Addressing Issues Preventing Local Production

in the U.S.

While Honda was making rapid progress as an automaker leveraging strong sales and the reputation of Civic and the CVCC engine, the U.S. automobile industry was suffering from plummeting sales of large-size models due to the impact of the first oil shock (The 1973 Oil Crisis). U.S. automakers had not fully established environmental technologies necessary to comply with the U.S. Clean Air Act of 1970, nor had they made progress in the development of economy cars the market was demanding at the time.

While Amerian automakers were struggling, smaller cars of European and Japanese automakers were gradually expanding their sales channels. There were concerns that sluggish sales of American automakers would lead to a decline in morale among the production staff as well as product quality.

Kawashima's goal of global expansion had to be in line with the reality of the local economy and society and the automobile industry. With an assumption that the U.S. government would tighten import restrictions, Honda had to take on challenges and pursue local production in the U.S.

In January 1976, the study group exploring the feasibility of local automobile production in the U.S. met with some local members of American Honda Motor (AHM) and held discussions on local production. Surprisingly, AHM members didn’t support the idea of producing automobiles locally in the U.S. because of their experiences being plagued by frequent breakdowns of their American cars. “Rather than going to all that trouble,” they all said, “keep making Civic in Japan and keep sending them to us (while Civic sales are going strong).” Quality control was the main concern. What kind of production management would enable the production of high-quality Japanese cars in the U.S.? Which plant location would provide a production environment where Honda could produce high-quality products? Those two points became the focus of the study group.

In the spring of 1976, Honda began negotiating sales of CVCC engines to Ford. The president of Ford at the time, Lee Iacocca, praised the newly introduced Accord CVCC, “I drive it to work, and it’s a wonderful car,” and expressed his interest in seeking supply of the CVCC engine. At the negotiation meeting, Honda representatives told their counterparts at Ford that Honda was exploring the possibility of starting automobile production in the U.S. and asked if it would be possible to have a tour of Ford’s main factory. In response, Ford arranged a tour of their state-of-the-art factory.

Like many other automobile factories in the U.S., it was a knockdown production plant, which brought in major components from Detroit, Michigan by rail transport and produced small volume of multiple models. Honda representatives who participated in the tour observed that communication between factory manager and production workers was excellent, as was the factory’s overall productivity; however, at the same time, they sensed the limitations of knockdown production system.

In fact, Honda had already established an original production system that did not require large-volume production as a prerequisite. To be more specific, in 1974, two years before this Ford factory tour, Honda established Honda Engineering Co., Ltd., a subsidiary specialized in production technologies and die fabrication. This company had successfully developed various high-efficiency production technologies, including high-efficiency welding machines, and realized the start-to-finish production system that started with a stamping process capable of producing multiple models more flexibly with quick die changes. This tour of a Ford factory gave Honda some general ideas about the means of production Honda should bring to the U.S., including Honda’s original flexible production system, and what models should be produced locally in the U.S.

Following the factory tour, Honda began a location study (survey of potential factory locations) in search of a location where Honda could produce 100,000 vehicles annually and transport the vehicles by train or truck all around the country.

Ohio in the Midwest became one such candidate location based on its economic advantages. In the meantime, some local Honda dealers expressed concern about the decline in quality that local production in the U.S. might cause. To address this concern, Honda commissioned a university research organization to conduct a workforce survey, which confirmed the strong work ethic and high employee retention rate in the candidate area.

Key conditions for the factory location included 100 to 200 acres (400,000 – 800,000 m2) of flat land with good access to highways and railroads, as well as the availability of high-quality labor. The study group members looked into more than 50 potential sites within the State of Ohio; however, the search ran into a deadlock when none of those sites met the requirements. Believing that the only way to find a breakthrough was to talk directly with the Ohio state government, Honda requested a meeting with the Governor of Ohio. At the meeting, the land east of the Transportation Research Center (TRC) near Marysville, managed by the state government, was introduced. The TRC is a large-scale automotive proving ground which includes various testing facilities for cars and trucks. This vast land, with an official U.S. Numbered Highway and rail line nearby, was an excellent location for an automobile production plant. The Governor offered the land free of charge, but Honda proposed purchasing it for a suitable price, which set the stage for Honda to pursue local automobile production in Ohio.

Panoramic view of Honda Marysville Auto Plant (MAP) in Ohio (photo taken in 1989).

MAP consisted of a motorcycle plant (front) which began production in September 1979 and an automobile plant (back), which began production in November 1982.

Taking Root in Ohio with a Thorough Localization Approach

In October 1977, Honda signed an official agreement with the State of Ohio and made a simultaneous announcement in the U.S. and Japan of the plan to build a motorcycle plant to be followed by an automobile plant. The plan was to invest $25 million (approximately 6.5 billion yen at the exchange rate at the time) to build a motorcycle plant on 214 acres (approx. 870,000 m2) of land and produce 60,000 units of large-size motorcycles annually. The new plant would hire 300 to 500 associates and begin production in two years, in 1979. The second part of the plan was to begin automobile production on the site adjacent to the motorcycle plant, once motorcycle production was well underway and requirements such as understanding the local community had been met.

In February 1978, Honda of America Mfg., Inc. (HAM)*3 was established to operate Honda production plants in Ohio. Kawashima’s goal for local production in the U.S. was not merely to build highly efficient and profitable plants, but to have Honda vehicles produced by American people for American people to enjoy them. To this end, Honda decided to reinvest the profits Honda would earn in the U.S. into activities rooted in the U.S. society instead of repatriating it back to Japan. Based on this policy, Honda decided that 80% of HAM's capital would be funded by AHM and the remaining 20% by Honda Motor.

Moreover, to thoroughly implement its policy, Honda only sent 11 associates from Japan to establish and start operation of HAM and made sure they lived in various neighborhoods in Ohio so that they could quickly fit in with the local community. Based on the belief that localization of production operations would be meaningful only if Honda Philosophy takes root in the U.S. as well, HAM committed to hiring locally and returning the profit to the local community.

On September 10, 1979, a line-off ceremony was held for the first CR250R unit produced at HAM. Shown aboard the bike is Kazuo Nakagawa, the first president of HAM.

On September 10, 1979, a line-off ceremony was held for the first CR250R unit produced at HAM. Shown aboard the bike is Kazuo Nakagawa, the first president of HAM.

Furthermore, it was decided that all HAM employees would be called “associates,” meaning members of a team working together to achieve a common goal, instead of “employees” which was a general term used in the U.S. for factory workers. When hiring, HAM placed more importance on motivation to work and passion toward “monozukuri” (the art of making things) of each applicant rather than on their previous work experience. HAM enhanced the work motivation of its associates by adopting an employee benefits system that was unique at the time, including a cafeteria designed for everyone to eat together and first-come, first-served parking lots with no reserved spaces for managers. Moreover, work rules were localized and instilled while taking into account differences in the mindset of people toward work between Japan and the U.S.

In September 1979, motorcycle production started at HAM, and the quality of the first product that came off of the line, namely CR250R off-road bike, was deemed to be as good as that of products made in Japan.

Honda selected the CR25R as the first model for local production because a certain level of demand was expected in the U.S., and also because it was a motocross model with a relatively small number of parts, making it an ideal model to launch and steadily establish the production system, including the proficiency of production associates. This was an approach only Honda could take, as an OEM of both motorcycles and automobiles, that OEMs specializing in automobiles could never imitate.

- In 2021, HAM was consolidated into Honda Development and Manufacturing of America, LLC. (HDMA), which currently produces automobiles as well as automotive engines and transmissions.

Honda Globalization Began with Success in Ohio

In January 1980, only four months after the first motorcycle rolled off the line at HAM, Kawashima announced the plan for Honda to produce automobiles locally in the U.S., a first for Japanese automakers. Everyone knew that Honda had an intention to start local production of automobiles eventually; however, the decision came so quickly that it caused quite an uproar within HAM. An automobile production plant would require a much larger operation scale and investment amount compared to a motorcycle plant. Still, HAM members began working toward the construction of an auto plant, while also working on the installation of a production line for a new flagship motorcycle model, the Honda GL1100 Gold Wing. In such challenging times, what Kawashima said in Japan was conveyed and inspired HAM members in the U.S.: Kawashima said, “Ohio is the lifeline of Honda.”

Kawashima later spoke to the truth of his words: “At the time, one U.S. dollar was worth between 220 and 230 yen. The initial investment amount we put into our auto plant in Ohio was $200 million, which was approximately 45 billion yen. This was when Honda was still striving to become a company worth 1 trillion yen. So, if that initial investment had gone sour, we were in trouble. The company would have gone bankrupt. So, it was no exaggeration. I really meant that Ohio was our lifeline!”

In May 1979, Kawashima delivered a message to all Honda associates, demanding that everyone “abandon the no-play, no-error mentality.” In his message, Kawashima warned Honda against growing into a company that “tries nothing new, and therefore never fails.” He asked Honda associates to maintain their vitality to take on challenges through action, using their bodies even if it would mean getting covered in mud, not just thinking with the head. While demanding associates take on challenges, Kawashima himself made a bold decision as top management and demonstrated his commitment to the success of Honda in Ohio.

For automobile production, a mutually complementary system was established between Saitama Factory’s Sayama Plant and HAM’s new auto plant to cover each other’s production. Serving as a “mother factory,” Sayama Plant sent approximately 300 experts and experienced associates to Ohio to support the initial launch of the new auto plant. In order to build a plant that would take deep root in the U.S. society, HAM set a basic policy to be proactive in installing locally-sourced production equipment wherever possible. This included using steel sheet, plastic, paint and other raw materials procured locally in the U.S. In consideration of differences in quality standards between the U.S. and Japan, it was a challenging choice Honda dared to make. When building a motorcycle plant in Belgium in 1963, Honda experienced some struggles with the establishment of a knockdown parts production system and local procurement of parts. The lessons learned through the experience in Belgium were put to good use in Ohio.

In November 1982, construction of the first Honda automobile production plant in the U.S. was completed. For the line-off ceremony for the first U.S.-made Honda vehicle, the Accord Sedan, Kawashima flew from Japan and spoke at the event. By this time, the importing of Japanese automobiles to the U.S. was a central issue in Japan-U.S. trade friction; therefore, Honda’s local automobile production in the U.S., the first among Japanese automakers, was welcomed by both Japanese and U.S. government officials.

This year, 1982, marked the beginning of rapid growth of Honda auto production in the U.S. In 1986, Honda became the first Japanese company to locally produce automotive engines in the U.S., and Civic production started at HAM in July of the same year. In 1988, in another first, Accord Coupe became the first U.S.- made Honda model exported to Japan, and in December 1989, HAM’s second auto plant (East Liberty Auto Plant) became operational. By shifting from importing to local procurement of parts, Honda made a substantial contribution to the region by creating more jobs at local suppliers.

In 2003, on the occasion of commemorating the 25th anniversary of the establishment of HAM, Honda motorcycles were displayed at the Columbus Airport in the Ohio State Capital, and events were held throughout the region for a week-long celebration started on September 10, the day the HAM motorcycle plant began operation. During this celebration, Honda received messages of appreciation from numerous Ohio community and government leaders.

The commitment Honda made to set down deep roots in the local community turned out to be a great success, and Honda was able to establish a significant presence in the U.S. The success in Ohio proved that Honda Philosophy could transcend cultural and national differences and contribute to people, and became a significant turning point in the global expansion of Honda.

On November 1, 1982, the first Accord rolled off the production line in Ohio.

This vehicle, the first locally produced car in the U.S. by a Japanese automaker, is on display at the Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. In the photo, Kiyoshi Kawashima is standing in the middle with his hand on the hood.

Educating People to Realize a Safe and Healthy

Mobility Society

While offering vehicles with superior environmental performance ahead of other automakers, Honda began working diligently to promote safe driving as well. With the advent of motorization, cars and motorcycles were popularized in society and became an indispensable means of daily transportation for people. In the meantime, since the second half of the 1960s, the number of traffic collisions in Japan had skyrocketed, and traffic safety became a pressing societal issue. Honda had become increasingly self-aware of its mission to halt the rise in traffic collision fatalities not only by improving “hardware” as a manufacture of mobility products but also by spreading “software” in a form of traffic safety education for everyone sharing the road.

Honda safe driving/riding education activities have their roots in training for motorcycle police officers which began in October 1964, at the Suzuka Circuit Safe Driving Training Center. In July 1963, a section of the Meishin Expressway (Nagoya-Kobe Expressway), the first expressway built in Japan, opened to traffic, and the motorcycle police commander of the Chubu Regional Police Bureau, which had jurisdiction over that particular area of the expressway, contacted Honda to consult about how to prevent motorcycle police officers from being killed in the line of duty. That is when Honda began teaching riding techniques to motorcycle police officers at the Suzuka Circuit Safe Driving Training Center under real-world traffic conditions and scenarios. Since 1965, the range of participants in this training session had expanded to include employees of other public agencies and utilities such as the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications (later, Japan Post Group that comprises Japan Post Holdings Co., Ltd., Japan Post Co., Ltd., Japan Post Bank Co., Ltd. and Japan Post Insurance Co., Ltd.), Kokusai Denshin Denwa Co., Ltd. (later, KDDI), Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Public Corporation (later, NTT Group) and electric power companies.

In 1970, the Traffic Safety Promotion Operations was established within Honda to further expand Honda initiatives to train more instructors and promote safe riding/driving throughout Japan. In addition to classroom learning that included lectures on theory, real-world, hands-on training which had been refined at the Suzuka Circuit Safe Driving Training Center was integrated into the instructor training program. Honda established its Traffic Education Center, first in Fukuoka then throughout Japan, and by 1974, the total number of instructors educated by Honda exceeded 10,000, and safe riding/driving education became a nationwide movement in Japan with cumulative participants of surpassing the hundreds of thousands.

In 1972, Honda created a division within the Driving Safety Promotion Center dedicated to facilitating driving safety promotion outside Japan, expanding its safe riding/driving promotion activities to the U.S., Canada, South Korea, Vietnam and Brazil. Moreover, the members of the division participated in various international conferences around the world, and Honda activities, theories and systems for promoting safe riding/driving received high international recognition.

Around that time, the population of motorcycle riders in Japan was on the rise. In response, in 1972, helmet use became mandatory on roads where the maximum speed limit was over 40 km/h. Then, by 1975, separate motorcycle licenses were introduced for small (under 125 cc) and medium (under 400 cc) displacement motorcycles; and in 1978 a move was made to require all riders of 51 cc or larger motorcycles to wear helmets on all roads.

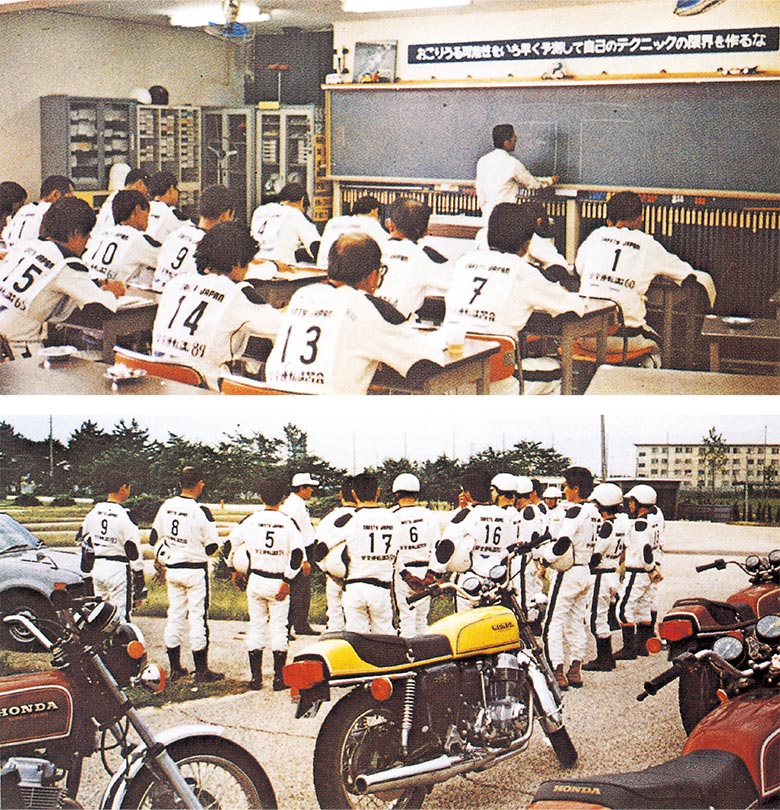

Scene of an instructor training session.

Scene of an instructor training session.

In the 1980s, an unprecedented motorcycle boom occurred, mostly among young people, which provoked an argument that popularization of motorcycles may lead to an increase in juvenile delinquency in parallel with traffic safety issues. Around this time, the number of “bosozoku,” or groups of young people who ride their customized motorcycles and cars with loud exhaust sounds in a rebellious, reckless manner, was on the rise and becoming one of the societal issues in Japan. Against this backdrop, the National Federation of High School PTAs in Japan launched the controversial “Three No’s” campaign, which discouraged students from getting a motorcycle license, riding motorcycles and buying motorcycles. This campaign proposal was followed by the PTA federations of more than half of the prefectures in Japan.

In response to this social trend, Honda launched an initiative called the “Safety Up” strategy to promote traffic safety under its policy – “Rather than keeping young people away from motorcycles, we need to educate them about safety to help them become healthy participants in this motorized society.” Honda believed in the importance of providing more opportunities for people to familiarize themselves with motorcycles from a young age through “Ride and Learn” style educational programs, which would promote the significance and technique of safe riding/driving and also expand the rider/driver base.

While offering more people “freedom of mobility” as a motorcycle and automobile manufacturer, Honda had been taking the initiative, from an early stage of its corporate history, in protecting people from traffic collisions, building a better mobility society and pursuing safety for everyone sharing the road.

The Honda -Yamaha War: A Heated Battle for Supremacy

in the Motorcycle Industry

In 1976, Honda launched a new product, the Honda Roadpal (Honda Express, or NC50, in North America), and created a new genre of vehicle, which was neither a motorcycle nor a bicycle. It featured a bicycle-like frame, small 14-inch tires, a fully automatic transmission that eliminated the need for changing gears. The conventional kick start mechanism was eliminated to achieve a simple design.

Sophia Loren, an Italian actor of worldwide popularity at the time, was cast in a series of advertisements including TV commercials, with the Honda Roadpal marketed primarily toward homemakers and young women with no previous interest in motorcycles. It became a huge hit, and the catchy phrase used in advertisements, “Rattatta,” became a buzzword in Japan.

With the Roadpal, Honda pioneered the “family bike” genre of motorcycles. Kawashima described the thoughts and passion Honda put into the development of Roadpal: “Mentally and physically, motorcycle riding is not all harmful as a kind of sport for young people in a transitional phase of their lives. Rather, there should be something beneficial [...] We created the Roadpal with a determination to offer a lightweight, convenient and simple bike that mothers and homemakers would ride with joy and peace of mind, and introduce to their children based on what they experienced and the fun, convenience, or danger they felt at first hand.”

Honda takes pride in having created Japan's motorcycle culture. By increasing the number of women who would ride bikes, Honda Roadpal helped to broaden the market base for motorcycles and contributed to the healthy growth of motorization with motorcycles.

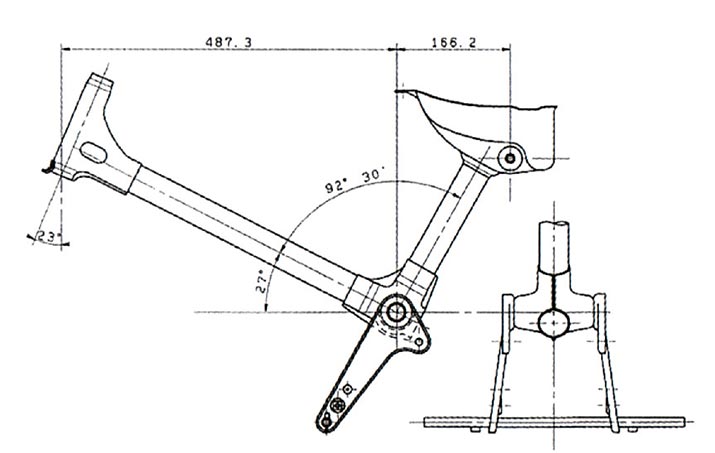

Honda Roadpal (1976), which opened up a new market for motorcycles.

The Roadpal frame featured a design layout like a bicycle frame.

Inspired by the success of the Honda Roadpal, Yamaha Motor Co. Ltd. (Yamaha) and Suzuki Motor Corporation (Suzuki) developed and launched similar scooter models, which eventually led to a scooter boom. Introduction of new models activated the market and generated demand among students and even among riders who were already riding motorcycles, resulting in a continuous increase in unit sales.

During this period when the market changed dramatically and sales boomed, Yamaha saw the opportunity and stepped up its effort to increase its presence in the Japanese motorcycle market. For the six-month period from January through June 1976, the Honda share of total motorcycle shipments was approximately 40%, with Yamaha gaining ground at around 36%. Building confidence, Yamaha declared its intention to take over the leading position in the motorcycle industry.

This was the start of what became known as the “HY (Honda-Yamaha) War.” In response to Yamaha's attempts to seize control of the market by launching a number of new products one after another, Honda began developing new products at a furious pace to uphold its pride as the No.1 motorcycle company in Japan. Including full and minor model changes, Honda developed and launched approximately 50 models each year, while also enhancing the sales force at Honda dealers across Japan. The market share competition increasingly intensified, and neither side was able to back down. To differentiate each other’s products, both companies introduced a broad range of models featuring unique concepts and designs. In the meantime, due to their excessive production expansion plans, both development and production operations fell into turmoil. The market was ravaged by fierce sales competition that drove down the sales price to the limit. Eventually, the development, production and sales operations of both companies became fatigued.

By fall 1982, the overheated sales competition resulted in a large volume of unsold inventories at both companies. In January 1983, when its inferiority had become clear, Yamaha finally announced its desire to end the HY War. At the time, Honda R&D was rapidly developing new mid-size models such as the CB400 and CX500 to take away Yamaha's market share in the U.S., however, Kawashima ordered a temporary suspension of the development of those models in response to Yamaha’s declaration of the end of the HY War.

Ultimately, the HY War was a battle of pride between two motorcycle manufacturers. Although valuable lessons regarding development and production were learned, Honda lost sight of the “Joy of Buying,” one of “The Three Joys” Honda had valued since its founding. Honda learned the hard way that when it loses sight of the “Joy of Buying” for its customers, it also loses the “Joy of Selling” and the “Joy of Creating.” Ultimately, the motorcycle industry gained little from the HY War.