The Hondamatic Transmission / 1968

The Army of Patents: A Barrier to the Popularization of AT Cars

The emergence of the automatic transmission (AT) was a motivating factor in the expansion of America’s car culture during the 1960s. Since it relieved the driver of the inconvenience of operating three pedals with two feet, just about anyone could drive a car with ease. Thanks to this new technology and an ever-growing network of roads, the automobile rocketed to new heights of popularity.

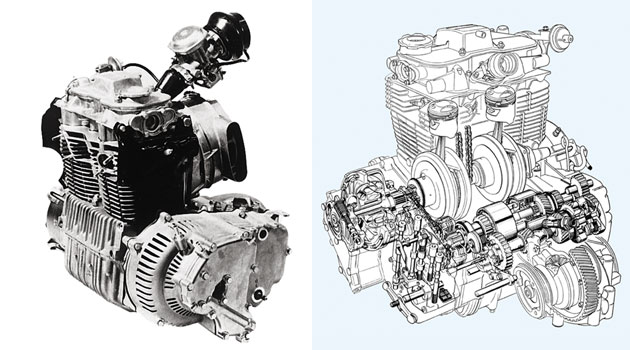

The transmission and engine of the N360AT, the first mini car equipped with a fully automatic transmission

Major luxury brands such as Lincoln, Cadillac, and Chrysler had moved to automatic transmissions by the late 1960s, and even the midprice models from Chevrolet and Ford were increasingly equipped with ATs. In fact, the penetration of AT cars approached the 80 percent mark.

The scene was completely different in Japan, however, where the automobile was just beginning to evolve as a part of daily life. In fact, the penetration of AT cars was still less than 10 percent. Automobiles were still quite expensive, and only a limited number of models adopted the AT system, since it tended to push prices even higher.

The relatively small displacements of domestic Japanese models also helped prevent manufacturers from developing AT products. In any car, a portion of the energy generated by the engine is lost as the drive force is transmitted to the wheels. The earlier automatic transmissions had not been very efficient, resulting in considerable losses of energy. For that reason it was considered difficult, if not impossible, to achieve sufficient dynamic performance from an engine of less than 1500 cc. Thus, while the larger, higher-displacement American models could certainly accommodate automatic transmissions, they simply weren’t practical for use in compact automobiles and mini cars. Accordingly, the typical Japanese consumer perceived the AT car as being "expensive and something that doesn’t drive well."

Honda had only begun making automobiles during this period, so naturally there was no AT product in the pipeline. Still endeavoring to get on-track with the car business, the company didn’t have the spare resources it could divert to the development of AT models. Moreover, there was no reason to introduce AT systems. After all, Honda didn’t yet offer a passenger car model.

The tide had turned from manual transmissions to automatics in the U.S., however, so inevitably the trend would be reflected across the Pacific. Still, any car company that decided to develop an AT model would invariably hit the same wall. As was to be expected, patents were pending or in place for just about every single aspect of AT technology.

Moreover, the majority of those patents, estimated at between 40,000 and 50,000, were in the possession of the U.S. firm Borg Warner (BW). Accordingly, Japanese automobile manufacturers were soon forced to enter into partnership agreements with BW or set up joint ventures in order to avoid the liabilities of patent infringements.

Interest in AT technology was also growing at Honda, where development of the N360 mini car was under way.

We Must Build this Dream by Ourselves

It was late in 1964. Torao Hattori, who was developing the CVT for the T360 mini truck, was in the hospital after falling ill due to stress. Development had not been moving as he had expected, which brought on an anxiety attack.

Hattori had a visitor at the hospital one day. It was Hideo Sugiura, the general manager of Honda R&D. Greetings were exchanged, after which an anxious Sugiura began to speak:

"We want to develop an automatic transmission for use in an automobile," he said, "and we want you to be in charge of it." Such unlikely words, coming from a colleague paying a get-well visit, were as much a surprise for their power of encouragement, and Hattori felt his spirits lift considerably. Hattori had designed semi-automatic transmissions for Mikasa when he was with the Yokohama-based Okamura Seisakusho. Since joining Honda he had been involved in the development of Patalini-type continuously variable transmissions for the Juno M80 and M85 series. However, his original intent in joining Honda was to design automatic transmissions for cars.

Hattori was excited about the prospect of realizing a dream, but he was also thankful that Sugiura made a trip to the hospital to give him the good news. Even as he lay there in bed, he soon began conceiving ideas for a new automatic transmission. He was too anxious to wait until he could leave the hospital.

The new year arrived, and soon Hattori returned to the R&D Center with his AT concept in hand. It was 1965. In those days, several more-or-less practical AT specifications were available, based on different combinations of parts. The automatic transmission Hattori had in mind used a hydrodynamic torque converter and a transmission device. He came up with this combination because the torque converter was associated with good clutch performance and very smooth starting characteristics. Many U.S. models employed the system, and the general specifications were believed to be most appropriate.

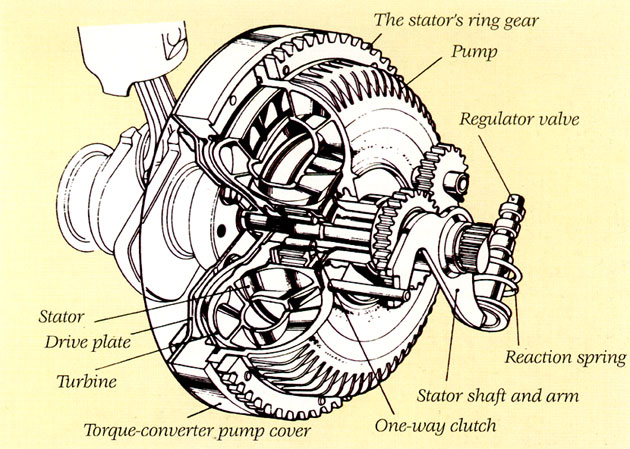

Perspective view of the torque converter. The stator’s reactive force is harnessed via the arm located on the right.

Honda, however, had no experience with hydrodynamic torque converters, though some previous models had used hydraulic mechanisms. Moreover, the development and commercial implementation of a new technology would require that all departments involved in the process - from development through production - have a degree of relevant engineering expertise. To develop an automatic transmission that could accommodate the characteristics of its models, Honda also needed to obtain data on actual vehicles. For these reasons the development team decided to start by building a prototype car. This, they believed, would help them discern the basic facts. As for the automatic transmission itself, they decided to ask BW to develop a prototype. This approach was a natural choice, since Honda possessed little of the technology. And in light of the aforementioned difficulties, the environment surrounding AT development did not promise a positive result.

Hattori quickly contacted BW with specifications he had drawn up based on the S500. Contrary to his expectations, however, BW replied that they would not be able to satisfy Honda’s requirements. Citing a displacement of only 500 cc, not to mention the required maximum engine speed of 8,000 rpm - twice that of a conventional engine - BW claimed they couldn’t find any AT specifications that accommodated those conditions.

Hattori’s dream was shattered. He had been planning all along to increase development efficiency by using an existing AT specification as the basis and refining the details to satisfy requirements. The unexpected reply from BW was a wake-up call for Hattori and his colleagues. He recalled the words of Soichiro Honda, then president of the company: "Success is the one percent supported by 99 percent failure." He realized that ultimately there was no other way than to give the concept a concrete form. They must correct the problems they find, test them again and make corrections, and repeat the process. There was no way anyone could get an excellent result at the very beginning. This was especially true, given the fact that automatic transmissions were known to be less efficient with engines displacing 1500 cc or less.

"We decided that if there was no automatic transmission we could use, we had to build one by ourselves," Hattori recalled. Yet, this unexpected turn of events rekindled the pride Hattori and his colleagues had as engineers. So, driven by the spirit of challenge, the development staff tasked with the creation of an AT began moving in a new direction.

Stator Reactive Force Brings Dramatic New Efficiency

The development plan had thus undergone a major overhaul. Instead of the intended prototype, the team purchased a BW35 mass-production AT unit from Borg Warner. The purpose here was to develop an original design based on the BW35 specifications. They also decided to use the L700, which was scheduled for market release that October, as the base vehicle for their prototype AT car. The L700 was already in the prototype stage, and test cars were available. Moreover, the model was a front-engine, rear-wheel-drive car, which would be an ideal test-bed for the new transmission.

Prototype development was now progressing, but the team was concerned about improving transmission efficiency. This, after all, was the key point in developing an automatic transmission. After days of trial and error, the team finally came up with the idea of using a stator’s reactive force to control hydraulic pressure.

The hydrodynamic torque converter consists of a pump, turbine and stator, and transmits engine power via oil circulation. The stator is used to convert torque, and is usually mounted in a stationary position. The development team’s idea was to make this stator free and movable. By using a bearing to turn the stator, they thought that sufficient force from the moving stator could be harnessed as amplified torque differential and transmitted to the hydraulic control valve. This could then engage the clutch based on the amount of torque present in the converter.

The control realized by this system was much simpler and more efficient compared to conventional hydraulic systems. This idea brought a dramatic degree of improvement in AT efficiency and was ultimately the basis for Honda’s patented technology on "an automatic transmission based on the detection of stator reactive force." It was an invention born through determination, a team effort and the desire to create something that didn’t simply copy existing technologies.

The prototype car thus completed, the development team quickly established a schedule for test drives in the area of Hakone. Attended by Mr. Honda and other board members, the test drive was held on a stretch of the Ashinoko Skyline scenic road around Hotel Kagetsuen. The car’s performance was well received by drivers and passengers alike, who were impressed by the absence of shock and vibration during gear changes, as well as its smooth shifting. Mr. Honda, who drove the car himself with executive vice president Takeo Fujisawa sitting in the passenger seat, was very pleased throughout the drive. "With this car," Honda said, "the driver only needs to hold the steering wheel. Even Fujisawa can drive it."

One surprising fact was discovered after the test drive, though. During the test drive, the car barely produced any shock during gear changes, a common characteristic of automatic transmissions. In fact, the car’s performance impressed even the development staff. However, it was later found that the clutch facing was severely worn, which was why there was no shock. The worn part was discovered the following day, during an informal test drive carried out by the development staff. That day, the worn clutch facing resulted in the very opposite of the impressive performance the car had demonstrated during its official test, causing various problems from pipe breakage to oil leaks and gradually an altogether inoperative clutch.

Based on the results, many improvements were added to the clutch facing, hydraulic control and a shock-absorption mechanism. Given the struggle and disappointment inherent in the process, the creation of a practical AT car - working from scratch - was nothing less than a major accomplishment. And with its initial success the development moved on to the next stage: to develop an AT model of the N360.

The Parallel-Axis System Derived from FF Design

The development of an AT N360 meant that Honda’s new automatic transmission, which was based on a front-engine/rear-wheel-drive specification, would have to be transferred to the front-engine, front-wheel-drive format (FF). Simple rearrangements in the layout could have been made relatively easily, but finding a space for the transmission in a small engine compartment turned out to be exceedingly challenging. There was, however, one way to solve the problem: they could integrate the engine and transmission within a single unit. Accordingly, the team went to work devising a "parallel-axis system."

A conventional automatic transmission employs planetary gears that are arranged along a single axis. The team’s parallel-axis version, by contrast, adopted a very simple and nearly equivalent structure that simply lacked planetary gears. This would allow the team to design a compact automatic transmission that produced less friction, a benefit that wasn’t possible with the conventional AT design.

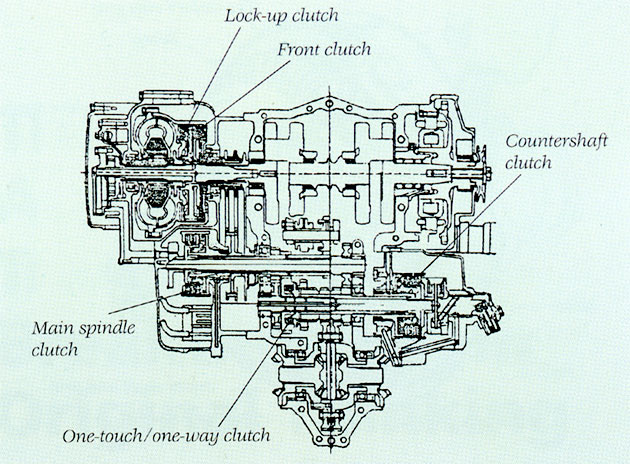

Numerous issues would have to be resolved, of course, before the new system’s performance could be brought up to the required level. For instance, in order to integrate the normally separate engine and transmission, those mechanisms were simplified to minimize the need for maintenance. Also, further improvements in efficiency were sought by testing a prototype AT with a lock-up function - a standard specification today - to ensure efficiency with the diminutive 360 cc engine. Of course, various cost-reduction measures were taken, since the N360 was intended to be highly affordable. In dealing with each problem, the development staff studied the design in minute detail, right down to bolts and valves. Through numerous failed attempts, they gradually identified ways of enhancing the system’s performance while reducing its size. On October 18, 1967, the N360 AT model with lock-up function was unveiled at the London Auto Show.

Overview of the AT system with lock-up function revealed at the London Auto Show in October 1967

The show having drawn to a close, Mr. Honda instructed the development team to add a manual selector mechanism so that the driver could choose between manual and automatic shift operation. Based on that directive, they incorporated yet another set of ideas in the development of a remote-controlled transmission with seven selectable gear positions: 1st, 2nd, 3rd, D, N, R and P. This and many other achievements were later refined and integrated into Honda’s proprietary AT technology.

The Hondamatic: Overcoming the Patent Hurdle

The Hondamatic transmission made its debut in March 1968 with the new N360 AT model. The car drew much attention as Honda’s original AT entry, especially since it was the first mini car equipped with a fully automatic transmission. In fact, the car’s glowing reviews gave the development staff the recognition they had long deserved: Ever since Borg Warner declined their request to develop a prototype, the staff had sailed a difficult and uncertain course, using trial and error as its waypoints.

Lurking behind the system’s sensational debut, however, were several journalists and automotive engineers who assumed that lawsuits would result from patent infringement. This decidedly pessimistic view also was shared by many who were knowledgeable about automatic transmissions.

Hattori was not exactly sure when the Hondamatic transmission made its official debut. And as a matter of course Honda had carried out exhaustive studies during development in order to avoid patent infringements. Personnel from the Patent Section frequently visited the Patent Information Center in Osaka, which housed the largest collection of patent documents relating to power transmission mechanisms. There they sifted through mountains of data, hoping to find patents pertaining to automatic transmissions. Even Hattori would make occasional trips to Osaka on weekends and holidays. Although everybody had done their best, no one could say for sure that they had checked all the files that had piled up on the shelves of the Patent Information Center.

Soichiro Honda was not about to run away from the issue, boldly claiming to the press that should a lawsuit be filed Honda was confident it would win. And though one can only speculate concerning his real intentions in making such a statement, those words are decidedly a reflection of Soichiro’s experience as an engineer, his resolute command as a business leader, and above all his faith in the pursuit of technology.

Mr. Honda discussed his views on the issue of patent infringement in an article entitled, "A Message to New Employees: Put Things in Right Perspective," published in the April 1966 issue of Honda Company Newsletter (No. 116). The Hondamatic transmission was, interestingly, still under development at that time:

"We [Honda] refuse to depend on anyone else. We will not copy foreign products nor pay royalties for the use of other companies’ patents. We don’t intend to get support from the government, either. I’m making it clear that we will do it our way."

It was this strong conviction that kept spirits high among the development staff at the Honda R&D Center, giving them the courage they’d need to overcome any major hurdle. Indeed, there were many outsiders who thought it would be impossible to achieve such a feat. In 1971, three years after the N360 AT’s debut, the company’s patent application regarding an automatic transmission utilizing stator reactive force was approved in Japan. The following year Honda won patent rights to the technology in Germany, and soon after was granted approvals in the U.S., U.K., France, and Italy. These patents gave Honda the power to enforce its claim. But more than that, they are a powerful manifestation of Honda’s commitment to proprietary technology.

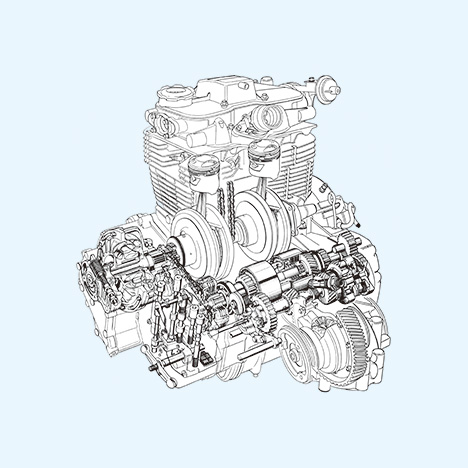

Illustration of N360 AT model’s transmission and engine, dubbed ‘Super Automatic’

The Courage to Try . . . Without Fear

The Hondamatic transmission was eventually adapted for use in Honda’s 1300 and Civic, and in 1982, the company led the industry in offering a four-speed FF AT system, this time with the Accord and Prelude models. This was in keeping with a shift in the general automotive trend from manual to automatic transmissions. The hydraulic control system and parallel-axis system - the Hondamatic’s two core mechanisms - remain very much alive today.

Several reasons contributed to Honda’s development of the trend-setting AT system, not to mention a major success in the area of patent ownership.

First, the development staff was not afraid of failure. Their courage to try new ideas led to the invention of the stator mechanism and innovative parallel-axis system. In an article entitled, "Engineers and Their Spirit," published in TOP TALKS in October 1978, Kiyoshi Kawashima, then president of Honda, talked about how the company had tackled the patent issue:

"It’s relatively easy to develop a technology based on an existing theory. However, we must possess the adventurous spirit needed to try out new ideas. We do this by giving them a concrete form, even when there is no existing theory to support them. We may not succeed right away, but we shouldn’t be afraid of that. Fearless experimentation often leads to surprising breakthroughs.

Secondly, Honda has always identified creativity as its key resource in product development. For example, Honda could simply have acquired existing patents rather than putting so much time and effort into developing the Hondamatic transmission. This would have been an easier course. Honda did not, however, view that as the best choice for a successful enterprise. To survive fierce market competition, Honda had to rely on own ideas and technologies, and see them through to the end.

It is not at all surprising that the personal motto of Hattori, who led the development of the Hondamatic transmission, is "if you imitate you will be criticized, but when you create you earn respect. "