Establishment of Suzuka Factory:

the First Honda Mass-Production Factory

Mr. Fujisawa had again come up with a clever sales strategy for the Super Cub. This time, he approached a wide variety of local business owners ranging from lumber dealers, dry goods stores and Shiitake mushroom farmers based on his out-of-the-box idea: “Selling motorcycles requires after-sales services. So, we will ask local business owners who are conducting their business while taking root in their respective regions, to sell our product.”

Much like the “direct mail” strategy Honda took for sales of the Cub Type-F in the early 1950s, a large number of letters were sent out. Approximately 600 local shops were selected from the 3,500 applications that came in. Even after the first round of selections, more applications continued to pour in, and the number of dealers was doubled quickly.

On top of that, Mr. Fujisawa embarked on a major project to achieve the monthly sales target of 30,000 units. He went ahead and purchased 695,000 square meters of land in Suzuka City, Mie Prefecture and began construction of the first full-fledged Honda mass-production factory. Before starting the project, Mr. Fujisawa conducted research on factories around the world, and then developed a plan to build a factory on a vast scale, breaking with conventional wisdom. Honda, a company with only 1.44 billion yen in capital at the time, made a decision to build Suzuka Factory with an estimated construction cost of between 7 and 10 million yen.

Mr. Fujisawa had three basic policies: build a mass-production factory that would set a good example for the future; set no upper limit on the amount of investment, but recoup the initial investment within two years; and build close ties between the factory and the local community.

Once the decision was made to build a factory in Suzuka, Honda took a wide range of measures to establish close ties with the community. Such measures included investment in road widening, streetlight installation and the addition of traffic signals in the neighboring area, as well as donating a gymnasium and automobiles to the city. In addition, company housing and dormitories for the associates of both Honda and affiliated companies were strategically dispersed throughout the areas surrounding Suzuka City.

Mr. Fujisawa’s thinking behind these measures was to enable Honda factory to take root in the community as a “citizen,” and become the starting point of the establishment of a society where businesses and local community co-exist and co-prosper. His policy to “set no upper limit on the amount of investment, but recoup the initial investment within two years” exuded his business philosophy.

Although Suzuka Factory was built as a dedicated Super Cub production plant, the future introduction of an automobile production line was already factored into the factory layout from the beginning. By maintaining the premise that this factory would be dedicated to Super Cub production, Mr. Fujisawa had the company commit to the early recouping of the construction cost, which enabled Honda to lay the groundwork for future automobile production, which was still an unknown area of business for Honda at that time.

The Suzuka Factory began its operation in April 1960, and established a monthly production capacity of 60,000 units by November of the same year. In 1962, Honda’s annual motorcycle production volume reached 1,055,000 units.

Entering the U.S. Market:

Taking on the Most Difficult Challenge First

In addition to the further expansion of the sales channel for Super Cub, exports would be essential for Honda to strive for a major leap forward. Due to its close proximity to Japan, Southeast Asia was the most likely candidate for the first export destination. For most people it was only logical for Honda to export first to Southeast Asia, then to Europe and, finally, to the U.S.

However, Mr. Fujisawa had a different logic. He believed that the U.S. was the center of the world economy and, thus, if Honda could cultivate demand there, success in the global market would be achieved at once. He insisted that the Honda spirit was about taking on the most difficult challenge first. Over the objections of some stakeholders, Mr. Fujisawa chose the U.S. as the first export destination for Honda.

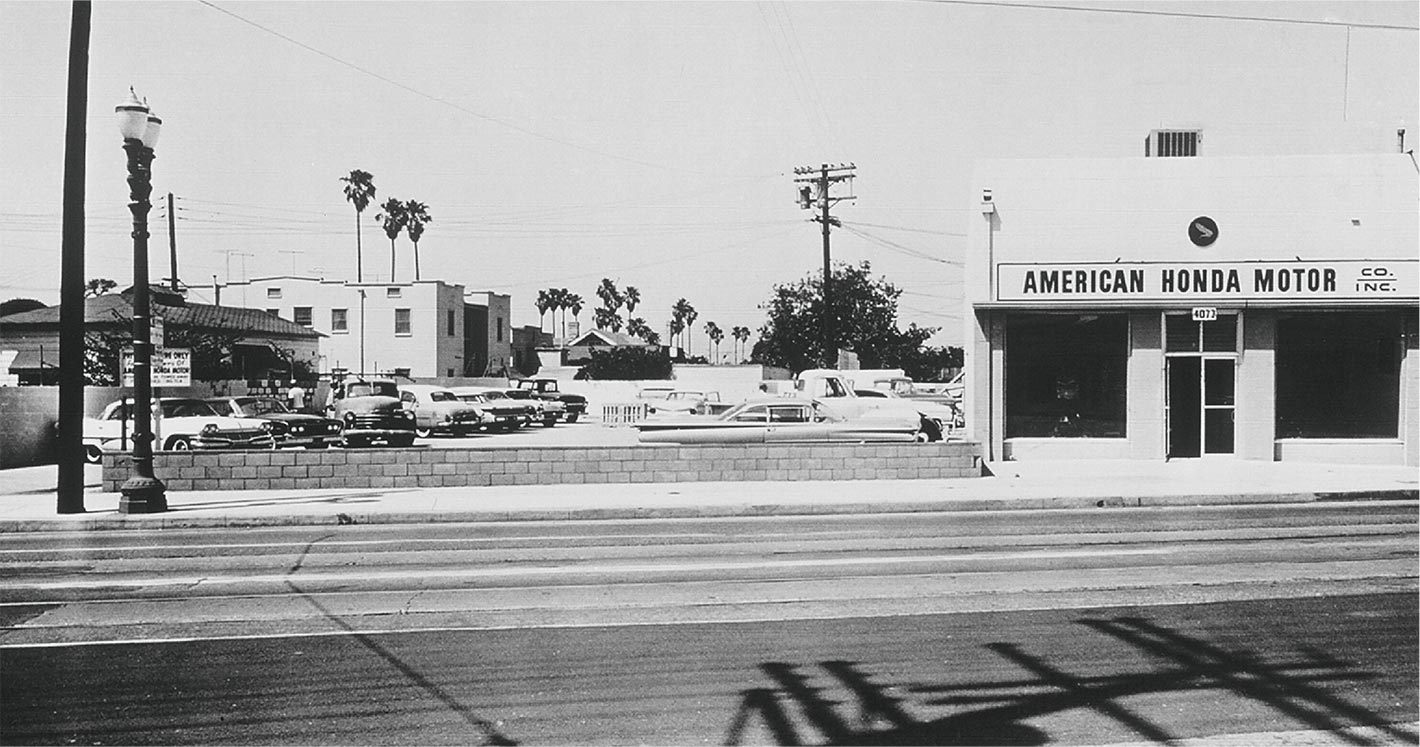

In June 1959, American Honda Motor (AHM) was established in Los Angeles. Honda only sent three staff members from Japan to set up and start the new operation based on the belief that any company that would want to take root and conduct business in a foreign country should establish an operation where locally-hired people would enjoy working and play leading roles.

American Honda Motor Co. at the time of establishment

For Honda, with no brand recognition at that time, cultivating the U.S. market became a very trying time. In the U.S., automobiles were the mainstream means of transportation for people, and motorcycles had a negative image of being associated with outlaws. Some motorcycle enthusiasts were derided as “black jackets” for their fashion style, and motorcycles did not have a wholesome image among the general public.

Industry-wide motorcycle sales in the U.S. at the time, stood at approximately 60,000 units per year, mostly large and heavy motorcycle models with engine sizes of 500cc or more. The initial strategy of AHM was to start selling the Benly 125 and the Dream 250 and 300, and then later add Super Cub in the lineup to further cultivate the market. However, the Benly and Dream models experienced an engine issue and all units were returned to Japan at the direction of Mr. Fujisawa, a commitment to quality that made a positive impression on Honda dealers. In the face of this reality, customers began discovering the Super Cub (Honda 50) and it became a surprise hit, the main product for Honda in America.

In an era when the exchange rate was fixed at 360 yen to the dollar, AHM decided to take a bold advertising strategy at the immense cost of $5 million and launched a massive advertising campaign with the catchphrase, “You Meet the Nicest People on a Honda,” in LIFE magazine, one of the most influential photojournalism magazines in the U.S. at the time, as well as other prestigious magazines such as Time and Look.

LIFE magazine ran a feature article titled “America in Love with Honda.”

The magazine with more than 7 million in circulation, which was serving a role as an opinion leader in the U.S. at the time, wrote that Honda motorcycles had brightened people’s daily lives and changed the mindset of people in America.

In contrast to the intimidating image previously associated with motorcycles, the Honda 50 conveyed a cheerful, healthy and peaceful image. American people became fascinated by the new lifestyle Honda brought about, and the Super Cub quickly became explosively popular. Annual sales volume of Honda 50, which was 84,000 units in 1963, exploded to 268,000 units in 1965, firmly establishing the Honda brand image in the U.S. market.

In building its sales and service operations, AHM followed the same approach as Honda in Japan. AHM sent direct mail to sporting goods stores, motorboat and fishing equipment shops, and introduced its motorcycle products while also introducing motorcycling as a new recreational activity for a broader range of people. Moreover, AHM encouraged existing motorcycle dealers to refurbish their stores and completely change the conventional image of motorcycle shops as dark and greasy.

AHM strived to attract young people and families and fundamentally transform the existing culture surrounding motorcycles. In other words, instead of merely introducing just another motorcycle model. Honda offered a completely new mobility product, the Honda 50. That was the key to success. Teenagers who made up a large portion of Super Cub customers later became the main customer segment for the Civic, and then contributed to the success of the Accord as well, which enabled Honda to grow its business in the U.S. market.

Building a Factory in Belgium:

“Good Products Know No National Boundaries.”

Based on the experience of establishing a local operation in the U.S., Honda had gained the confidence to make a leap as an international company. Fueled by such confidence, Honda made inroads into Europe, where it already had some recognized as a manufacturer of outstanding technology, which was proven through participation in the Isle of Man TT Races.

At the time, motorcycles were serving an important role in Europe as a means of transportation for everyday people. In fact, the European market accounted for 85% of all motorcycles registered outside Japan, and annual motorcycle production volume in Europe was already as large as 2 million units.

In 1961, European Honda Motor GmbH (EH) was established in Germany, and in the following year, Honda Motor (later Belgium Honda BH) was established to be the first Honda production factory outside Japan. The Honda strategy was to build a structure to produce its products in Belgium and sell them within the ECC (the European Economic Community, later the European Union) through EH. Having a local production factory within the EEC had distinct advantages in terms of tariff incentives, as well as production and logistics costs, and was expected to boost Honda sales competitiveness.

In order to make inroads into the moped market, EH launched a new Super Cub-based, motorcycle-like moped model, C130. However, cultivation of the moped market didn’t go as planned for two main reasons. One was that EH could not change preferences of European customers who wanted more bicycle-like moped models. The other was the difficulties Honda faced in procuring parts suitable for original Honda designs and technologies. Furthermore, the overconfidence – If we make them, they will sell – resulted in excess inventory.

The experiences and reflections from this trying time in Europe provided Honda with invaluable lessons, which were applied to the subsequent expansion of Honda operations outside Japan.

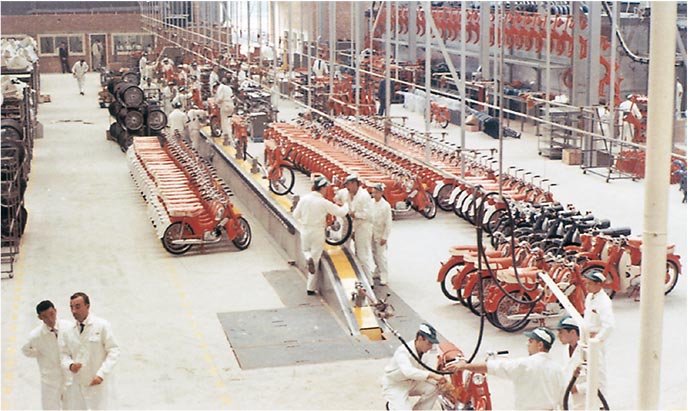

Production at Honda Motor in Belgium

Production at Honda Motor in Belgium

In Asia, Honda first opened a representative office in Singapore in 1962 and conducted thorough market research on various factors including trends in local demand and economic conditions in each country in the region. Baset on the research results, in 1964, Honda established the Asian Honda Motor Co., Ltd. (ASH) in Thailand as its first motorcycle sales company in Asia.

Emerging countries were imposing severe restrictions on the imports of finished vehicles to protect and foster their domestic industries. Therefore, jointly with local partners, Honda established Thai Honda Manufacturing Co., Ltd. (TH), as a plant where knock-down (KD) kits were assembled to produce finished motorcycles.

Honda adopted a strategy to evolve its business with a view to fostering domestic industries in Thailand. In the pursuit of the shared goals of Japan and Thailand, Honda placed emphasis not only on its business but also on employee benefits, which deepened the bond between Honda and the local community. The success of ASH and TH became an exemplary case of making inroads in emerging markets and laid the important milestone in the establishment of Honda as a truly global brand.

In 1968, when Honda reached the 10-million-unit cumulative motorcycle production milestone, Mr. Honda said, “I am very pleased to see my belief that ‘good products can overcome any barriers and enter into any markets’ was perfectly demonstrated by your own hands, arms, brains, and bodies.”

From this point onward, Honda's ideals in monozukuri or product development and manufacturing began truly transcending national boundaries and spreading throughout the world.

Establishment of Honda R&D Co., Ltd.

with an Eye Toward the New Era

Honda R&D Center is completed (1961)

Honda separated its engineering design and research divisions and established an independent company, Honda R&D Co., Ltd., in 1960, the same year the Suzuka Factory was completed. What Mr. Fujisawa intended to achieve by pursuing the founding of this independent R&D company was to create a collective capability of Honda engineers for that time in the future when the one genius, namely Mr. Soichiro Honda, would retire.

In 1956, four years prior to the establishment of Honda R&D and in the midst of developing the concept for the Super Cub, Mr. Fujisawa had already begun to feel that no company can escape the law of perpetual change, and Honda would be no exception. He was thinking that, in this world, there was a law that all wealth and power eventually comes to an end. Honda was undergoing a period of rapid growth, but Mr. Fujisawa was already anticipating the future when Honda would be defeated by newcomers to the market and the time would come when Honda would perish.

In an attempt to find a way to resist this law, Mr. Fujisawa paid attention to the respective functions and roles he and Mr. Honda assumed in achieving a significant breakthrough during the early years of Honda. Then, Mr. Fujisawa came up with an idea to create an organizational structure that could somehow take over the role played by Mr. Soichiro Honda, who had long been pursuing technologies and value that would help people and society, rather than prioritizing short-term profits and current circumstances. Mr. Fujisawa redefined the role of Honda Motor as executing production and sales measures and generating profit. He established a structure where divisions responsible for research and development can concentrate on the “creation of new value” as a separate company independent of Honda Motor.

As an independent company, Honda R&D could work on projects from a longer-term perspective without being swayed by short-term requests from sales, production and other divisions of Honda Motor. The key factors that enabled Honda, which started up as a small factory in Hamamatsu, to become a global company was the power and momentum generated by Mr. Honda and Mr. Fujisawa as they complemented each other’s strengths and weaknesses.

Mr. Fujisawa believed that if the company could build a deeper pool of talented engineers by offering an environment where engineers could immerse themselves in research, the company could keep creating popular products that would become a source of the future growth of Honda, even after Mr. Honda would eventually retire and leave the company. Thus, the organizational structure of Honda R&D was designed with a primary focus on creating a system that could foster and enhance the collective capability of engineers to replace a single genius.

Taking on Challenges to Enter the Automobile Market

on the Brink of Losing the Opportunity

Ten years after the end of WWII, the wave of motorization (popularization of automobiles) was about to hit Japan. In 1955, the Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI, later, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry) announced a so-called “People’s Car Concept” - four-seater with a top speed of 100 km/h, and prices of less than 250,000 yen - to encourage the production of automobiles for the mass market in Japan.

A series of new models in line with the People’s Car Concept was introduced in Japan around the same time: Suzuki Motor introduced the Suzulight Series K-car model in 1955; Daihatsu Motor introduced the Midget three-wheeled k-truck in 1957; Fuji Heavy Industries (later, Subaru) introduced the Subaru 360 four-wheel k-car in 1958; and Toyo Kogyo (later, Mazda) introduced the Mazda R360 Coupe four-wheel k-car in 1960.

In light of the significant economic growth the U.S. had achieved through the rapid growth of the automobile industry, then the Japanese Prime Minister Ikeda, who had initiated the “Income Doubling Plan” in 1960, calling for the doubling of Japan’s real GDP in 10 years, was eager to further promote the growth of the automobile industry in Japan.

Even though Japanese companies at the time were protected by high tariffs, trade liberalization would be inevitable. As soon as the automobile trade would be liberated, the “Big Three (General Motors, Ford and Chrysler) in the U.S. were expected to move aggressively into the Japanese market. Preparing for such a scenario, the Japanese government had recognized the need to proceed with the consolidation of Japanese automakers and enhance their competitiveness.

In May 1961, the MITI announced its fundamental policy for automobile industry administration (later becoming the bill on the Temporary Measures to Stimulate Specific Industries), which included an idea to consolidate Japanese automakers into three groups. This meant that the Japanese government would pursue the elimination and consolidation of existing automakers and restrict new entrants.

By then, rumors of the entry of Honda into the automobile market had been going around within the industry for some time; however, both Mr. Honda and Mr. Fujisawa had a vision to first solidify the company’s foothold in the motorcycle market, and then enter the automobile market after narrowing the gap in business strengths with Toyota and Nissan.

At the time, Honda had only a slim chance of succeeding in the automobile market, not only because the company lacked capital, but also because it lacked technological accumulation. Understanding where it stood, Honda was waiting for the right time to make the move while continuing to build prototypes of its future automobile models.

However, if the bill proposed by the MITI had been signed into a law, Honda would lose its opportunity to enter the automobile industry. Mr. Honda heatedly argued that free competition in Japan was essential to foster international competitiveness of Japanese companies; however, such an argument could not stop the movement toward the submission of the bill.

In January 1962, the year following the MITI announcement, both Mr. Honda and Mr. Fujisawa attended a New Year’s press conference and formally announced the entry of Honda into the automobile industry. Honda also announced that the unveiling of prototype models would take place at the annual gathering of all Honda dealers, a so-called “Honda Meeting” to be held in June, to coincide with the completion of the Suzuka Circuit.

Introducing First Automobile Models in Two Categories:

K-Sportscar and K-Truck

Sports 360 sports car, Sports 500 sports car, and T360 k-truck exhibited at the 9th Japan National Auto Show (Harumi, Tokyo) (1962)

Sports 360 sports car, Sports 500 sports car, and T360 k-truck exhibited at the 9th Japan National Auto Show (Harumi, Tokyo) (1962)

Honda entered the automobile market with a k-sportscar and a k-truck.

Mr. Honda believed that Honda should cultivate new demands for automobiles rather than competing head-on with existing automakers. Based on his belief, Mr. Honda insisted on developing sportscars, which had not yet gained full-fledged popularity in Japan, with the fostering of a motorsports culture in mind. Mr. Fujisawa, on the other hand, proposed to develop a k-truck based on his analysis that commercial-use vehicles would account for the majority of the demand for automobiles in Japan, and in consideration of the ease of sales at motorcycle dealers.

The decision to develop both a k-sportscar and k-truck was made strategically to gain a foothold and track record that would enable Honda to enter both the mini-vehicle group and mass-produced vehicle group of the three groups that the MITI was trying to establish.

At the Honda Meeting, which was held at the soon-to-be-completed Suzuka Circuit located near the Suzuka Factory, it was Mr. Honda who dashingly appeared before the crowd driving a bright red sports car, the Sports 360. It was the moment Mr. Honda’s childhood dream finally came true of driving a car that he had built on his own.

In October of the same year, Honda exhibited the two sportscar models, namely the Sports360 and the Sports500, as well as the T360 k-truck at the 9th All Japan Motor Show, which drew more than 1 million visitors for the first time. The Honda exhibit created a huge sensation both inside and outside Japan. The T360 boasted sportscar-like performance, which was not typical for k-trucks, and the Sports500 realized a top speed of 140 km/h with its 500 cc engine, far exceeding the performance of any 1,000 cc models of Japanese automakers at the time.

Although the bill on the Temporary Measures to Stimulate Specific Industries was repealed in the end, it triggered the start of Honda’s challenge as an automaker.

The N360: First Honda Passenger Car Became the Origin

of the “M/M Concept”

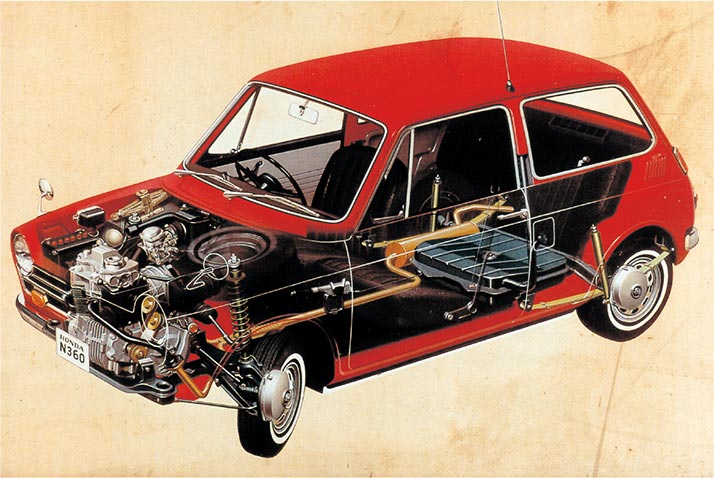

As a latecomer to the automobile industry, Honda needed to boost its brand image as quickly as possible, and the N360, the first Honda passenger car model released in 1966, enabled Honda to promptly do so.

The N360 completely overturned the conventional image people had of k-cars at the time with its sporty “two-box” design and vehicle performance equivalent to a compact car, including the maximum power output of 31 horsepower and a top speed of 115 km/h.

Moreover, a cabin spacious enough to comfortably seat four adults was realized by placing the fuel tank underneath the rear seat and the spare tire in the engine compartment. In addition, the N360 featured large windows for good visibility and even a shock-absorbing steering wheel, a high-end feature only seen in Mercedes-Benz and Porsche models at the time.

Furthermore, instead of a 2-stroke engine that was typical of the day, Honda adopted a 4-stroke overhead camshaft (OHC) engine with high fuel efficiency and cleaner emissions. Developed based on the air-cooled two-cylinder engine Honda had technologically matured by then, the N360 eliminated the concern for water leaks, which was a typical issue with water-cooled engines at that time. This also made N360 attractive for customers.

In Japan, the year 1966 is often referred to as the first year of motorization and the first year of the popularization of personal cars, and the market for 1,000 cc-class compact cars was booming. However, in light of the national income level of Japan at the time, Mr. Fujisawa knew that a passenger car would still be a major purchase for most families, and he forecasted that Honda could sell at least 10,000 units per month if it could come up with a vehicle that comfortably seats four adults with some cargo space, and offered it in the 300,000-yen price range, which was comparable to an average annual family income at the time.

N360 perspective drawing

N360 perspective drawing

Mr. Fujisawa’s sales forecast turned out to be absolutely accurate. The N360 became extremely popular as soon as it launched, and Honda quickly captured the leading position in the k-car category.

Something that should never be overlooked about the N360 is that it was the model where Honda’s original “M/M concept” started. The M/M (Man Maximum, Machine Minimum) concept calls for maximizing the cabin space available for people and minimizing the space required for the powertrain and the engine compartment. While ensuring excellence in dynamic performance as a premise, the N360 was designed with thorough pursuit of the joy and value the customers gain from their experiences and uses of the N360. At Honda, such value to the customer was viewed as a part of vehicle performance.

This basic approach to Honda car design was clearly influenced by a basic approach to and know-how of motorcycle design. Due to the nature of the motorcycle’s dynamic characteristics as a vehicle, it consists only of a powertrain, wheels and a seat, and without a cabin the powertrain components must be designed as compact as possible.

The Honda M/M concept, which calls for maximizing the space available for people and minimizing the space required for mechanical components, has been passed down from generation to generation in the various Honda products that have come after the N360.