Second Era of Honda F1 Participation:

Developing Engineers and Technologies Through Extremely

Difficult Challenges

In July 1983, Honda competed in the Formula One World Championship (F1) race with the Spirit Honda 201C powered by a Honda engine. This marked the beginning of the second era of Honda F1 participation. Honda started competing in F2 in 1980, and won the European F2 Championship in 1981, steadily gaining a foothold for a return to F1.

Both Kiyoshi Kawashima and Tadashi Kume competed in the Road Racing World Championship Grand Prix (WGP) and the first era of F1 participation as a team director and engineer, respectively. Kawashima was the main driving force behind Honda’s return to racing, and Kume took over with the lead role with the same passion for motorsports.

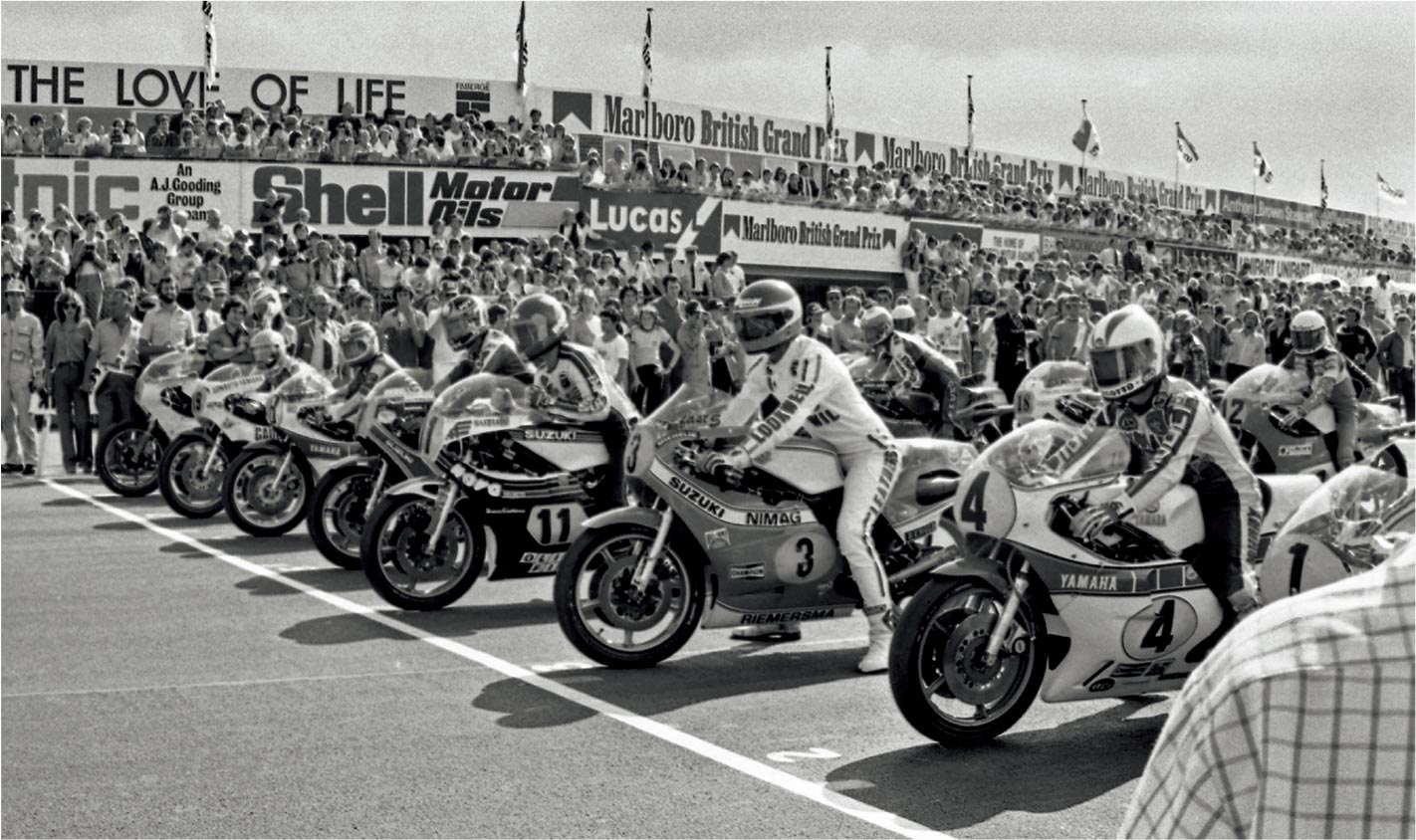

The return of Honda to F1 racing after a 15-year hiatus made headlines around the world. At the British Grand Prix (GP), the first race after the return, the Honda machine retired after only five laps. However, Honda partnered with Williams for the South African GP, the final round of the season, and the Williams-Honda FW09 finished fifth in its debut race.

Spirit-Honda 201C competing in the British GP (July 1983)

The Honda team included the general manager Nobuhiko Kawamoto (who later became the fourth president of Honda) and a group of engineers, mostly young engineers with no previous experience in F1 racing. In July 1984, the team competed in the Dallas GP with the aim of further developing young development engineers through the extremely difficult challenge of racing. While many machines retired due to overheating in the brutal 40C (104F) Texas summer heat, Wiliams-Honda FW10 captured the first race win, overcoming some engine and chassis problems. It was the first victory for Honda in 16 races since its return to F1, but the team members came to realize that they had to overcome a critical issue related to basic engine performance. The Honda F1 engine was lacking sufficient horsepower to win on the European circuits.

Appointing Yoshitoshi Sakurai as a new general manager and adding Katsumi Ichida to the team, Honda tripled the size of the development team over a two-year period. The young engineers assigned to the engine design made an unexpected move. Instead of following Kawamoto’s instructions, they took their own unique approach to the engine development.

Kawamoto later recalled, “(The engine they built) was completely different from what I had instructed them to build. Following the way of thinking the Old Man (Mr. Soichiro Honda) taught me, I had instructed them not to deviate from the original direction without thoroughly ascertaining if it would work. But they totally ignored my advice and came up with something different. And, it worked beautifully.”

This was how the RA165E engine was created featuring the new design with a smaller bore and longer stroke. The Williams-Honda team began using this new engine from the Canadian GP, the fifth round of the season, in June 1985, and won four races during that season.

Gradual generational change took place within the Honda F1 team, in the areas of both engine design and team management. In 1986, with the rise of the younger generation of Honda engineers, the team finally won the Constructors’ Championship title, an honor for everyone who was ever involved in the challenges Honda took on in F1.

The new-generation members of Honda F1 team began to think, “If we are going to take on this challenge, we want to achieve an overwhelming victory.” To this end, Honda decided to pursue its racing project with a completely scientific approach. In fact, Honda became the first company that applied computer-powered analysis and control in F1 racing. To be more specific, Honda developed a telemetry system to identify the cause of machine problems and breakdowns and introduced a system to determine an event or situation affecting the machine based on data, rather than relying solely on engineers’ previous experience and intuition. Confirming the validity of this approach, Honda won nine races in the 1986 season, followed by 11 wins in 1987, and an incredible 15 wins out of 16 races in 1988. Moreover, in 1989, the first season after new engine regulations went into effect requiring the transition from turbo to naturally aspirated (NA) engines, Honda won 11 races, ushering in a new era of Honda domination in F1.

Competing in WGP with Honda Pride as

a Motorcycle Manufacturer

In parallel with the return to F2 and F1, Honda returned to the WGP in 1979, twelve years after its withdrawal at the end of the 1967 season.

At the time, the majority of Honda R&D development engineers were assigned to the automobile development division, and the motorcycle development division only had a third as many members as it had at the beginning of 1960.

Following the introduction of the CB750 Four in 1969, Honda continued to launch a series of popular models during the 1970s. However, even after the establishment of a dedicated motorcycle R&D center in Asaka in 1973, the backbone of Honda motorcycle technologies remained the same as it had been in the 1960s, when Honda withdrew from the WGP. If this situation would continue, world-leading Honda motorcycle technology would be left behind in the times. With such a sense of urgency, Honda decided to return to WGP with the aim of raising a new generation of world-class engineers and developing new revolutionary motorcycle technologies. Honda launched the New Racing (NR) project and allocated an annual budget of around 3 billion yen and 100 associates for the development of new racing machines.

At the time, the mainstream of WGP machines featured a 2-stroke engine. However, having achieved all its previous WGP success with 4-stroke engines, Honda was determined to make a comeback to WGP with a new 4-stroke engine. This would not be a refined version of previously developed engines, but require the development of new revolutionary technologies.

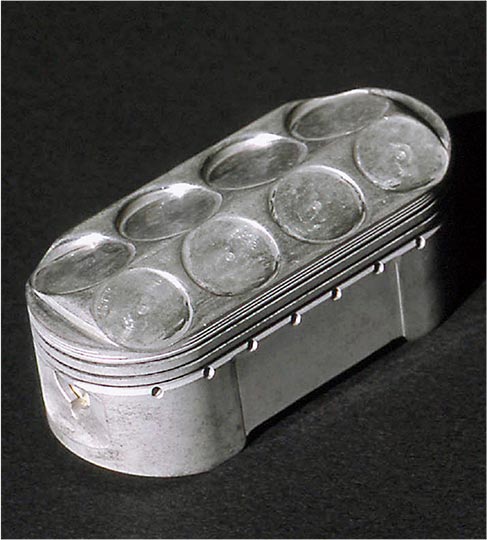

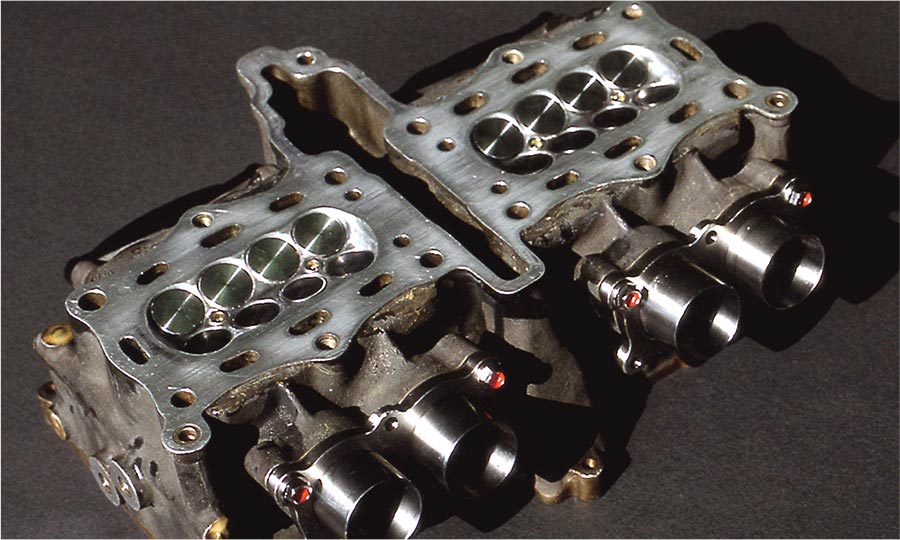

In pursuit of greater power, Honda engineers came up with an idea to adopt an oval piston design which could take more valves than a conventional round piston. The oval piston could incorporate eight valves per cylinder, thus enabling construction of an engine equivalent to a V8 32-valve engine with four cylinders, which was the maximum number of cylinders set forth by the WGP regulation at the time. The oval piston engine required an extremely high level of production technology and machining precision; thus, it was unprecedented to equip racing machines with an oval piston engine. However, at Honda, both management and engineers believed that if there was even the slightest chance of success, it would be worth taking on the challenge.

Oval piston

Cylinder head

Within the NR project team, a group to focus on the engine materials was formed to study optimal machining precision and durability, and to explore new materials such as advanced composite materials. Through trial and error, the group successfully developed and manufactured engine parts that could withstand the engine’s high rotational speed. The new Honda WGP machine, NR500, made its debut in August 1979 at the British GP, where it qualified for the event but didn’t complete the final race. The NR500 was packed with a number of newly adopted technologies, including a monocoque frame, nicknamed “shrimp shell,” made of 1mm-thick aluminum sheet, as well as 16-inch wheels. So, it was inevitable that the team could not address all of the machine troubles that frequently arose in the heat of actual races. It was not an easy task to perform maintenance and realize the best settings for the race in the limited time available for the qualifying.

In August 12, 1979, the NR500 made its WGP debut at the British GP (Silverstone Circuit), however, it struggled from the start of the race with push starting of the engine.

The NR500 was repeatedly tested and perfected at Suzuka Circuit. The rider in the photo is Mick Grant.

The NR500 was repeatedly tested and perfected at Suzuka Circuit. The rider in the photo is Mick Grant.

In March 1983, Freddie Spencer won his first 500cc World Championship at the South African GP with a dominating performance. At the final round of the season, Spencer clinched the World Championship title for the season and Honda won the Constructors’ Championship title for the season.

In March 1983, Freddie Spencer won his first 500cc World Championship at the South African GP with a dominating performance. At the final round of the season, Spencer clinched the World Championship title for the season and Honda won the Constructors’ Championship title for the season.

Based on the lesson learned in the first year, the NR project team worked on the design of a highly competitive chassis for the NR500. The bike was then raced in the All-Japan Road Race Championship and perfected as a winning machine. In June 1981, at the Suzuka 200km race, the sixth round of the All-Japan Road Race Championship, the NR500 finally captured its first win. Furthermore, in July of the same year, the NR500 finished first in a five-lap heat race held at Laguna Seca in California, which was also the qualifying round for an international race.

All that remained for the NR500 was to win a WGP race. While the NR500 was struggling to achieve that goal, Honda began the development of new machine, NS500, equipped with a 2-stroke engine, and decided to debut the machine in the WGP. At the Argentine GP, the first round of the 1982 season, the NS500 finished third; the first podium finish since Honda returned to WGP. Then, at the Belgian GP, seventh round, NS500 brought Honda its long-awaited first WGP victory. Based on these results, the NR Project team made a decision to shift its development efforts to the NS machines, and the NR500 ended its role in the WGP.

Over its four years of WGP racing, the NR500 could not win any GP point, however; the development process of the NR500 contributed to the growth of many Honda engineers, and resulted in a number of technologies and know-how later applied to various production models Honda introduced to the market. Through the challenge it took on in WGP, Honda gained a new-generation of ultra-high-rpm, high-output 4-stroke engine technologies. Moreover, this challenge also resulted in advanced technologies, such as aluminum twin-spar frames and magnesium wheels, which became a driving force behind a major breakthrough in motorcycle technology Honda achieved in the 1980s.

In 1983, Honda captured the WGP Championship title with the NS500 and the Constructors’ Championship title in the 500cc class for the first time in 16 years.

Technologies and Global Presence Honda Gained

by Taking on Challenges in Racing

Honda has a history of gaining technological advantages for its production models through its participation in F1 and WGP, the world’s most prestigious automobile and motorcycle road races.

The fact that Kawashima and Kume, who both competed at the forefront of racing, served as the president of the company consecutively was one of the major factors working favorably for Honda to earn prominence in the world of motorsports. In fact, starting from the mid-1980s, shortly after Honda returned to F1 racing, a number of sporty models, namely the Ballade Sports CR-X, Civic and Quint Integra were added to the lineup, which further solidified the image of Honda as a sporty brand.

In the meantime, F1 racing had been the major event that represented motorsports culture in Europe. Therefore, the success in F1 had a tremendous impact on automakers’ sales revenue in the European market. During the second era of F1 participation, Honda partnered with Williams, Lotus and McLaren, which were all British teams. The timing when Honda began technological collaboration and joint development with British Leyland (BL), a British automaker, also coincided with the time when Honda was making a significant leap in racing. Then, in 1985, Honda established a local subsidiary, Honda of the UK Manufacturing Ltd. (HUM), and began local production in the U.K.

Whenever Honda participated in F1, there was always a cause unique to Honda. Such cause of the first era of F1 participation was “to gain entry into the automobile market,” and for the second era, it was “to win the competition against major European automakers.” The success formula for the global business expansion that Honda learned by taking on difficult challenges in racing in its founding phase was inherited by the next-generation Honda leaders in the growth phrase, and they pursued racing with the aim to embody the “glocalized” Honda in Europe.

Building a Participatory-Style Racing Circuit

in the Pursuit of Dreams of Future Mobility

On August 1, 1997, Twin Ring Motegi opened, featuring a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) oval course and a 4.8-km road course, as well as various driving courses and a traffic safety driving training center.

In the mid-1980s, after the storm of fierce competition in the motorcycle market caused by the HY War had subsided, the motorcycle sales division at Honda Motor came up with a plan to increase the number of motorcycle fans and enthusiasts by building a “Motor Gelände” – a race track where more people can participate in and enjoy the fun of motorsports activities. In February 1986, the Motor Track (MT) Project was launched with a team consisting of members from the motorcycle sales division and the division responsible for promoting recreational activities involving motor vehicles. Honda had built the Suzuka Circuit as a facility for more people to enjoy watching motorsports activities, but now the company wanted to build a facility for more people to participate in and enjoy various activities with motor vehicles. Honda recognized that building a world-class facility where customers can use and enjoy motorcycles, automobiles and various power products would be a role that Honda must assume as a manufacturer of such mobility products.

The prime candidate site for such a facility was located in the mountainous area in Motegi-machi in the Haga District of Tochigi Prefecture. The site was as large as 640 hectares, three times larger than the site of Suzuka Circuit, and it was only about 100km away from Tokyo as the crow flies, or about two hours by car. In 1988, Honda announced its plan to build the “Mobility World Motegi (tentative name),” a large facility centered on Japan’s second international circuit, after Suzuka Circuit.

To pursue dreams and share joys with people and society, rather than going after short-term profit – Adhering to this is principle is the corporate philosophy that has been handed down since the time of the founder, Mr. Soichiro Honda. Kume instructed the project team to work on this project while maintaining a long-term and international perspective, and conveyed his desire to build a dream-inspiring facility with ample scale.

In the back of his mind, Kume already had a vision of the sort of future Honda should be striving for.

In later years, Kume explained the foresight he had at the time:

“By then, Japanese manufacturers had built their production operations all around the world, and I had a vision for the future of Japan, in other words, how Japanese industries would generate profit in the future. Exporting was already becoming difficult [...] So, I knew that ultimately Japan would have to leverage its intellectual properties because Japan had no natural resources. So, what about the automobile industry? What would be the intellectual properties of automobiles? Building automobile R&D centers would not be enough. I was thinking that we needed a place where automobile users can familiarize themselves with and have fun with automobiles, more as a part of their cultures. I thought we could create something good as part of the regional culture if we could build such a facility in the Kanto region. I thought it would be nice to build the epicenter of automobile culture or something like that. That was a dream I had, and I was not sure if we could or could not realize such a dream. But if we could build such a place, I knew that people who like cars and other motor vehicles would come together and start various things.”

Kume was envisioning to build a place and culture where more people could touch, create, enjoy and play with mobility products. What encouraged Honda to invest resources in the pursuit of its dreams of future mobility was Kume’s desire to see Honda continue being a company that brings joy to society.

In 1997, nine years after the plan was announced, Twin Ring Motegi (later known as Mobility Resort Motegi) finally opened. In addition to a road course, the facility also featured an oval track built in anticipation of hosting IndyCar Series races in Japan. In fact, Twin Ring Motegi successfully hosted its first IndyCar Series race (Indy Japan 300) in 1998.

Honda launched the MT Project at a time when Honda was making remarkable progress in the second era of its F1 participation, and generating an F1 boom in Japan. Also, in the U.S. the locally-produced Accord had become a big hit and the Acura brand was taking off. By around this time, Honda had activated its strategy for taking part in the world of racing in the U.S.

Through its racing subsidiary, Honda Performance Development (HPD, currently Honda Racing Corporation USA), AHM began participating in the IndyCar Series as an engine supplier in 2003.

Raging Waves of the Times Stand in the Way of

Honda’s Growth

Looking back, during the founding period led by Mr. Soichiro Honda and Mr. Takeo Fujisawa, Suzuka Factory was built with an eye toward the mass production of Super Cub. Honda leveraged this capital investment to enter into automobile business, and the construction of Suzuka Circuit and first participation in F1, which occurred around the same time, provided a tailwind for a series of breakthroughs Honda made in its automobile business.

Then, during the growth period led by the second generation of Honda leaders, namely, Kawashima and Kume, despite the difficult economic environment with abrupt depreciation of the dollar/appreciation of the yen triggered by the translation to the floating exchange rate system, Honda leveraged the success of Civic models and successfully established local production operations in Ohio, which solidified Honda business in the U.S. market. The success in the U.S., in turn, paved the way for the global expansion of Honda operations.

However, at the start of the 1990s, the economic situation drastically changed again. The Nikkei stock index began to plummet in February 1990, and the Japanese economy, which had been steadily growing until then, stalled rapidly. The real gross national product (GNP) of Japan fell into negative growth due to the collapse of Japan's “bubble economy” or the collapse of the asset price bubble. In addition to the decline in automobile sales in Japan caused by the sharp drop in consumer spending, Honda-specific issues also became apparent. Honda didn’t have a “one-box” minivan or RV models in its lineup, despite the fact those models were becoming increasingly popular. Honda had lost touch with consumer needs of the time and suffered a critical sales slump due to the lack of cars to sell.

Under the leadership of Kiyoshi Kawashima and Tadashi Kume, Honda continued to make strong progress in global expansion, which the company founders strived for. Honda also developed human resources and advanced technologies by resuming motorsports activities that solidified the foundation of the company during the founding period. Through these initiatives, Kawashima and Kume successfully put the company back on a growth trajectory. However, it was an undeniable fact that the speed that Honda could address various issues had slowed down as the company size grew bigger. Due to the great growth Honda had achieved on a global basis, it faced some difficulties in steering itself toward the right direction in the upcoming era during which the Japanese economy was suffering from a prolonged recession that triggered the burst of the “bubble” economy and also from the great wave of the post-Cold War globalization of the world economy.