Honda Carries the Torch with Its Own Hands

At the time, Honda was proceeding with development of the Cub F-Type, the latest version of its auxiliary bicycle engine, at its factory in Tokyo. Featuring a round, white fuel tank and a bright red engine, the Cub F-Type was innovative not only in technology, but also in design. Its sleek appearance when mounted on a bicycle created a friendly atmosphere for everyone.

With the Cub F-Type, Mr. Fujisawa executed a strategy which resulted in a quantum leap in Honda’s domestic sales network.

Cub F-Type (1952)

Cub F-Type promotion

Cub F-Type promotion

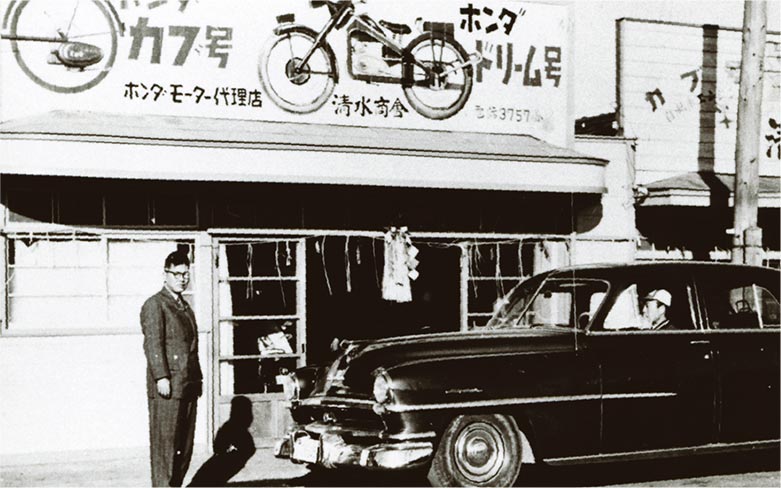

Takeo Fujisawa’s Cub F-Type direct mail campaign established a unique sales network, mainly through bicycle dealers

Takeo Fujisawa’s Cub F-Type direct mail campaign established a unique sales network, mainly through bicycle dealers

The previous strategy of assigning a large number of sales representatives for dealer development and the expansion of the sales network inevitably required a lot of time and money. Honda, which just barely made it from a startup to a small business, didn’t have deep pockets to fund substantial sales costs. After mulling over more efficient ways of selling the Cub F-Type without spending a lot of money, Mr. Fujisawa came up with the idea of contacting every bicycle store in Japan at once. The sales team sent out a “letter,” what is now called direct mail, to more than 50,000 bicycle shops throughout the country.

Written by Mr. Fujisawa, the letter was a masterpiece of salesmanship: “After the Russo-Japanese War, your ancestors made the courageous decision to sell imported bicycles... However, customers are now looking for bicycles with engines. Honda has created such an engine. If you are interested, please contact us.”

Replies came pouring in from more than 30,000 bicycle shops throughout Japan. The sales team immediately sent a follow-up letter to each of these 30,000 shops, saying, “We will send one unit to each shop in the order of received applications. The retail price is 25,000 yen, but we have set a wholesale price of 19,000 yen. Payment can be made by money order or wire transfer to the Honda account at the Kyobashi Branch of Mitsubishi Bank*2.”

Normally, small local bicycle shops would be reluctant to make an advance payment to an unfamiliar company. Being well prepared to address such a concern, Mr. Fujisawa, had asked Mitsubishi Bank, as a favor, to send out a letter signed by the Kyobashi Branch manager, saying, “Please use the Kyobashi Branch of Mitsubishi Bank to transfer money to Honda, one of our customers,” providing confirmation of Honda’s credibility.

The response rate was excellent. Nearly 5,000 shops sent advance payments immediately, and the number of shops eventually totaled 15,000. Thanks to Mr. Fujisawa’s strategy, Honda built its own nationwide sales network in a short period of time, without much investment.

At the same time, Mr. Fujisawa kicked off a dynamic PR campaign, something unprecedented in the motorcycle industry. Honda staged a spectacular parade of fifty female dancers from the Nippon Theater (Nichigeki) Dancing Team, then at the height of its popularity, riding on the Cub F-Type through the streets of Ginza district in Tokyo. Media reported this remarkable event, and the name “Honda Cub Type-F” spread quickly throughout Japan, gaining recognition as an easy to ride engine-powered bicycle for any riders, including women. Moreover, around this time, Mr. Fujisawa also introduced an installment sales system, that ensured monthly payment collection through the use of promissory notes.

In later years, Mr. Fujisawa said, “Honda is a company that would always carry our own torch with our own hands.”

Honda assesses market trends, makes production plans, procures materials based on those plans and places orders with suppliers. All information is in its hand, and Honda has to make its own decisions. Rather than following somebody else’s lead or riding on the coattails of other manufacturers, Honda must carve out its own path from scratch in a way that it believes in. This attitude has always been the foundation of Honda’s management philosophy, which has supported and led the growth of the company. The creation of its own sales network achieved under the leadership of Mr. Fujisawa represented the first steps Honda took in this direction.

- Later Mitsubishi UFJ Bank

The Best in the World Is the Best in Japan:

Making Massive Investment in Imported Machine Tools

For Honda to carry its own torch, there was one critical obstacle that needed to be overcome: in-house production of high-quality parts.

At the time, less than 20% of the parts of Honda products were made in-house by Honda. Even if Honda had boasted that it would strive to become the number one motorcycle manufacturer in the world, there was no way to achieve that goal as long as Honda kept purchasing and assembling parts made with low-precision prewar machine tools. Based on this belief, Mr. Honda and Mr. Fujisawa committed themselves to have Honda make the leap to become a manufacturer equipped with state-of-the-art production machines and facilities.

Backed by strong sales of the Dream E-Type and Cub F-Type, Honda undertook a massive capital increase. Then, in October 1952, Honda decided on the plan to purchase imported machine tools that would cost 450 million yen in total in the currency value at that time (which was one-sixth of the value of today’s currency). Incidentally, Honda's capital value at that time was only six million yen even after the capital increase.

Around the same time, Honda built three separate production plants capable of integrated manufacturing of both engines and bodies: one in Shirako, Yamato-machi, in Saitama Prefecture just northwest of Tokyo (later the town of Shirako in Wako City), and two in the towns of Aoi and Sumiyoshi in Hamamatsu City, down in Shizuoka Prefecture. The total investment, including production machinery, amounted to nearly 1 billion yen. The scale and speed of this expansion were absolutely unprecedented in any industry in Japan at that time.

For the purpose of market observation and procurement of machine tools, Mr. Honda and Mr. Kawashima made their first trip abroad to the U.S. and Europe, respectively.

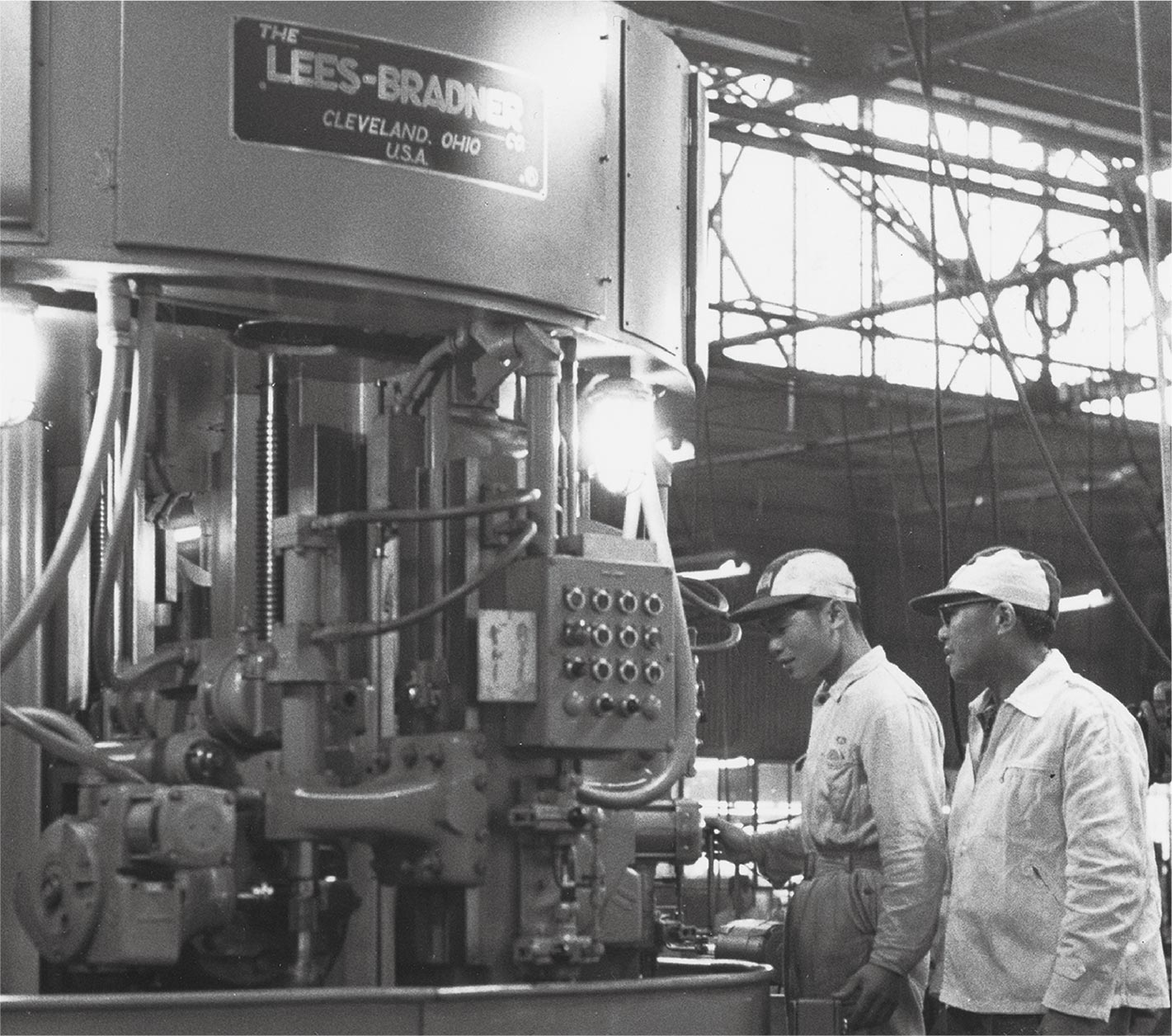

The machine tools Honda purchased during this period played a major role in raising the precision of parts and the competitiveness of Honda products to world standards, while also being instrumental in the development of new models.

Soichiro Honda (right) with machine tools purchased from the U.S.

Facing the Biggest Crisis Since the Founding of Honda

Soon after making such a substantial investment, however, Honda faced the biggest crisis since its founding. Four key products of Honda at that time were saddled with a host of complex problems all at once. Sales of Juno had been struggling due to the issues of excessive weight, handling instability and insufficient cooling of the engine. Sales of Cub F-Type lost momentum due to increased competition and changes in customer needs. The Dream 4E which gained increased engine displacement was facing carburetor problems. On top of all these issues, the new Benly J-Type, a business bike, also got a bad reputation due to noise issues.

Honda temporarily suspended sales of the Dream 4E, resulting in a large volume of inventory. Around the same time, the Korean War ended in an armistice, which brought an end to the special procurement demands of U.S. forces, resulting in a cooling down of the Japanese economy. Under such circumstances, Honda fell behind on payments for imported machine tools, in which it had invested a huge amount of money. Mr. Fujisawa requested Honda manufacturing partners to allow a delay in some payments to them. Mr. Fujisawa also paid a visit to Mitsubishi Bank, the main bank Honda used for financing, to make a full disclosure of the issues facing the company and to ask for their support.

Despite the fact that a labor union had been formed the previous year, the amount of the year-end bonus Mr. Fujisawa proposed was one-fifth of the industry average at that time. Mr. Fujisawa stood before the assembled 1,800 union members and told them with a pleading tone of voice, “Even if the company was able to increase the bonus amount by a little bit more, if the company later goes bankrupt, as the top management, I would feel terribly sorry that I didn't try harder to negotiate better. Instead, I would like to have another round of collective bargaining sometime around March of next year, when I expect our sales will go up.” Fully understanding Mr. Fujisawa’s feelings, all union members responded with thunderous applause, “Yes, we’re counting on you! We're counting on you!”

Meanwhile, Mr. Honda and the team of engineers worked intensively and solved the issue facing the Dream 4E, which enabled the model to regain its originally planned performance. Eventually, the Dream 4E achieved the highest production volume among all Dream series models. Extensive improvements were also made to the Benly J, which became more popular with each passing year. On the other hand, Honda discontinued the production of the Cub F-Type, and production of the first-generation Juno also ended about a year and a half after the market introduction. However, the polyester resin technology developed for Juno was kept alive and revived about three years later as part of the epoch-making design of the Super Cub C100.

Moreover, in spite of this business crisis, Honda made the decision to compete in the world-renowned Isle of Man Tourist Trophy (TT) Races, as well as in several races in Japan.

Sowing the Seeds of Tomorrow’s Flowers

The Isle of Man TT Races, then the pinnacle of the world’s motorcycle races, have been held nearly every year for over hundred years on an island in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland.

In March 1954, Honda proudly issued the Declaration of Entry in the Isle of Man TT Races. In the Declaration, Mr. Honda stated, “... I thought I was seeing the world, but now I realize that, inevitably, I had been far too preoccupied with the current situation in Japan. The world is now advancing at a tremendous speed.”

Mr. Honda came to this realization based on the fact that Honda team was completely outclassed by foreign competitors in an international motorcycle race held in São Paulo, Brazil, two months prior to the issuance of the Declaration.

“If we have yet to catch up with the world, then we need to get out there to face the world.” This was Mr. Honda’s logic.

Moreover, Mr. Honda stated, “...The mission of our Honda is to enlighten the world about the strength of Japanese industry.” Also, the letter addressed to external parties such as distributors, dealers, manufacturing partners and mass media, included a profound message indicating that Mr. Honda was looking far ahead and hoping that Honda’s success in this prestigious race would open the door for the Japanese automobile industry to begin exporting products. The dream of Honda’s two founders was to realize a company with a global presence.

Three months after the declaration, Mr. Honda embarked on a trip to the U.K. and the Isle of Man, to observe the race. What he saw there shook him to his core. Top-class racers from European countries such as Germany and Italy were competing for speed with machines that generated three times the horsepower of the Honda engine despite the fact that the cylinder capacity was the same. It wasn’t just the machine as a whole, but the performance of individual parts such as tires and chains were far superior to anything available in Japan. Mr. Honda was completely astonished. He later said that he even regretted his declaration to compete in this race while watching machines fly by that far exceeded his imagination.

However, after a decent night’s sleep and seeing the next morning’s race, Mr. Honda had a second thought: “Europe has its own long and unique history with motorcycles, whereas Japan doesn’t. Still, the fact that I saw real things on this trip will have the same effect as seeing history in the making.” With a burning determination – studying is the first and foremost priority – Mr. Honda set out on his return trip to Japan.

Mr. Honda then formed a task force to pursue TT racing and assigned Kiyoshi Kawashima to the development of a racing engine. Entrusting Mr. Fujisawa with financing of the project, Mr. Honda devoted himself to the development of a racing machine.

When Kawashima asked Mr. Honda if he was serious about competing in the TT Races, Mr. Honda replied, “We need dreams especially now as we are facing difficult times. Now is the perfect time to sow the seeds for tomorrow’s flowers.”

Around this time, motorcycle racing was becoming increasingly popular in Japan, as well. Honda competed in the Asama Highland Race*3 and the Asama Volcano Race*4 in 1955 and 1957, respectively. By taking on challenges in racing, Honda advanced and refined its technology to develop world-class, high-performance motorcycles.

- The 1st All-Japan Motorcycle Endurance Road Race

- The 2nd All-Japan Motorcycle Endurance Road Race

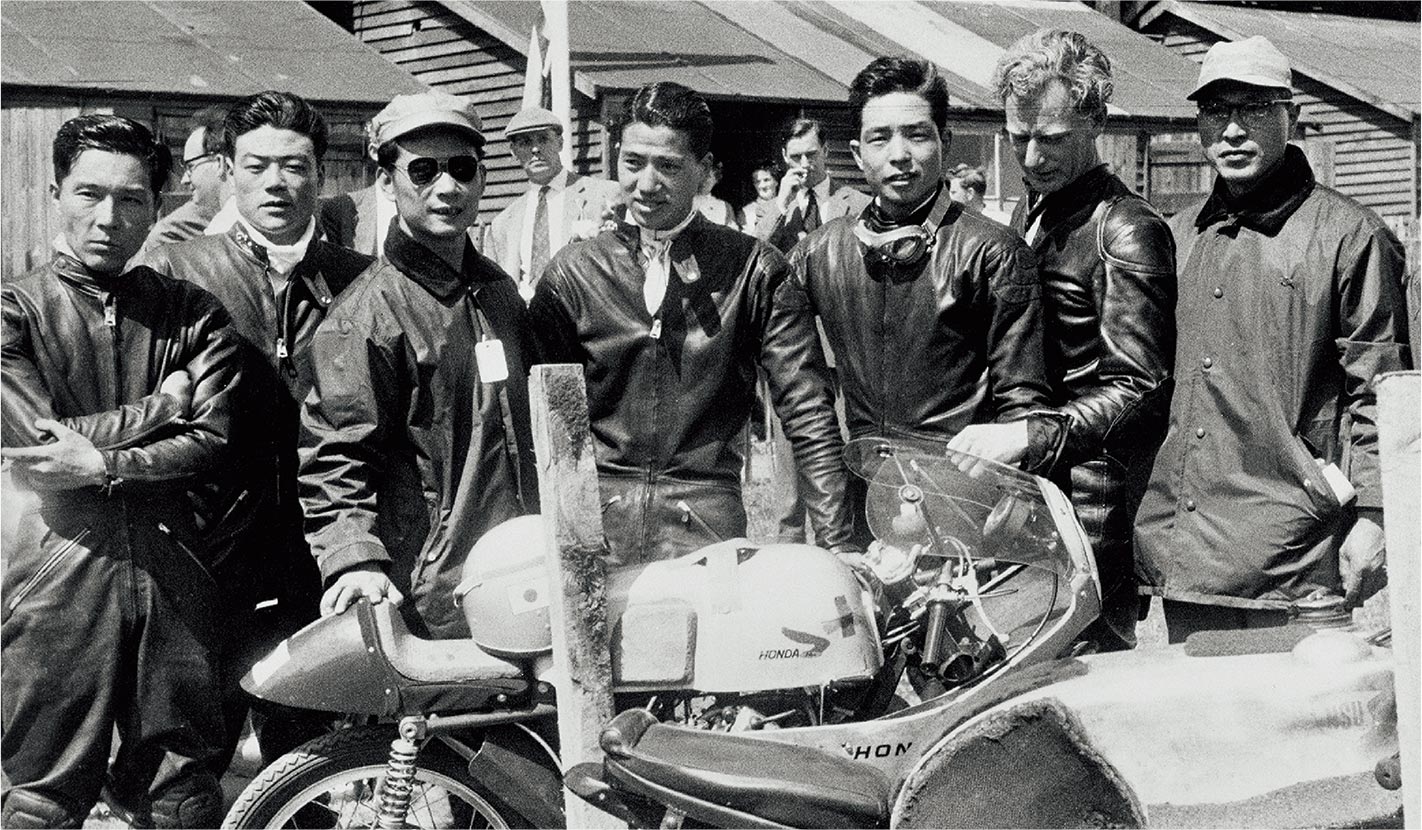

In June 1959, the Honda team made its long-awaited debut in the Isle of Man TT Races. Although the team had one American rider, this was the first time in the history of the TT Races that as many as four Japanese riders had competed in the race on Japanese-made racing machines. Despite the tougher-than-expected road surface and course conditions and tough competition against a number of world-class riders, four of the five Honda machines finished the race, and Honda won the Manufacturers’ Team Award in the 125cc class. In the following year, 1960, Honda riders occupied 6th through 10th places in the 125cc class, and 4th through 6th places in the 250cc class.

Wining the Isle of Man TT Races:

Emerging as the World’s Leading Motorcycle Manufacturer

First appearance in the Isle of Man TT Races (1959)

From left: Junzo Suzuki, Giichi Suzuki, Kiyoshi Kawashima, Naomi Taniguchi, Teisuke Tanaka, Bill Hunt, and Hisaichi Sekiguchi (chief of maintenance)

In June 1961, in its third attempt, Honda finally won the race outright and took the top five spots in both the 125cc and 250cc classes, while also setting new lap records for the TT Races. This was the moment when Honda engines were thrust into the global spotlight.

The Daily Mirror, a British national daily newspaper, wrote: “How did a Japanese manufacturer, that had only competed in the TT Races three times, achieve such an astonishing success? ... Frankly, when we disassembled and studied a Honda machine, we were shocked in amazement. It was built like a precision watch and was not at all a copy of any other machines. We realized that Honda had been creating its machines based on their original and brilliant thinking.”

At Honda, engine development was led by a team of young engineers that included Kiyoshi Kawashima and Tadashi Kume (who later become the second and third presidents of Honda). Kawashima later recalled his three years as the leader of the Honda TT race team: “I learned quite a lot from the project, and from my experience being a team leader – judgment, decisiveness and foresight – as well as how to best draw out people’s abilities and how to enable people with strong personalities to work together, and how to develop and implement both an overall strategy and detailed tactics. These skills all came in handy when I later assumed the role as the company president. Even while facing tough times, I was able to withstand any adversities and kept my challenging spirit going, by remembering my days as the TT race team leader. In that sense, too, I feel that I was privileged to be assigned to lead that project.”

What significance did competing in the Isle of Man TT Races have for Honda?

Ultimately, it served as a unique proving ground where advancement of Honda technologies was accelerated. It also infused the entire company with a sense of unity and accomplishment, as everyone shared a big dream. Moreover, from a marketing perspective, it was a great opportunity to get positive publicity globally that allowed Honda to showcase its high-performance and high-quality technology.

With an eye toward future entry into the European market, Honda leveraged this racing project as a part of the strategy to let its technological strengths and presence be known in the market. Honda’s Isle of Man TT Race victories coincided with a gradual change in the way Japanese products were viewed outside Japan, resulting in an increase in exports of a broad range of Japanese-made industrial products.

Establishment of the Honda Company Principle

In 1956, two years after the issuance of the Declaration of Entry in the Isle of Man TT Races, the Honda Company Principle was announced for the first time.

Since its founding, Honda had been driven by the passion of the founding members, facing various difficulties and pushing the limits. The two founders realized that the time had come to codify the values the company had learned as a manufacturing company whose primary focus is on monozukuri, or the art of making things.

The following statement is part of the original Company Principle which appeared, along with the Honda Management Policies, in the 23rd issue of the Honda company newsletter published in January 1956:

“Maintaining an international viewpoint, the company is dedicated to manufacturing products excellent in performance yet an inexpensive price in response to the needs of the customers”

See the world. Think from the customer’s perspective. Never compromise on product performance. Accommodate customer demand for lower prices. This statement became the original expression of the current Honda Company Principle and Management Policies, which was already shedding light on the Honda’s future beyond the half-century mark, in every aspect including the company’s viewpoint, attitude and mission.

Betting the Future of Honda on the Super Cub

In 1956, both Mr. Honda and Mr. Fujisawa took off on a trip to Europe. Honda had recently discontinued the production of the Cub F-Type as the era of auxiliary bicycle engines was beginning to come to an end.

Mr. Fujisawa had begun making plans to create the next hit Honda product and sell it both inside and outside Japan. However, he lacked a clear image of what this important new product should be. So, in the interests of market research, both Messrs. Honda and Fujisawa traveled to Europe where small-size motorbikes with pedals, so called “mopeds,” equipped with a 50cc engine, were in widespread use.

In 1958, two years after the founders’ research trip to Europe, Honda debuted the Super Cub C100 equipped with a 50cc four-stroke engine, an automatic centrifugal clutch and a three-speed transmission, featuring the smallest engine size among Honda motorcycle products.

The convenience and satisfaction of the rider was thoroughly thought through in the design of the Super Cub: riding stability, ability to handle rough road surfaces, seat height for easy straddling and comfortable footing, as well as achieving both high power output and low fuel consumption.

Honda designed this new 50cc model while envisioning a broad range of target users, including those who use a bike for commuting to work and school, for commercial purposes, and for recreational purposes. Moreover, in order to break out of the existing motorcycle market and achieve greater sales volume, Honda took a groundbreaking approach to its monozukuri, keeping female consumers in mind.

At the start of the project, Mr. Fujisawa requested, “Make a motorcycle that your wife will give an OK,” indicating how conscious Honda was of the viewpoint of female consumers in the development of the Super Cub.

The concept of featuring a motorcycle body with “no visible guts (no exposed engine parts)” was set early on in the product planning, in the hope of eliminating the roguish image associated with motorcycles at the time and creating a positive and friendly image that would encourage women to consider riding it themselves. Moreover, giving various considerations to the ease of riding while wearing a skirt, the styling design featured an S-shaped frame layout for easy straddling, as well as a windbreaking leg shield, a front fender and side cover, which conveyed the image of soft surfaces and lines achievable only through resin molding parts. These features characterized the unique styling of the Super Cub and the resin molding technology Honda developed, originally for the Juno, contributed to the distinctive design of Super Cub.

While presenting the prototype, Mr. Honda asked Mr. Fujisawa: “How many do you think we can sell?”

Mr. Fujisawa replied: “Maybe around 30,000 units.”

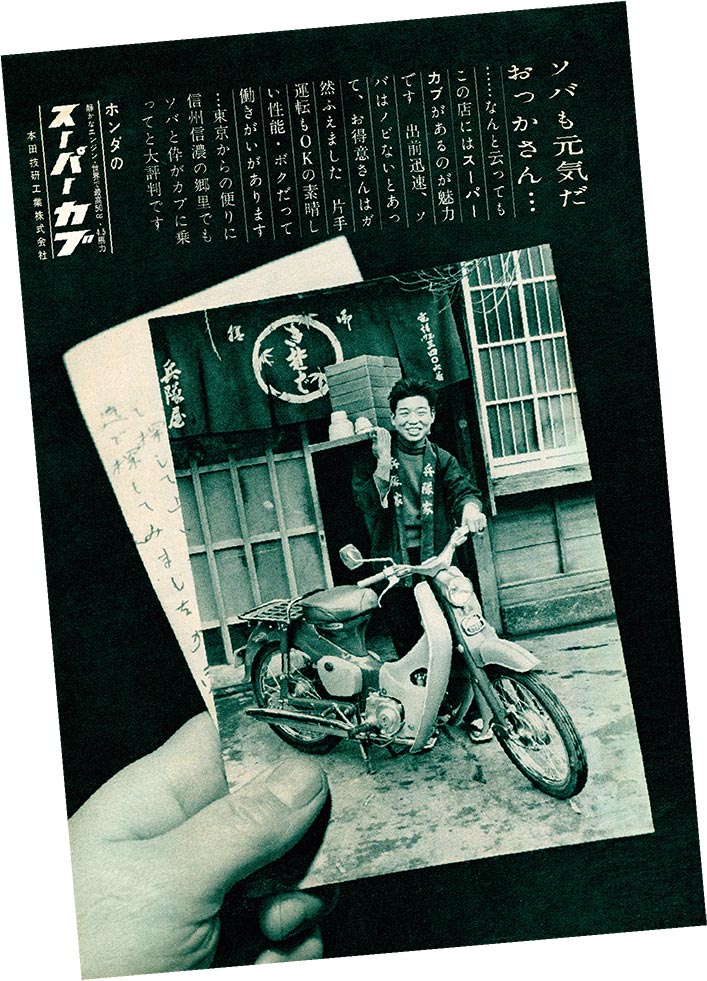

The first ad in a national newspaper

The first ad in a national newspaper “The Soba is Good, Too, Ma!” version

Everyone there interpreted that as “30,000 units a year” and accepted Mr. Fujisawa’s sale forecast. However, Mr. Fujisawa actually meant “30,000 units per month.”

This sales forecast was a reflection of Mr. Fujisawa’s bold management strategy: to create a high-performance product that overwhelms the competition by applying Honda technological strengths, to sell such a product at a low price without reflecting the high cost of development in the selling price, and then to recoup the investment by setting and realizing out-of-the-ordinary sales volume. Furthermore, Mr. Fujisawa was already envisioning the mass production of this model at a dedicated plant. Honda was betting the future of the company on this new product.

In July 1958, as soon as the Super Cub C100 went on sale, it created a huge sensation.

To this day, while inheriting the basic Super Cub package intact, Super Cub series models continue to be advanced to better accommodate customer needs in each region and currently being produced in a number of countries around the world including Japan. More than 65 years after its debut, the Super Cub series is still enjoyed by people all around the world as an essential product for their mobility and daily lives.

The passion of Honda to help people with its own technology, which is still at the core of the Honda 2030 Vision of serving people worldwide with the “joy of expanding their life’s potential,” is what resulted in this long-selling product of Honda: the Super Cub.

Super Cub C100 (1958)