Road Pal / 1976

The Four-Man Development Team

The motorcycle market encountered a critical deadlock in the early 1970s. The popularity of light, high-economy cars was growing, and the activities of motorcycle gangs was hurting the motorcycle's once-sterling image as a fun, convenient means oftransportation. Moreover, the "three don'ts" movement that had proliferated among Japanese high-school students was a negative influence. Consequently, sales of motorcycles went into a sharp decline.

Even the venerated Super Cub, the star of a worldwide motorcycle boom, found itself in a slump some fifteen years after its release. As original owners grew older, and with the bike failing to attract members of the younger generation, the Super Cub was unable to maintain or increase its market.

The people at Honda were deeply concerned about the situation: If no action was taken, the motorcycle market would shrink even more, causing serious damage to the company. To survive in the market, they were forced to develop a product that could foster new demand by replacing the Super Cub as Honda's mainstay model.

However, something would indeed be done, and soon. Therefore, it was Isamu Goto - who was involved in the development of automatic transmissions at the Wako R&D Center - who received a sudden transfer from his work in cars to the company's Motorcycle Division.

"I can't even ride a motorcycle," said Goto reluctantly to Takashi Kume, the managing director from Honda Motor, upon being told the news.

He was surprised by Kume, who in his reply said, "But you see, that‘s why you're so right for this job."

Goto quickly learned that what Kume wanted was to see the motorcycle market through the eyes of someone who was not a motorcycle enthusiast - someone who did not know anything about motorcycles - in order to gain a foothold in the development of bikes that would be welcomed by the general public as well as enthusiasts. Therefore, Goto moved to the Asaka R&D Center, which had recently been established as a separate R&D facility for motorcycles.

Goto, however doubtful he may have been, was to begin with the strong support of three colleagues. All were brilliant engineers, being experts in the frame construction, engine design, and styling. Soon, a development team was formed, and the foursome began working on a new concept.

The Lesson from Chaly

Mikihiro Koyama, one of the team members, was a veteran in the development of small family bikes like the second-generation Cub and Dax. He had also acted as manager of development for the Chaly, launched in 1972. Following the Super Cub, Honda had made several attempts to develop new markets with new models, and the Chaly was one such trial product. However, prior to the development of the Chaly, Koyama and his team had found that although 20 percent of women were licensed to ride motorcycles, fewer than 10 percent of them actually did so. Their goal was to attract these users.

Koyama and his associates invited female employees to take test rides on the Cub to gather research data, and found that most of the employees were not pleased with it. Major complaints included, "The stand is too difficult to extend," "its difficult to kick-start it," and "I can't ride it while wearing a skirt."

Reflecting these findings, several plans were developed to ensure user-friendly operation and a sense of safety. To satisfy such requirements, the weight of the bike had to be reduced. However, there was no time to pursue further weight reductions, because the key development objective was to release the new model as soon as possible, using the Cub engine to save time. Said Koyama of the Chaly's release, "We were not satisfied, but nevertheless we managed to convince ourselves that it was a step-through version of the Dax."

A product of speedy development, taking just six months from planning to launch, the Chaly achieved its original objective of winning female users (the number of women owners was significantly larger than with other models), which had heretofore been considered difficult to achieve. Still, there were many problems, including the kick starter and shift pedal.

"In developing the Chaly," Koyama said, "we discovered the depth of our market of female users. Because of our blind faith in the almighty Cub, we had neglected a sincere effort to developing this market," says Koyama.

Market Research - Tape Recorder in Hand

A plan was implemented in 1972 to revive the motorcycle market by creating new demand. Therefore, Goto and the other three members of the development team started by conducting research - personally and on foot - and gathering a significant amount of thorough market data.

The team wanted answers to numerous questions, one of which was why women did not ride bikes in the city. The development team traveled the country in search of an answer. They went to bike parking lots in front of train stations located in hilly areas and interviewed women, tape recorders in hand.

A majority of women, when asked if it was easier to ride a bike on an uphill road, pointed out the negative aspects of motorcycles, such as being "dangerous," "noisy," and "prone to accidents."

The team then realized they had to design an innovative motorcycle that would dispel the image of the conventional motorcycle. Ultimately, they locked themselves in a room and drew countless layout sketches. Then they taped them to the walls and critiqued them through endless hours of discussion.

They also examined best seller products from completely different categories - including cameras, household appliances, and other things - in order to study the mechanisms of product development. They even studied the workings of human desire.

The New Cycle (NC) Plan

A new planning concept was developed in the summer of 1973, based on the findings of the "R" plan (market-research stage), which had earlier been implemented. Called the New Cycle Plan (NC), it was defined by four key concepts:

NC-0: Powered cycles (later embodied in the People)

NC-1: New motorcycles, encompassing bicycles (pedal scooters and mopeds)

NC-2: New motorcycles replacing the Cub (scooters, later embodied in the Tact)

NC-3: Three-wheel (four-wheel) bikes with the image of a passenger car (Threeter)

Of the four, the NC-1 concept based on the theme of a motorcycle having the image of a bicycle, was chosen as the first project for breakthrough, since the concept was practical and the materials were familiar.

Koyama recalled the yearlong product research, in which the team was given complete freedom, assessing their accomplishments:

"In the past, product development was done entirely at the R&D centers. Often, drawings would be issued without reflecting what the customer really wanted, in this sense, that particular research proved quite effective, since we were able to do everything we wanted in the planning stage before the D-development began."

Believing it would not be sufficient to create simple variations of the Cub, such as those explored in the Nobio and Chaly, the team continued searching for more ideal forms, including those that were not feasible. This, they felt, would lead them to a simpler, lighter motorcycle that more closely resembled a bicycle.

"It doesn't matter whether it's feasible," Kume said encouragingly. "We'll think of the technology to achieve it later."

The NC plan produced a compilation of ideal requirements that could be achieved with a fair amount of effort. The NC-1 project was the First such concept to get the green light.

Sparing No Discussion to Achieve the Goal

The concept for development required an external design that did not emphasize the engine. Accordingly, a bicycle-like silhouette was designed with the engine placed amid-ships. The weight was to be held to 25 kg so that a woman could lift the bike. The target price was set at 50,000 yen, or equivalent to the price of two bicycles. To achieve the target weight and torque, a simple, 2-stroke engine was adopted as a compromise. However, these decisions were made without first consulting the Old Man (Soichiro Honda), who loathed 2-cycle engines.

The method used to start the bike was going to be a problem. They knew women would dislike having to use a kick-starter, but the use of a cell motor, the preferred choice, was obviously impossible due to its high cost. They tested a variety of methods, such as an applied system based on compressed air, a mechanism utilizing the weight shift that occurs as the rider is seated, and the gunpowder cartridge system. Initially, they adopted the "woodpecker method," in which a spring is wound by the reverse rotation of the rear wheel and its unwinding force is used to start the engine. The name came from the starting action of moving the bike backward, which resembles the movement of a woodpecker.

However, this method was never adopted, because the spring failed to wind at the evaluation meeting (held in January 1974), where the snow-covered road caused the wheel to slip. In the end, it was decided to use the pedal to wind the spring.

A test ride was held in April 1974, at which fifteen women, all wives of R&D center employees, were invited to try out the prototype bike. Although some unexpected mishaps occurred, with one bike crashing into a fence after the throttle was opened too wide, the overall scores were satisfactory.

Many of the riders were excited, offering such comments as "It‘s fun" and "This bike is great!"

Goto and his team had at last found the boost of confidence they needed. "Controlling a motorcycle with the hands can make a woman feel excited, just as it does a man," the team members reasoned. "The difference is that women had no opportunity to feel that excitement."

The S•E•D flow began quickly, according to Honda's new system of development. For the first time a development project was started with the Sales (S), Production Engineering (B), and Development (D) departments contributing their full effort.

"There were problems in the beginning, since it took extra time to explain the data and show actual proof to convince the evaluators," said Koyama of the new system.

The Sales Department worked energetically from the initial stages, building the product's image and implementing a promotional campaign. To maximize the effects of promotion, they decided to run a daring commercial for a motorcycle, featuring the world-famous Italian actress Sophia Loren.

At the start of D-development, the sales target was set at 360,000 units per year (120,000 units in the first year) which according to Koyama was "simply not a number you can achieve halfheartedly." The cost was also tight, because a price ranging from 50,000 to 355,000 yen had to yield a 10-percent profit. To satisfy these requirements, the design for mass production was modified four times,

To achieve their overall objective, individual groups in charge of the engine, frame, and other parts were asked to set targets for each part. They agreed that the green light would not be given until each part had met its target.

"We camped several days at a hotel in Nerima with the persons in charge of materials, plant, and design, in order to discuss things to our mutual satisfaction," says Koyama.

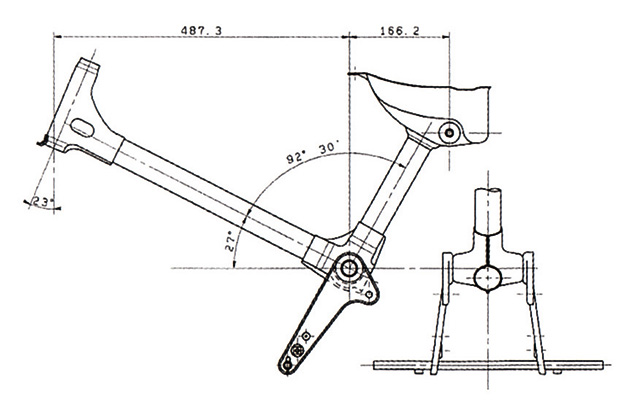

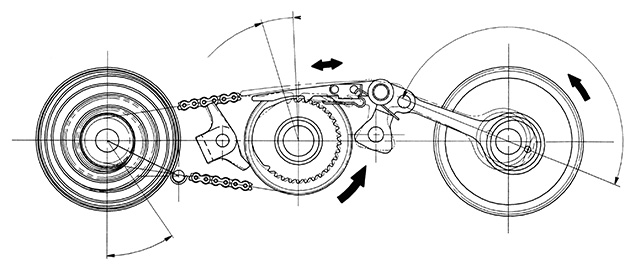

Achieving the goal would be impossible unless the number of parts was reduced to a minimum and total weight was kept at around 60 percent of the Cub. Therefore, having no other choice, they sought ways to minimize the number of parts. One effective measure was the adoption of a unit swing system, which provided a simple means of integrating the engine, rear fork, and wheel. The frame was also simplified as much as possible through a design rising the minimum allowable componentry.

The frame design has the look of bicycle layout.

Sketches used in the development stage. The sketch used at the start of development (green frame) evolved into the final sketch (yellow frame) employing the frame concept.

The first mockup model to adopt the frame concept

Drawing of automatic winding mechanism

Even all these measures, however, could not keep costs down. Days of agonizing effort ensued. It was then that EG's Production Engineering Department proposed an "in-furnace brazing system." The idea was to place the frame components on a conveyer and run them through a reduction furnace heated to several hundred degrees. The components would come out of the furnace completely brazed and free of rust, ready for immediate painting. The use of this system thus provided significant savings in welding costs.

This new method was also applied to the integrated fuel/oil tank positioned under the carrier. Several other radical concepts were adopted to ensure the rationalization of design, including the layout of electrical parts, which were housed under the seat and enclosed in polystyrene foam.

The Market that Never Fades

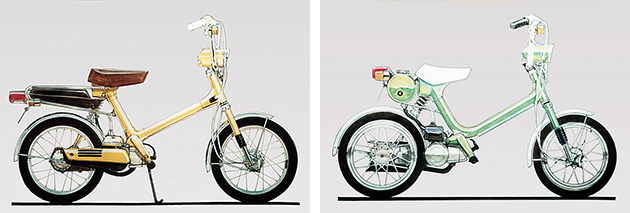

In February 1976, the Honda Road Pal was released as a completely new vehicle, being neither a motorcycle nor bicycle. Launched with the now-legendary commercial that gave rise to the fad phrase, "La-tta-rta," the Road Pal captivated consumers with its affordable price, convenience, and simplicity of use. In fact, the model was a tremendous seller, appealing mostly to first-time buyers (68.4% of purchasers), women (62.2%), and users in their 30s to 40s (61%). Undoubtedly, a significant portion of the Road Pal's success came from the commercial featuring Sophia Loren, which became the talk of the whole nation. Improvements were made to reflect findings from customer surveys. For instance, the following year saw the new Road Pal L offering an automatic winding starter system based on a suggestion by Soichiro Honda. Yet, another modified version was released in 1979, delivering higher running performance using a two-speed, planetary gear automatic transmission.

The Road Pal created a new market for motorcycles.

The Japanese demand for motorcycles grew dramatically thanks to the Road Pal, which had not only achieved a commercial success with yearly sales of more than 300,000 units but also cultivated a new market for motorcycles among women. In the Road I'al's first year, the total of motorcycle units sold increased to 1.3 million from 1.13 million the previous year, climbing to 1.62 million the following year.

The explosive growth of the domestic motorcycle market was a clear reflection of the high marks the Road Pal commanded thanks to its affordable pricing, lightweight body and superb dynamic performance. As a product that had successfully tapped the potential needs of the market, the Road Pal became a popular mode of transportation in cities and towns throughout the country.

The Road Pal's success, however, also triggered the release of family-oriented bikes by other manufacturers. Soon stylish new step-through models had become popular, threatening the Road Pal's reputation for fun, utilitarian functionality.

Production of the Road Pal was discontinued in 1983, having succeeded in the critical mission of popularizing motorcycles among ordinary family users. Without the Road Pal, the family bike boom of l 976 and the scooter boom of the 1980s would never have occurred.

"No one really pictured women on motorcycles in those days, but it is common today," said Goto, team leader of the Road Pal development project. The Road Pal was born because we had broken from this conventional thinking."

‘‘I believe the market never fades away completely. You can always find a market, if you earnestly pursue the needs of the times. That is why we have to keep creating innovative products that appeal to new and different markets."