also a few heated disruptions among the drivers.

First Japan Grand Prix Auto Race (photo courtesy of Sadao Shiozaki)

However, the completion of Suzuka Circuit and the two major races held on the course represented a significant contribution to improvements in high-speed durability, which with the construction of a series of expressways - namely the first, the Meishin Expressway, which opened partially in 1963 between Ritto and Amagasaki - became a requirement for motorcycles and cars alike. Moreover, the technical levels of not only automobile manufacturers but parts suppliers, as well, were dramatically enhanced because of the Suzuka Circuit and its earliest racing events.

Enhancing the Popularity of Motor Sports

January, 1963 saw completion of the first phase of construction for a theme park designed to expand the audience of motor sports enthusiasts. Fujisawa had conducted a study on Disneyland, in the United States, prior to building the park. When he saw how sparkling clear the park was - not a single piece of litter on the ground - and that the attractions were full of ideas from the creative genius of Walt Disney, he was struck with the potential of a park operation that was designed to please the visitor. So it was that Fujisawa vowed to make the Honda park an oasis for tourists and visitors alike, and that it would remain Free of litter.

The automobile theme park soon after its opening

Fujisawa also spoke the philosophy behind launching the Honda Land park, addressing young Honda Land employees at the park's 25th anniversary celebration, held in 1986. "At Disneyland," he said, "they create products and provide them to visitors in complete form. At Honda Land, though, we've created a system in which each and every visitor can create his or her own fun. From the beginning, Honda Land has operated according to unique philosophy, which makes it 'different' from others. It's an experience that is not found at Disneyland or any other place."

Featured at the park were motorized rides using Honda engines that users could control to travel on land, in water and in the air. The park immediately captured the hearts of many school children with its unique concept and fun rides. In 1966 Honda established Tech Production in order to begin the in-house development and manufacturing of unique, innovative rides focussing on safety.

Kyoto, Nara and the lse/Shima region were among the more popular destinations for school trips in those days. A typical itinerary might include a visit to the famous petrochemical complex in Yokkaichi City, along with the Suzuka Factory. Students could participate in an automotive class, enjoy the theme park and stay overnight at the Suzuka Circuit. Thus, Suzuka Circuit became a new destination for school trips, where students could experience many things as they were "seeing, hearing and doing." Indeed, students from elementary and junior high schools throughout the country soon became attracted to the experience. In 1966 alone more than a million people visited the park, and a 500-person-capacity hotel designed exclusively to accommodate school students opened the following year.

In view of increased commuter traffic following the opening of the Meishin Expressway, Suzuka Circuit began offering driving lessons to the police force in September of 1964, in response to a request by local bureaus for training in the safe maneuvering of motorcycles and cars. Recognizing the need to improve driver skills and maintain them on a par with steadily improving vehicle performance, the Suzuka Circuit organized the Safety Driving Study Group, which was comprised of representatives from government agencies and private companies. This move led to the establishment of the Traffic Education Center.

Traffic Education Center

Becoming a Suzuka for the World

The Suzuka Circuit is now home to some of the world's most popular championship series events, including the Formula 1 Grand Prix, the World Motorcycle Grand Prix, and the Eight-hour Endurance Race. However, behind the glamour and excitement of these magnificent sporting events are the years of work and painstaking efforts of the many organizers involved in bringing them to Suzuka.

It was 1978 when the ever-popular motorcycle endurance race was resumed after a brief hiatus following the OPEC Oil Crisis. The hours were reduced to 8 from the original 10, and the Eight Hour Endurance Race - affectionately known as the "Gendai Oise Mairi (modern pilgrimage to the Ise Shrine)" - was born. in order to bring excitement to riders and spectators alike, an elaborate scenario was written in which the machines would pass the finish line with headlights brightly lit against the backdrop of the most romantic sunset. The timing for the start and finish were set according to that scenario.

FIM World Championships "Coca-Cola" Suzuka 8-hour Endurance Race (1990)

Race organizers, however, faced many problems in bringing the Formula 1 Grand Prix to Suzuka. Among them were modifications to the course and pit areas, advertising rights to billboards alongside the course, accommodations, and the transport of machines. For example, the radio systems used during the race were found to be in violation of Japan's Radio Control Act. Bread makers had to be brought in from France, and Italian restaurants had to be built to satisfy the drivers, engineers and officials visiting from overseas. The organizers had to deal with problems ranging from technical issues to rather unexpected ones concerning clothing, food and accommodations. But in light of their accountability and perseverance in these efforts, the organizers were awarded the Formula 1 Best Organizer Award - the highest honor a hosting circuit can receive - in 1987 and again in 1989.

The start of Japan's 1987 Fuji TV Formula-1 Grand Prix race

Since its completion in 1962, Suzuka Circuit has walked a rather difficult path, much as the forerunner in any other field would have to take. Certainly it has become an important landmark, and today most Japanese readily acknowledge Suzuka as the place where the Suzuka Circuit is located. In the racing world, Suzuka Circuit has built a solid foundation as a "Suzuka for the world," receiving high remarks among motor sports enthusiasts across the globe.

Nowadays, young Japanese racers who grew up training at Suzuka are competing in the world racing circuits without hesitation expressing themselves in English in their winners' interviews. How could anyone have expected such a thing 30 or more years ago?

Suzuka Circuit has indeed played a vital role in improving Japan's automotive technologies, contributing to the development of motor sports and fostering young drivers talented enough to compete on the world stage.