Establishment of Sales and Service Network

in the Automobile Market

Before entering the automobile market, Honda needed to quicky establish a new sales network suitable for automobile sales. For motorcycles, Honda was able to build a sales network relatively quickly by organizing bicycle shops, but Honda had to come up with the best strategy for building an automobile sales network. Even if existed motorcycle shops were willing to sell automobiles, it would be technically impossible for them to handle after-sales services and repairs.

Therefore, Mr. Fujisawa came up with plans to establish a network of service factories (SFs). In this system a division of labor between sales and service was put in place. The dealers would concentrate on sales, and Honda-operated SFs located throughout Japan would handle all after-sale service and repairs.

Additionally, Honda established a separate company named Honda Sales Research Co.,Ltd to support dealers with no previous experience selling automobiles. As with the concept Honda R&D was based upon when it was established as an independent company, Honda Sales Research was established as a company that would apply science to sales activities, and conduct research on sales strategies while also serving as a liaison between Honda and its dealers. This unconventional sales company received around 3,000 job applications from all over Japan and hired 127 sales representatives. Around the same time, Honda also established two more companies: a consumer credit company and used car sales company.

At that time, cars required incomparably more repair works than cars today; therefore, the after-sales service operation played a significant role. Mr. Fujisawa placed emphasis on the importance of enhancing Honda service operations and invested 15 billion yen to build a nationwide Honda SF network. In 1960, when the starting monthly salary for a bank employee with a university degree was approximately 15,000 yen, understandably the purchase of a car was a momentous decision even for the average salaried family at that time. Given the scale of Honda’s automobile business at the time, it was impossible to build a network of large-scale dealerships like Toyota or Nissan; therefore, Honda went its own way and strived to build a sales operation that enabled Honda to serve each and every customer while resonating with their “joy of buying a car.”

The “Three Joys” – The Joy of Buying, The Joy of Selling, and The Joy of Creating – constitutes a fundamental part of Honda Philosophy, and it originated from the company expression Mr. Honda set forth in 1951.

Then, in 1955, Mr. Fujisawa wrote the following in a company newsletter to prompt more accurate understanding of the meaning of The Three Joys: “We must always put the joy of our customers first. Only when our customers feel the joy (of buying), can we feel the joy of selling. As the reward of realizing those two joys, we get the joy of creating. That is the right order.”

The true purpose of the huge investment Honda made to build a nationwide SF network was to realize The Joy of Buying for each and every customer.

Building Suzuka Circuit and Competing in F1:

Advancing and Refining Technologies at the Pinnacle of

Motorsports

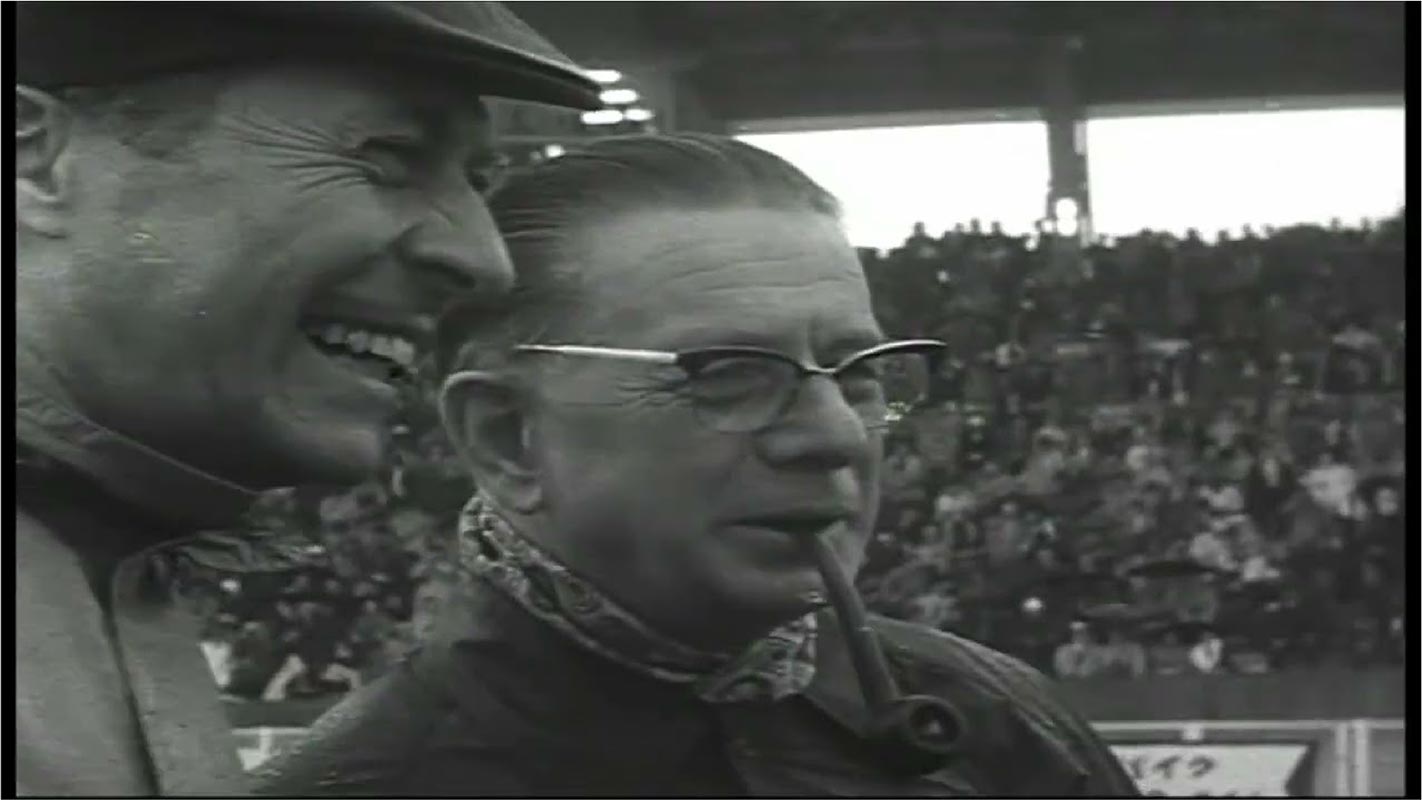

First F1 race at the German Grand Prix (1964)

First F1 race at the German Grand Prix (1964)

Motorsports have been deeply rooted in the Honda corporate culture, and the passion Honda has for motorsports has its roots in Mr. Honda’s love of motorcycles, cars and racing, and his fervent desire to make “the best cars in the world.”

In 1961, Honda achieved a breakthrough in motorcycle racing: winning the Isle of Man TT Races outright both in the 125 cc and 250 cc classes and also winning the Constructors’ Championships in the FIM Road Racing World Championship Grand Prix (currently, the FIM Grand Prix World Championship, also known as MotoGP) in both classes.

Mr. Honda had a strong belief: “Without racing, our vehicles will not get any better. Engaging in fierce competition in front of spectators is the only way to become number one in the world.” Such passion of Mr. Honda for racing led to the construction of Suzuka Circuit, Japan’s first full-fledged race track.

In 1959, Mr. Fujisawa led the project team and undertook the construction of Japan’s first full-scale, fully-paved European-style race track. His vision for the project also included the construction of a large-scale amusement park facility that would serve as a place to promote motorization among teenagers, the future owners of motor vehicles, and also as a place for research and education in the field of mobility technologies.

Moreover, this facility was designed with the theme of “creating a safe facility where people can enjoy riding and driving, where they advance and refine their riding/driving skills without even knowing it.” This theme was set because there were no facilities or opportunities for people to advance their riding or driving skills in Japan at the time. The emphasis Honda placed on safe riding and driving later led to the opening of the Suzuka Circuit Safe Driving Training Center (1964), which was used to train motorcycle police officers, as well as the establishment of the Traffic Safety Promotion Operations at Honda (1970).

Since there was no precedent for building a full-fledged race track in Japan, the project began by gathering information on race tracks in Europe. Among a number of potential sites considered throughout Japan, Honda chose Suzuka not only because of its desirable location, but also because of its positive experience with the city at the time of the construction of Suzuka Factory and the proactive and welcoming attitude the city expressed for the new project.

Upon completing the construction in 1962, Suzuka Circuit hosted its memorable first race: The First All-Japan Championship Road Race Meeting (later, All-Japan Road Race Championship). The spectators were fascinated by the sound and speed of racing machines hurtling past them and realized that a new era of full-fledged motorsports had finally arrived in Japan.

In January 1964, Honda announced its plan to participate in Formula One (F1) racing. At the time, not many people in Japan had heard of F1, and even at Honda R&D, there weren’t too many associates who were familiar with it.

Honda made this major decision to take on challenges in F1 racing, despite the fact that Honda was the newest manufacturer in the automobile industry, and had just introduced its first k-truck and k-sportscar models in the previous year, triggered by the bill on the Temporary Measures to Stimulate Specific Industries, which could have eliminated the opportunity for Honda to enter the automobile market.

Only seven months after the announcement, in August 1964, Honda made its debut in F1 at the German Grand Prix with the RA271, an F1 machine, including the engine and chassis, developed entirely by Honda. For the 1964 season, the results were disastrous – early retirement from two of the three races Honda competed.

In the 1965 season, Honda also competed in the F2 series, a category below F1, but again faced an uphill battle. Still, Honda kept up the fight to overcome mechanical issues one by one with persistence, including a reduction of machine weight, improvement of engine cooling performance and lowering of the machine’s center of gravity. As a result of such efforts, Honda captured its first victory in the Mexican Grand Prix in October 1965.

Mr. Honda spoke at a press conference upon receiving the news of Honda’s first F1win:

“We have a determination to take on the most challenging path as an automaker. That has been our motto. Win or lose, it’s our obligation to pursue the cause of the result, improve the quality and offer safer cars for our customers. [...] Without being carried away by this victory, we will pursue the reasons for the victory and apply more and more successful technologies to our new models.”

Moreover, in F2, despite struggling in the first year, Honda won 11 consecutive races in the second year, 1966.

Honda had been able to dramatically advance performance and technology of its production motorcycle models by applying technologies developed and refined in the intense competition in the Isle of Man TT Races. Building on this successful experience, Honda strategically participated in F1, the most prestigious automobile race series in the world, to make a major contribution to the advancement of the automotive technologies of Honda, Japan and the world.

Suzuka Circuit opens (1962)

Facing Setbacks with an Air-Cooled Engine in both

the F1 Machine and H1300: Conflict Between Mr. Honda

and Young Honda Engineers

While continuing to develop racing machines, Honda had begun taking on the challenge to develop a small passenger vehicle. Mr. Honda was thinking, “If we are going to develop a small car, it has to get the better of Toyota and Nissan, which are way ahead of us.”

For Honda, which had only developed k-cars and compact sportscar models up to then, the development of a small passenger car was much more challenging that it had imagined.

In September 1967, after due consideration of its plans, Honda decided to pursue a product concept that would emphasize both high performance and the affordability of the vehicle. To be competitive enough in the small passenger car market, the new model would be equipped with an engine one rank smaller than competing models. The first set of Honda small passenger models with two engine variations were named the H1300 77 Series and the H1300 99 Series.

While working on the new passenger car, Mr. Honda had already given instructions to develop a new air-cooled engine for F1 machines. His plan was to prove the superiority of the air-cooled engine over a water-cooled engine in F1 racing, before applying it to production models.

Mr. Honda insisted, “The water for the water-cooling is ultimately cooled by the air. Then, why not use air-cooling to begin with? Air-cooled engines eliminate concerns for water leaks and require less maintenance. We only need to address the issue of the high noise level, which is unique to air-cooled engines, and bring it down as low as the noise level of water-cooled engines.”

All motorcycle models Mr. Honda had developed by then were equipped with an air-cooled engine, and the N360 equipped with an air-cooled engine became an unprecedented hit. Based on his experiences, Mr. Honda firmly believed that air-cooling was what made Honda products unique.

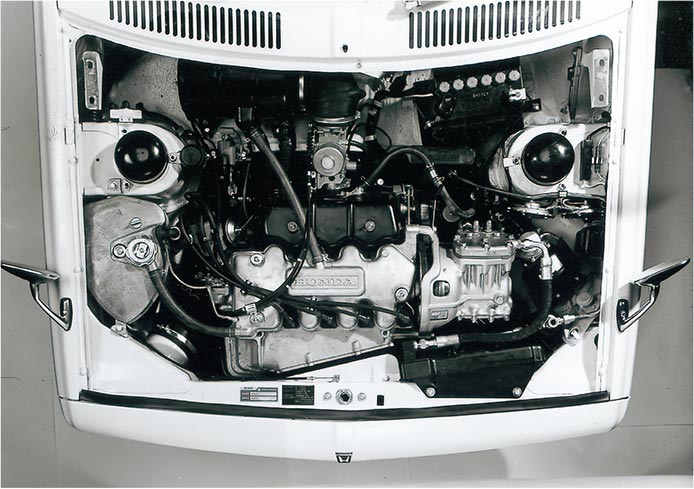

1300 77 air-cooled engine

1300 77 air-cooled engine

On the other hand, young Honda engineers were questioning whether air-cooled engines would be truly suitable for passenger cars of the future. They developed prototypes of air-cooled engines that were as compact and quiet as water-cooled engines. However, the prototype engines experienced a number of heat-related problems such as an increase in the temperature of various engine parts and oils. The prototype engines underwent repeated design changes, but still faced a host of problems, most of which were heat-related, such as the deformation of the cylinder head and oil leaks caused by high heat.

Mr. Honda came by the R&D Center every day and issued a series of rapid-fire instructions directly to each engineer in charge of different parts of the engine development. However, everyone on the team, including project leader Tadashi Kume, had arrived at the conclusion that a water-cooled engine was the only appropriate choice for passenger car engines in the future.

There was no doubt that Honda motorcycles equipped with air-cooled engines were very successful. However, air-cooling worked with motorcycle models at the time, because the engine sizes were small enough to be cooled by the air flow as long as they were moving. However, cooling of automobile engines was a completely different matter. Moreover, it was the time when people started paying more attention to the issues of automobile exhaust emissions, and it was already common knowledge among engineers that water-cooling was the most suitable choice for engines compliance with emission standards as it enabled stable heat management.

No matter how sincerely young engineers tried to convince Mr. Honda, he wouldn’t budge from his conviction that, no matter how difficult the problem, he could somehow harness the power of technology to achieve a breakthrough.

Eventually, at the R&D Center, the project team made a decision to start up a research team to work on water-cooled engines without letting Mr. Honda know.

Air-cooled vs. Water-cooled Engine Debate:

Generational Shift Happening at Honda

Mr. Honda’s burning obsession, the H1300, went on sale in Japan in May 1969.

The H1300 earned great acclaim for its power. In fact, there is an anecdote that Mr. Eiji Toyoda, the fifth president of Toyota Motor Corporation, saw the H1300 on display and said to his engineers, “Honda’s 1300cc engine is generating 100 horsepower. Why can’t ours do that?” Despite such high praise for the engine output, the H1300 did not achieve the sales volume Honda expected.

At the R&D Center, engineers continued their discussions on the theme of “Why isn’t the 1300 selling well?” They identified that H1300 was suffering various issues attributable to the adoption of the air-cooled engine, such as the heavy load put on the front part of the vehicle, uneven tire wear, and exhaust gas that would not comply with the stricter regulations anticipated at the time. With such thorough technological analysis, the engineers made an impassioned appeal to Mr. Fujisawa: “To date, Honda has been pursuing higher rpm and more horsepower with our air-cooled 4-stroke engines. However, in order to comply with the ever-stricter emission regulations of the times, we must take on challenges with water-cooled engines. This is the area Honda can prevail because we have gained full knowledge of the ultimate in combustion inside engines through our challenges in racing activities such as in the Isle of Man TT Races and the F1.” Understanding the earnestness of their appeal, Mr. Fujisawa instructed them to explain their opinions directly to Mr. Honda.

Hideo Sugiura, then the head of Honda R&D, and Kimio Shinmura, then the chief engineer in charge of engine development, went to see Mr. Honda with grim determination and made a direct plea: “Please let us work on water-cooled engines. If we don’t start now, we won’t be able to comply with upcoming emissions standards in time.”

Mr. Honda curtly replied, “Do whatever you want. Just make sure you take care of the water leak issues,” and walked away.

Taking his words as an approval, the R&D Center made a dramatic change of course toward full-fledge development of water-cooled engines and managed to complete a prototype of the new k-car model, the Life, in a short period of time.

In June 1971, Honda introduced the Life equipped with an inline 2-cycliner engine, which was same configuration as the N360 engine, but this time with water-cooling, which significantly improved occupant comfort by eliminating the issues of oil smell and lack of in-cabin heating capability.

There was a reason why Mr. Honda, who was obsessed with air-cooled engines, unexpectedly backed down on his opinion. After listening to the opinion of young engineers, Mr. Fujisawa became certain that Honda would lag far behind competitors in the automobile market as long as it would stubbornly insist on air-cooled engines. Moreover, he also became certain that Honda had high potential to develop low-pollution engines. Based on his belief, Mr. Fujisawa asked Mr. Honda the ultimate question: “Mr. Honda, do you want to stay with Honda as company president, or do you want to stay as an engineer?” After a period of silence, Mr. Honda sheepishly replied, “I will stay as president.”

Mr. Soichiro Honda had led Honda to success as a genius engineer; however, young engineers who grew up learning from Mr. Honda were about to surpass him in both technological skills and knowledge. Including the continuous advancement of automotive electronics, automotive technologies had become increasingly complex, and it was no longer possible for a single genius to control everything.

The two company founders witnessed that young engineers who Mr. Honda nurtured were ready to spread their wings and become the “next Mr. Honda” in the new era.

Developing Low-Pollution Engines for People and for the Earth

The era where automakers competed for higher speed and bigger horsepower, which had been the driving force for Mr. Honda, was gradually coming to an end as society began demanding more environmental and safety measures with automobiles.

During the 1960s, Japan saw the blossoming of motorization. The Meishin Expressway, which connected Nagoya to Kobe in western Japan, opened to traffic in 1963, a year before the 1964 Summer Olympics held in Tokyo, and the Tomei Expressway between Nagoya and Tokyo was fully completed in 1969. As a result of this so-called “my car boom,” the number of personally owned cars in Japan increased from approximately 510,000 units in 1960 to approximately 9 million units by 1970. With this trend, exhaust emission issues began to emerge as a major problem in Japanese society.

In the U.S., the world’s largest automobile market, the Federal Government had already enacted the Clean Air Act in 1963, proceeding with stricter control of vehicle exhaust emissions. In 1970, U.S. Senator Edmund S. Muskie submitted his clean-air bill to Congress, which proposed to institute major revisions to the Clean Air Act of 1963. The U.S. Clean Air Act of 1970 (known as the Muskie Act, especially in Japan) went into effect on December 31, 1970. The Muskie Act stipulated that, starting with the 1975 model year, automobiles should emit one-tenth of the amount of carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrocarbon (HC) compared to the 1971 model year vehicles, and that 1976 and later model year vehicles also should emit one-tenth of nitrogen oxide (NOx) compared to the average emission level of 1971 model year vehicles.

The standards set forth in this new law were very stringent, and in fact, major automakers around the world argued that it would be impossible to meet such standards. In the midst of such trends of the times, Honda engineers pushed forward with the development of low-pollution engines using Honda’s original CVCC*5 technology.

- CVCC: Compound Vortex Controlled Combustion

In the process of the CVCC engine development, Mr. Honda had an exchange with young Honda engineers, which made him realize his limitation. He recalled that exchange in his resignation speech, recounting as follows:

“For example, when I said that the successful development of the low-pollution CVCC engine would give us a chance to stand on the same stating line as other automakers who started ahead of us, one of our young engineers at the R&D Center argued that addressing emission issues should not be done based on the business interest of individual companies, but should be pursued as a part of responsibility the automobile industry must assume in society. His argument opened up my eyes and truly inspired me.”

This was also the time when society started to hold automakers socially responsible for traffic safety. In Japan, the number of traffic accidents reached its peak in 1970, and the situation was described as the “Traffic War.” The number of traffic accidents in Japan reached approximately 720,000 a year, including approximately 17,000 fatalities.

To promote traffic safety, Honda opened the Techniland Suzuka Circuit Safe Driving Training Center and began offering a training program for motorcycle police officers as early as 1964. This training program was later expanded nationwide, mainly with the National Police Agency, and was also extended to include general motor vehicle users. Sparing no effort in promoting safe riding/driving, Honda established the Traffic Safety Promotion Operations in 1970 and further enhanced its activities to promote traffic safety for everyone sharing the road in the motorized society.

Honda had begun taking on challenges in addressing two major issues that the mobility industry still faces today – the environment and traffic safety.

Shifting to Collective Leadership:

Resisting the Law of Perpetual Change

Honda was reaching the end of its founding period, and was about to enter a new phase of business growth. Mr. Fujisawa made Honda R&D independent of Honda Motor to enable it to rise above the law of perpetual change. However, even if Honda R&D would generate the second and third “Mr. Honda” or highly talented engineers, Honda would have no future if there was no one who could recognize and leverage such talent for Honda business. Even if outstanding individuals could somehow be found and nurtured, they would be buried in the depth of the organization. To avoid such loss, Mr. Fujisawa thought that it would be desirable to install a “collective leadership” of managing directors.

Based on his belief, in 1964, the year Honda made inroads into the automobile market, Mr. Fujisawa introduced the so-called “Big Boardroom System” where all board members, except Mr. Honda, shared one big office space within the head office in Yaesu, Tokyo. Having all board members in one room spontaneously invigorated the exchange of opinions among board members.

Through such active communication and exchanges, board members further enhanced mutual trust with each other and deepened their knowledge and interests in fields other than those they were already familiar with Moreover, in order to instill a sense of commitment as top management into the minds of those directors, Mr. Fujisawa made all directors take turns to be in charge of labor affairs including negotiating with the company labor union.

In 1970, four managing directors, namely Kiyoshi Kawashima, Kihachiro Kawashima, Michihiro Nishida and Takao Shirai, were promoted to senior managing director, further strengthening the system of collective leadership.

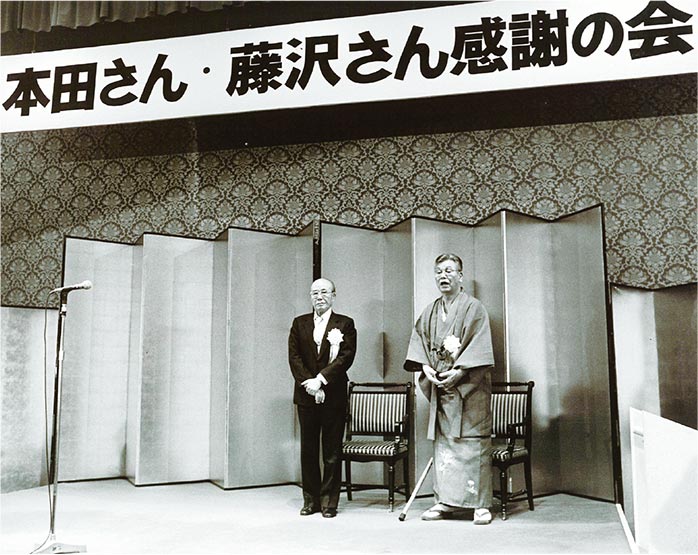

By around 1972, Honda was being managed under the leadership of the four senior managing directors. In March 1973, Mr. Fujisawa told Nishida, one of the four senior managing directors, who was in charge of administration, “I will leave the company at the end of this fiscal year. So please inform President Honda of my decision.”

As soon as he heard of Mr. Fujisawa’s intention to retire, Mr. Honda told Nishida, “I’m only here as president because of Takeo Fujisawa. If the executive vice president Fujisawa is quitting, then I am going to quit with him.”

After his retirement was officially decided, Mr. Fujisawa happened to see Mr. Honda at one of the meetings he attended. Mr. Fujisawa described the scene as follows:

(Mr. Honda) signaled me with his eyes to come over, so I went along with him.

“It was all right," he said to me.

“Yes, it was all right," I responded.

“We had a happy time," he said.

“Yes, I had a really happy time, and I thank you from the bottom of my heart,” I said.

Then, Mr. Honda said, “I thank you, too. We had a great life, didn’t we?”

“That was the end of o conversation about our retirement.”

Twenty-five years had passed since the founding of Honda, and twenty-four years since that post-war summer day when the two met for the first time.