Odyssey / 1994

Developing a Car with a Roomy Interior

Kunimichi Odagaki, then a chief engineer (CE) at the R&D Center was stationed at Sayama Factory to assist the launch of the 1991 Legend where he received a phone call in August 1990. The center wished to develop a roomy new car for the U.S. market. Specifically, they told him to establish a new plant in the U.S. to develop a new large-size minivan; one powered by the V6 engine from the upscale Acura Legend. The plan reflected a strong desire by Koichi Amemiya, president of American Honda, to set a new standard for that growing segment of the American market.

The Odyssey S 4WD model (with power sunroof) released in October 1994

Odagaki went to work immediately, assembling a team of twenty to develop the project. As LPL of the development project, Odagaki flew to the U.S. in September 1990 with five or six of his team members. For the next month, they conducted an intensive review of existing minivan competitors in the U.S.

"It was a time in which American consumers were changing their minds," Odagaki recalled. "Rather than wanting more luxurious cars, they began looking for models that could more easily accommodate specific uses. We couldn’t have agreed more with that idea, and were strongly convinced that Honda had to develop its own minivan."

The minivans that were sold in the U.S. during that period generally cost around $20,000, but Honda’s proposed model was to be considerably more expensive than that. Including the costs of building a new plant and installing the Legend V6 engine, the anticipated retail price was as much as $30,000. Therefore, the four-cylinder power plant from the Accord was considered as a more affordable alternative. However, just as the team had shifted into top gear, the management canceled the minivan development project.

Odagaki called the representatives of automotive development (RAD) at the head office, pleading with him to reconsider. "I understand this is an order," he said, "but I don’t think we should cancel the project." He was determined to create a car that would answer the demand for a high-quality, supremely functional minivan for the American market. However, even after 40 minutes on the telephone, Odagaki had not succeeded in convincing the RAD.

Odagaki’s team members felt strongly that the project should be continued. For one thing, they had seen with their own eyes the explosive growth of this new market segment. Moreover, they believed that Japan would be the next step in the growth of this new culture.

The team quietly began its own "underground" development effort at the end of that year, working outside the realm of official duty. In the face of numerous difficulties, though, their only hope was the fact that the company president, executive director in charge of product, and the top management at the R&D Center had tacitly approved the continuation of this project.

The team members visited recreational sites and sporting sites across a considerable range of market territory, interviewing minivan owners and observing how the vehicles were used.

"We wanted to know precisely what the customer wanted," said Odagaki. "Only after understanding their needs could we create a value that no other car provided; the kind of value that would win the customer’s heart. We took it upon ourselves to answer that challenge."

Target Concept: A Personal Jet

The first generation Odyssey minivan’s target concept was that of a "personal jet (airplane)," and this theme was reflected in the vehicle’s "PJ" development code name. However, despite their best efforts, the team was at first unable to come up with an appealing design. Odagaki, by then quite frustrated, asked the designers why it was taking so long.

The designers countered with a serious argument about the difficulty of combining function and aesthetics. "The image of a car with three rows of seats is simply too homespun," they said. "It’s impossible to accommodate that kind of structure in a stylish design."

Odagaki could certainly see their point, but his view of the question was decidedly more objective. Therefore, he came up with the idea of a third row of seats that could be folded into a compartment beneath the floor. When the seats were up, the compartment could be used for cargo storage. When the seats were stowed, the center of gravity would become lower, thereby enhancing the vehicle’s performance. Therefore, the key point of discussion became a center aisle that would allow passengers to walk through to the third row of seats.

"The walk-through aisle was the thing that really impressed me with many minivans in the U.S.," stated Odagaki. "When the car is driving through beautiful scenery, passengers could easily change seats to get a better view. It was like taking a bullet train - another means of rapid transportation - since the passengers could freely move to other empty seats. Therefore, we wanted to create a "family bullet train." It was a benefit that no other car could provide, and we were determined to develop such a car."

A Styrofoam mock-up was created in order to determine the interior height required for such a feature, and the team discovered that a minimum height of 1.2 meters was required for the passengers to comfortably move about inside the cabin. Moreover, the lower the floor was above the ground, the easier it would be for passengers to enter and exit the vehicle. But there was an added benefit here, in that it would effectively enhance productivity on the assembly line at the factory. Based on these findings, the car’s overall dimensions were simulated. After that, the problem was to find a plant that could produce such a car.

A Decision by Sayama Plant

Odagaki faxed a memo to Suzuka Factory, Saitama Factory’s Sayama Plant, and Honda of America Manufacturing (HAM). "This plan is not an official project," stated the memo. "However, we believe it’s a car that Honda should develop. Unfortunately, our study has found that the construction of a new plant would increase the required investment, making the project impractical in terms of costs. Therefore, we have designed a feasible package that maintains the necessary interior space for passengers, yet that can be manufactured through minimal changes to an existing production line. Please consider the possibility of manufacturing the car at your Factory." Subsequently, HAM and the Sayama Plant replied that they might be able to accommodate the request.

"The collapse of Japan’s bubble economy had reduced the overall market for sedans," recalled Hiroshi Sekine, who was EPL for the Odyssey introduction project at Sayama Plant. "By contrast, the RV (recreational vehicle) market was growing. RV was a category in which Honda didn’t have an entry. At the same time, we were aware of the obvious lack of capacity that Saitama Factory would face. It was anticipated that Sayama Plant’s Line Number 1 would become idle within two or three years."

Hiroyuki Shimojima, then managing director and Saitama Factory’s general manager, had decided that the factory should introduce a new car in order to revitalize the plant and its employees.

"We on the manufacturing side had to do several things first," Sekine said. "We had to maximize our factory’s unique characteristics as a passenger-car plant, achieve stable quality, minimize the investment, and employ existing equipment effectively. However, we couldn’t meet those requirements using the design provided by the R&D Center. So, we worked with their staff in order to change the car."

The body of the Odyssey minivan was larger and heavier than existing models produced by the factory. Therefore, the first step was to conduct a thorough procedural analysis and identify what needed to be changed.

Each of those items was then verified by Sekine, who walked through the line and checked every point. This resulted in a substantially reduced investment required to build the vehicle.

Following the preparation of his investment forecast, Sekine visited the Production Planning Office and presented it to the Investment Evaluation Committee. There, he was given a discouraging comment by the head of the Planning Office, who said, "Sekine, why don’t you propose canceling the development? I’m telling you, this car will not sell." However, after the committee’s evaluation an approval was given by Senior Managing Director Nobuyuki Otsuka.

"Nobody had given me an answer as to whether the car was to be manufactured at Sayama Plant or at HAM," said Sekine, recalling his conversation with Otsuka. "So, in order for us to minimize any damage suffered in the event that HAM was chosen, I will check the progress every two months and identify the minimum investment requirements. Then I’d come back to him with each investment plan and obtain his approval."

"What a dirty tactic," replied Otsuka, rather jokingly. "If the investment is too big, I can tell you to reduce it. But if you bring me an investment plan for a small amount every two months, how can I say no?" Otsuka also gave Sekine a detailed evaluation of the plan.

It was Sekine’s goal to bring the Odyssey project to Sayama Plant, no matter what the difficulties might be.

The intra-company competition between Sayama and HAM continued until the final decision had at last been made. The competition was so fierce, in fact, that if Sayama Plant had refused the project it would have been taken to the U.S. immediately.

Another factor surrounding the first generation Odyssey project involved the collapse of Japan’s bubble economy, rising yen, and recessionary trend - all of which made it difficult to discern the true state of the Japanese business environment. Further complicating matters, the minivan would face 25-percent tariffs if it were imported to the U.S.

One Car, Two Visions: Sales Versus Engineering

The plan for facilities investments needed in preparation for Odyssey production was well under way at the Sayama Plant, but the Sales Division in Japan remained skeptical about the new car and its chances for success in the market. At the time 70 percent of "one-box" cars were powered by diesel motors. However, the Domestic Sales wanted a one-box car with a sliding door, just like those of other manufacturers. In fact, more and more Honda owners were switching to other brands in order to get them.

"Diesel engines may have been acceptable in the past when the safety or the environment was not so important issue," said Odagaki. "But the Odyssey was to reflect the way family cars would look in the future. I insisted on this, perhaps with a certain amount of self-praise. I said we could change the world by introducing this car, and I maintained that we should release it as soon as possible. I tried my best to convince them, saying we could build it at our existing plant using the existing facilities and Accord parts, and that the required investment and development time could be kept to the absolute minimum."

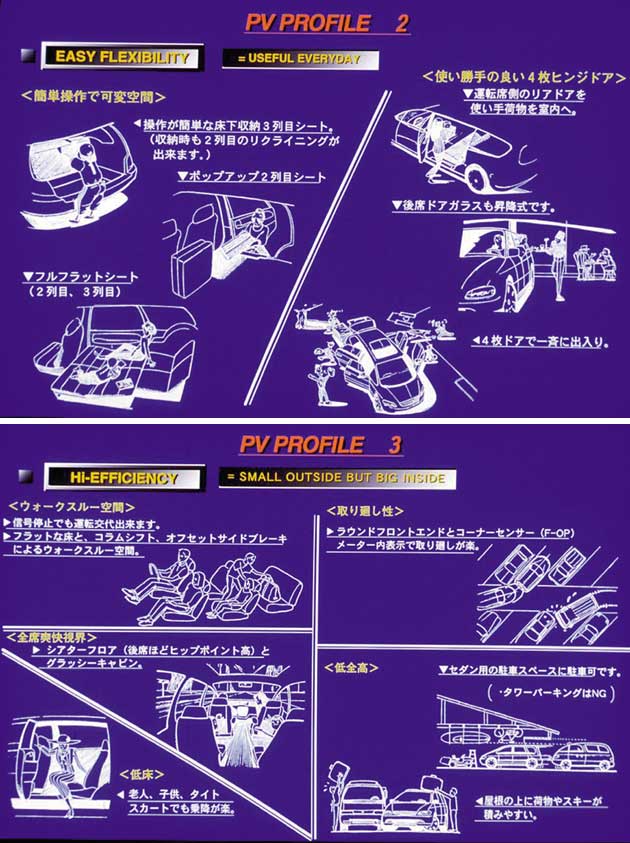

Sales management was not to be won over so quickly, but Odagaki and his team members simply would not give up. Instead, they focused on the challenge of making a more effective presentation the next time around. After careful consideration, they decided to use illustrations to explain concepts that mere words would make difficult to understand. Illustrations, for example, could show how easily the seats could be stored and lifted, and which functions were used when and in what way.

Detailed, high-impact illustrations were used in the presentation in order to win as much support as possible.

The team employed a one-quarter scale model and full-size Styrofoam package model in its presentation at the Corporate Strategic Meeting and Special Reporting Session. It made no difference to them that the full-scale mock-up consumed a significant amount of space within the conference area, since they wanted the decision-makers to actually get into it. In fact, they knew that was essential to gaining the support they needed.

Also explained at these meetings were sample use patterns based on various applications. Among the several simulations the team presented was one describing the vehicle’s benefit to golfing enthusiasts, a point well taken by the sales managers. The team explained: "This one can carry four golf bags without having to stack them on top of one another. Furthermore, people won’t mistake your car parked at the clubhouse entrance for some generic shuttle bus hired by the club."

Nobuhiko Kawamoto, Honda’s president, in summarizing the overall response immediately expressed his support for the Odyssey project. However, North American Sales did not show much interest in the new minivan, which was less powerful and smaller in size than its U.S. counterparts. The upper-level representatives from Japanese Sales showed their reluctance due to the car’s divergence from traditional one-box models.

The Concept that Overcame the Adversity

The team also faced many difficulties at the R&D Center. For example, while Odagaki was away on a business trip, he was informed that some team members had been told to work on urgent drawings for another project, so upon his return he had to fight hard with the manager of that project in order to get his men back. Since what they were developing was not an approved product model, there were many hurdles to clear.

Fortunately, there were supporters as well, including Michiyoshi Hagino, senior managing director of the R&D Center. "First let’s create a running prototype," he said. "Then they’ll understand the benefits of this car. But for the time being, the team members must continue to work on the project unofficially."

Accordingly, Odagaki asked Takefumi Hiramatsu, managing director in charge of development operations, to commit twenty employees to prototype development, on the condition that no new processes would be added. His request was approved on April 16, 1991.

The prototype created by the twenty-member team had a graceful bodyline embellished by motorcycle headlights and the Acty’s tail lamps. The steering wheel was positioned on the right, because the company’s prime focus at the time was to improve its automobile sales in Japan. Thus, the team began its effort to convince the Sales Division using this running prototype.

"If we try," they argued, "we can develop a car that drives like a sedan but offers much more interior space. But we really should introduce the U.S. minivan culture to Japan. This car will become a powerful weapon in increasing our sales domestically."

Gradually, support for the Odyssey increased. However, Domestic Sales remained hesitant about giving its endorsement. The team decided to bring the prototype to the U.S. and sell it to American Honda. The initial order Odagaki had been given in August, 1991 was to develop a new car: a minivan for the American market. However, even though the prototype was smaller than had originally been envisioned, he was confident that it would be accepted in the U.S.

A test drive was held in Los Angeles the evening of January 10, 1992. Amemiya, who came to the test drive, saw the steering wheel on the right side and immediately said, "This team can’t be serious. They’re thinking about the Japanese market."

Still, the team managed to convince Amemiya to drive the car. Odagaki, sitting next to him, described the hardships that he and his team had thus far endured.

"The project would have been scrapped by then if we hadn’t built the prototype with a right-hand design," Odagaki told Amemiya. "Regardless of the steering wheel’s location, I honestly believe this car will be a strong asset for your operations in the U.S. We really need your support."

Some time after the development team had returned from the U.S., they received good news. American Honda had offered a plan to sell 5,000 units per month. Still, a "go" sign by Japanese Sales had yet to be obtained. However, the endorsement by American Honda, which was responsible for selling large quantities of product, ensured that the Odyssey project would finally move forward.

"I really didn’t think we could develop a great product if everything went too smoothly," Odagaki said of that period. "In our case, the team members had a clear idea as to what we should create. But we also knew how to fight. Because of that vision, and perhaps helped along by the current trend, we were able to overcome adversity."

A Simultaneous Launching through Three Sales Channels and the Challenge of Increased Production

The Odyssey, having overcome numerous obstacles, was finally launched on October 20, 1994. At the official ceremony, Odagaki described the vehicle’s development background. When he came to the passage, "...it was because the team members...," he could no longer hold back his tears.

The Odyssey’s line-off ceremony held on October 3, 1994, at Saitama Factory’s Sayama Plant, was attended by representatives from business partners and dealers, along with numerous associates. There was an atmosphere of celebration surrounding the launch of Honda’s new minivan.

The Odyssey became the first Honda model in Company history to be released simultaneously through all three distribution channels (Primo, Clio, Verno). Because it was a utility vehicle - albeit one in a completely new category - the company decided to market the Odyssey through different channels under the same name to drive market penetration.

Contrary to the company’s initial assessment, the Odyssey was met with an enthusiastic reception among journalists and customers. In fact, the car received two of the most coveted industry awards in its first year, the Japan Car of the Year Award (Special Category) and the RJC New Car of the Year Award. By the end of September 1997, 36 months after its release, the Odyssey had sold more than 300,000 units, breaking the Civic’s record to become Honda’s fastest-selling new car.

"When we first started developing the Odyssey," Sekine recalled, "there was criticism that we could only copy models from other manufacturers. But I believe the market accepted our development concept, which was essentially based on the user’s point of view. So, this project showed us how important it was to approach every design from the customer’s perspective."

The Odyssey’s initial production volume was 341 units per day, but soon after its launch, sales had not picked up, and the line’s rate of output was still low. Therefore, Sekine postponed further investment in improvements, promising that the company would spend the money when it was warranted by market conditions and the required volume. He also proposed a cut in the production line’s capacity from 1,100 units down to 1,050 per day.

Eventually, sales began to grow, resulting in several production-volume increases. As promised, Sekine implemented the investment for improvements. However, the factory’s young employees were the motivating force behind such expenditures, in that they identified each area of improvement and tackled problems based on the Honda’s principle of "focusing on real-world, on-site operations while facing up to the challenges inherent in reaching their goal." Their effort brought about a dramatic increase in production volume, yet with maximized use of a relatively minimal investment.

"When we reviewed the process of increasing production volume," Sekine said, "we found many areas in need of improvement. These problems were solved by the employees themselves. The process of voluntary reform, in which the improvement of each process was left to those in charge of the process, caused each and every employee to cultivate a critical mind and share in that sense of achievement."

Beginning a New Odyssey in North America

The line-off ceremony for the second generation Odyssey was held on September 30, 1998, at Honda of Canada Manufacturing (HCM), the continent’s newly constructed second production line. Thus, the car created in response to America’s love of the minivan concept was a reality. It had taken Odagaki and his development team eight long years - from a vehicle envisioned for the U.S. market to one produced for Japanese roads, then back to the original idea - and countless man-hours to see it through.

"When development of the Odyssey began," Odagaki recalled, "Mr. Amemiya had a strong conviction that sedans were losing their popularity in the U.S. and that Honda could be driven out of the market if it didn’t develop its own minivans and SUVs (sport utility vehicles). This was despite the strong position Honda was then enjoying in the U.S. with extremely popular models such as the Civic and Accord. In the U.S., several minivan projects had been started and canceled. This time - one of four, in all - we were finally able to create the minivan we really wanted."

The development of the Odyssey, a car that satisfied the creative lifestyle of today’s consumer, marked the birth of a completely new passenger-car category. Naturally, other manufacturers soon released their versions of the Odyssey, proving that it was truly the car that consumers desired. Said Odagaki, "Nothing could be more satisfying to an industrial engineer than to see that the product he has created can bring joy to so many people," says Odagaki.