Employing the "My Record"Project and

Expert Certification System / 1960

"Let's keep a record of your hard work!"

The April 1960 issue of Yamato Factory Bulletin magazine featured an article entitled, "Do You Have Great Skills That No One Knows About?" This article suggested that work-history notebooks should be created and distributed to all workplaces.

This work-history notebook was intended to be much like a diary. It was to allow each employee to share the hopes and passion invested in his or her hard work - and as well as the frustrations - with colleagues and supervisors alike. The notebook was to be kept at work for anyone to read, anytime. Its aim was to properly evaluate the individual's efforts and uncover any special skills that could be brought to the fore.

It was the planting of that seed which eventually became the My Record project implemented companywide the following July. In the August 1960 Yamato Factory Bulletin magazine, Senior Managing Director Takeo Fujisawa explained the purpose of My Record to all section managers of Saitama Factory:

"It's a good thing for every individual to keep a record of his efforts and the things to which he has devoted himself in his lifetime, whether it be in the form of achievements or the joys he has experienced during the process. It will be a record of memories when he leaves the company; perhaps a legacy to pass onto his sons.

"When you begin working on something new, you always agonize over how difficult it is. It requires a significant effort. As the years go by, someone else will take over and the work will function as a system. Eventually it becomes ordinary work, with nobody remembering who started it or how. That's the great thing about it. It's an achievement in and of itself. But keeping such facts on record to share and acknowledge with each other will enhance our sense of harmony in the workplace."

Creating New Rules through the My Record Project

Five or so employees joined Fujisawa in Tokyo's Happoen in May 1962, where they talked about the My Record project and shared excerpts from their notebooks. These young employees were chosen from various offices and factories. Ryuji Ito - then Saitama Factory's head of the Management Subsection, Maintenance Section - who a day earlier had been named to chair the discussion, suggested that everyone read a part of his record as a means of introduction. Fujisawa listened to each employee with keen interest.

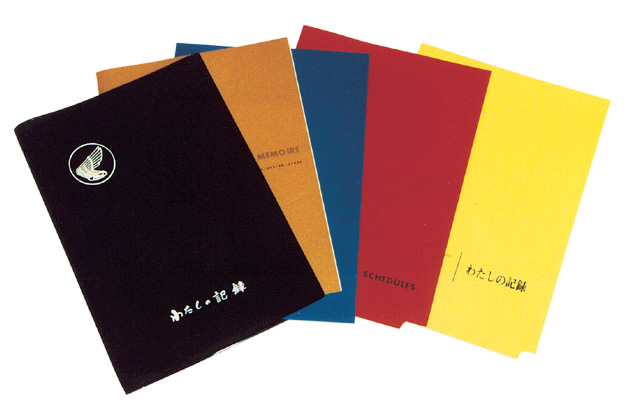

The first My Record notebook, when the project started, and successors showing various changes in design.

Fujisawa, delighted with how Ito had used his My Record notebook, signed his name on the page depicting the goals of My Record, as professed by Fujisawa.

Ito, using his notebook, related that in March 1961, during the production adjustment of Super Cubs, he had been inspired by a good-natured talk given by Fujisawa. Ito described how the employees came together to implement a plan of preventive maintenance for machinery and equipment during a five-day production-line break. He showed pages with graphs displaying production fluctuations and inventory movements. Pages were filled with key points for handling new equipment, as well as for preventative maintenance. There were pages of outline reports on the lectures and training seminars that he had attended.

Fujisawa was overjoyed, saying: "You have all done a great job. That was precisely my wish: to have people even on the frontline make plans and record their achievements, and to have more and more people draw up plans concerning their dreams. You are using My Record just as I had pictured it." Then he signed Ito's two My Record notebooks.

Newly imported machinery and equipment was in those days met with the concerted effort of young workers who, with manuals in hand, dedicated themselves to Soichiro Honda's challenge of using the machinery to its full potential. Accordingly, Ito had recorded the knowledge acquired through such experience in his My Record notebook. Moreover, he had expanded those ideas in the form of standard operating manuals and other useful materials.

"Mr. Fujisawa encouraged me, saying, 'Go ahead and establish new guidelines with what you have learned by keeping such records. This is something that can only be done while you have a youthful, inquiring mind.'" Recalled Ito, "For me, the My Record project represented the creation of new rules. It was a history of challenges I took up to create manuals and systemize operations."

Corporate and Personal Potentials

The opening of the Tokyo Olympics in October 1964 had captured the nation's attention. However, for a considerable time afterward-through the middle of the following year, in fact-the Japanese economy faced a situation known as the "Recession of 1965." While many other corporations struggled through a period of poor performance, though Honda was quick to enact measures to adjust production and promote the production of new models. These moves came in rapid succession, helping create new demand and ensuring favorable business performance. Additionally, with the Sayama Factory's auto plant opening in November 1964, the building of a foundation to advance as a carmaker was well under way.

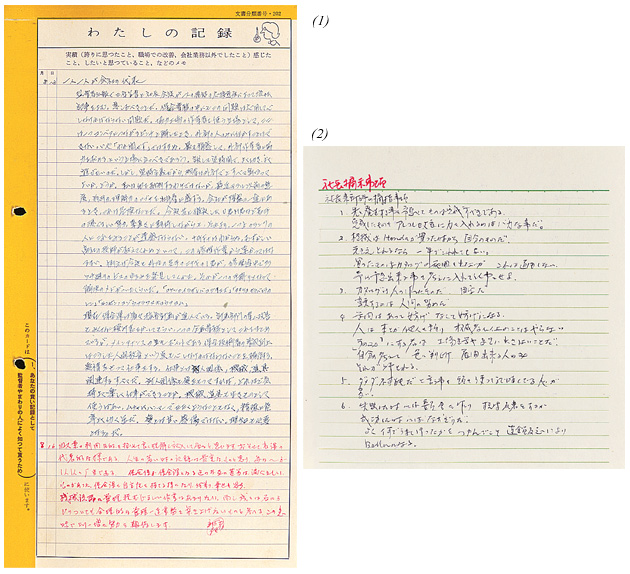

A My Record notebook

Examples of how the My Record notebook was used: (1) Courtesy of Ryuji Ito; (2) Courtesy of Yukio Tanabe

Financial statements for the 30th term (Sept. 1964 through Feb. 1965), however, showed a decrease in profits compared to the previous term, despite increased revenues. This meant just one thing: that increased production volume and continuing investment in new models might put the company at risk.

Fujisawa, despite such bottom-line issues, had expected the appropriate number of corporate employees to reach the 10,000 mark. Accordingly, he took this period of favorable performance with nearly 8,000 Honda employees as an opportunity to propose a new and original corporate structure. Fujisawa proposed the creation of corporate growth potential to ensure the future success of dedicated employees. Instead of depending on a conventional, pyramid structure, he saw that the company required a structure that fostered the potential of individual expertise.

Satoshi Okubo, then a manager in the Personnel Section, recalled that time. " 'Uncle Roppongi' [Fujisawa] often used the phrase, 'like a cloud.' What he meant was, he thought it would be a wonderful structure if it allowed the essential, talented workers to swiftly gather for work and return to their original positions when the job was completed, much the way clouds form and then dissipate. I thought that was the ideal concept for a system of experts."

A special issue of the Honda company newsletter published in August 1965 acknowledged the following problems:

1. The weakness of a large corporation is that it does not enable individuals to work to their full potential, but depends heavily upon a gigantic, pyramid structure.

2. We must first outgrow the present situation, in which we are struggling to fit into an outdated structure that was created when we neither produce nor sell a great volume of product.

3. When promotion is limited merely to supervisory positions, it can be excruciating for other talented people. We need to make clear that there is a way toward promotion as an expert, regardless of one is status or seniority. We need a structure in which talented individuals can continue functioning at maximum potential.

4. We need to clarify the means of compensation for employees who have reached a certain level of expertise. We need to create something that engenders in people a sense of hope and pride in their growing expertise.

Union Reluctant to Implement Certification

A special issue of the Honda newsletter published in October 1965 announced that the certification system was soon to be launched. In the newsletter, Fujisawa's concept of the ideal system for experts was referred to as the "3-D structure."

The Honda company newsletter, No. 114 (November 1965) featured articles on CRG activities and discussed the goal of developing experts within the company.

The structure was described as a mechanism that would allow Honda's leading experts to swiftly and enthusiastically work together where they were needed most, and when the company needed them. Thus, we would be able to resolve issues without a moment's delay."

It was also stated that Honda's idea of an expert certification system was unlike any other system in the industry. It wasn't simply a "stepping stone" path to becoming a supervisor, nor was it an empty encouragement or guarantee of status. The article noted that experts could only become motivating forces within the company when they were allowed to make use of their expertise. Pamphlets detailing the system of expert certification, it said, would be distributed at a later date.

However, the pamphlets were never distributed. This was because the labor union, despite acknowledging the necessity of such a certification system, was reluctant to prompt its implementation.

Seiichiro Suzuki, then chairman of the Honda Motor Labor Union, wrote in the October 1965 issue of the union newsletter, "The details of this system must be clear and reasonable. It must be operated fairly, with opportunities available to all members of our union."

Suzuki questioned the system's correlation of wages to work evaluations, asking that the certification standards be made clear to the union membership. Moreover, because the system was to be implemented in the technical area first, he maintained that adjustments were needed to ensure consistency of application in all areas. The company, he said, needed to avoid going ahead with the system in such a way that it may cause concern in the future.

It was finally decided that all details examined up to that point would go back to the drawing board for reexamination, including the input of all employees. The date of implementation was also postponed until a fully satisfactory proposal could be made.

Defining an "Internationally Accepted Expert"

Fujisawa, then the executive vice-president, in October 1965, made speeches at both Hamamatsu Factory and Suzuka Plant regarding expert certification and the ideal form the new corporate structure should have. Moreover, he outlined the purpose of independence for the R&D Center and his hopes for cultivating experts throughout the company.

He also defined the type of expertise that would be accepted in the global arena:

"Even if you are a titled member of management, you'd never know what will happen tomorrow. However, as long as you're confident in your own expertise, you'll have nothing to fear. In that case, I believe that competitors will attempt to recruit you. If Honda Motor were to produce a number of people so talented that our competitors would seek them out, the Honda philosophy would spread throughout Japan, making our country even more wonderful and productive. I truly wish you will take the opportunity to create a system that exists nowhere else; not in America, not in Germany, and certainly not in Japan."

In addition, at a discussion meeting of December 16, 1965, attended by Soichiro Honda and young employees from each factory, the company president shared his ideas about chiefs and experts on the production line:

"A chief or manager is only a title within a system," he said. "It doesn't actually indicate how great you are. Whether you are a section manager or not, if you are in charge of a machine and know how to control it, I will pay you a salary commensurate with your skills and treat you properly. A title should not represent who you are, but your work and your ability should represent what you are. If a person highly skilled at controlling machinery ends up spending all his time worrying about personnel issues, that will be a loss for both the company and himself."

That was how the two top executives, Honda and Fujisawa, described the importance of expertise. In those remarks they expressed their determination to realize the system of certification.

Finding and Nurturing Experts

The Certification System Promotion (CSP) Committee was established in August 1966. Earlier, in October 1965, the Cost Research Group (CRG) was launched. The CRG maintained records of its member's activities, and the CSP Committeeís job was to analyze those records.

The CRG represented a significant departure from what was traditional for the times. Its aim was to examine all types of parts and components used in manufacturing, and to achieve optimal cost reductions company-wide. For Honda, which had already made its entry into the auto industry, monthly expenses paid to parts manufacturers amounted to almost 7 billion yen. Therefore, the pursuit of cost-effectiveness was no longer applied just to the Materials Procurement Division. The entire company had become the subject of cost-reduction efforts, from different types of models to different types of parts. It was the experts working on the lines who played a major role in this activity.

To implement the certification system, the Certification System Promotion Committee presented the following three-step agenda:

1. Thoroughly record individual roles and achievements during various company operations.

2. Analyze the records and determine "the proper method for record keeping."

3. Devise "an evaluative method" using the consistent practice of recording and analysis.

Analysis was over the period of a year conducted on the activity details of 1,600 participating members working on about 350 CRG projects. The results revealed that many employees had been endeavoring to come up with ideas about how to perform tasks in addition to their specified jobs. Moreover, it was apparent that the secret behind such successful activities was valuable on-the-job lessons learned through repeated trial and error, and that ideas and proposals offered by participants often exceeded the bounds of their jobs or limits set by the system.

To get a valid picture of such efforts, it was decided that records would be kept and collected using My Record notebooks. Thus, each employee would be given a revised notebook with which to implement the new recording system. All activities and work including daily production-line work, group activities, meetings, assistance, and proposals-were to be recorded.

The role of the My Record notebooks first employed in 1960 had again come to the fore.

Individuals made entries in their notebooks, which were collected monthly by the record-system group. The details were then categorized, coded, and tabulated. There were six categories drawn from the results of the CRG's analysis: questions, ideas, concepts, materialization, guidance, and action. This system revealed how each individual's efforts and talents came to bear upon a certain area. It also was a significant step toward a system that could utilize the talents of every individual.

The Certification System Promotion Committee was reorganized as the Record System Committee in December 1966. Its purpose was to establish a system for the immediate and short-term registration of individual records, and to progress toward a definitive system of expert certification.

A special December 1966 issue of the Honda company newsletter, referring to the start of the record system, contained an article that stated, "Our competitors' certification systems employ an examination system or depend on set evaluations by production-line chiefs. Therefore, they tend to operate on an ideological, rigidly controlled basis. In contrast, we try to see beyond the established system and accepted job types to locate people on the job who want to become experts, based on their actual performance. Then we train them to become experts. I am confident beyond a doubt that this effort is unique to Honda."

Regarding the uniqueness of Honda's certification system, since it was based not on examination system but self-declaration and achievement, Okubo said:

"A term 'Uncle Roppongi' [Fujisawa] used was his 'masculine, human dignity.' What he meant was that men were verbally expressive and that self-expression was important. Uncle also said, 'We do not need experts who speak only in terms of concepts. Their achievements must demonstrate their skills.' I think this refers to the same thing that our Old Man (Soichiro Honda) referred to in the saying, 'Show off your talents, if you have them.' A talented person demonstrates his gifts when he uses them for a real purpose. They cannot be seen unless there are actual circumstances to support them. Therefore, even if we were to test that individual with a problem such as, 'When do you show your talent?' the answer would not be worth a cent. That is why our basic policy stresses achievements."

Compensation under Debate

Honda introduced the N360, a mini passenger car, in October 1966. Then, in December, it drew public attention as Honda announced a price of only 313,000 yen. When the N360 hit the market in March 1967, the response was phenomenal. Within three months, the N360 had topped Japan's list of registrations for mini cars.

Honda, determined not to miss the opportunity to establish a solid foundation as a carmaker, implemented a major, six-month increase in the production of N Series mini cars, starting in September.

A plan was devised that year to raise the average monthly salaries of employees by 5,000 yen through a combination of annual pay hikes in April and basic pay increases in September. At the time, this was Honda's greatest increase ever. Moreover, additional compensation based on ability was to be increased according to each individual's demonstrated level of achievement. The plan reflected Honda's future transition to extra compensation based on ability.

A special August 1967 issue of the company newsletter was entitled "Building a Tomorrow." It discussed the background of this major salary increase, as well as of the board members' hopes for Honda employees. The members also indicated their interest in compensating based on ability and achievements through proper evaluations of individuals. As a step toward identifying candidates for expert certification, it was proposed that a system of compensation based on recognition be established.

"At the time," Okubo said, "employees complained that the new record system was disappointing, because there were no rewards but only records and registrations. Therefore, we came up with an impetus to advance the record system a step further and enhance interest in the certification system. We likened it to the 'stairs (recognition compensation) between floors (levels)'."

The system was to work like this: Employees who were not quite ready for promotion to the next level but had shown that their efforts and achievements exceeded others at their current level could be recognized and compensated (at a planned rate of about 3,000 yen per month). Thus, the plan would result in compensation based on ability and achievement. However, negotiations were rough between the union and management regarding recognition compensation. The following is an excerpt from the 15-Year History of the Honda Labor Union.

"While we were working toward increasing wages, we in the union maintained that we couldn't accept a recognition-compensation system on face value alone. It was ridiculous to create a pump-priming measure for the certification system, in light of the fact that no certification system had yet been established."

Although it was agreed that the union and management would continue examining the concept of recognition compensation, it was not until May 1969, when additional compensation for experts was established, that specific amounts were exhibited and the system was implemented.

Expert Certification: A Dream Fourteen Years in the Making

On April 1, 1968, the Expert Certification System shifted into gear in the production and technical areas. Fifty-one technical chiefs from throughout the company were recognized and announced as Honda's first certified experts. They had received recognition based on accrued records and the passing of judgment by the Certification Examination Committee. Moreover, engineers and supervising engineers were recognized and announced as higher-level certified workers from among the technical advisers. Standards of recognition for each type of certification also were announced.

The roles of the Expert System and Management System (supervisors) were specified at the same time. An expert organizational chart, separate from the management's organizational chart, was also issued.

It should be noted here that an expert's duty was to "create the future." Recalled Shozo Tsuchida, certified as one of the first experts as the supervising engineer in the injection field, "Honestly, I felt a bit left out, knowing I would never be part of the management. At the same time, however, I felt responsible as the main pillar in support of Honda's working in injection technology. It was my duty to be ahead of others in the industry. I felt compelled to study it much more deeply."

Experts were recognized and certified based on individual ability, without regard for seniority. Accordingly, there was no limit to the number of experts. They were to be examined each year, whether or not they would be re-certified.

The expert organizational chart divided technologies into five groups: injection, surface processing, machine processing, quality/performance/assembly, and management assistance/design. The names of certified experts were included in the chart. For engineers and supervising engineers, the fields of their expertise were included, making it easier for their skills to be utilized.

"We had thought of the expert organizational chart as a picture of talents in stock," remarked Okubo. "We searched the categories in the expert organizational chart to see if we had the necessary people lined up. If we needed more, we could train them. The role of the expert organizational system was to make the company responsible for training, certifying and placing individuals. On the other hand, the role of the management organizational system was to utilize and evaluate people. The former was of an 'input' nature, while the latter was of an 'output' nature."

Engineers and supervising engineers were in May 1969 certified in other divisions such as Technical Management, Sales, and Accounting, in addition to the Technical Division. The level of directing engineer was also born as the highest degree of certification.

The perennial issue of salaries for experts was resolved on May 1, 1969, when salary regulations were partially revised. Extra compensation for experts was given to individuals at the engineer's level and up. Preferential measures for experts had at last been realized, even in terms of wages.

Fujisawa gave a speech at a July 1968 ceremony commemorating the founding of Honda R&D Co., Ltd., in which he expressed his feelings after having spent so many years creating a system that could bring the experts' abilities to the forefront of Honda's endeavors:

"It was you who determined how experts could be created from the My Record project," Fujisawa said. "Ultimately, I had no say in the matter, since you had created an organizational chart that was certain to result in prosperity for Honda Motor, thus bringing happiness to us all. It has taken fourteen long years to arrive at this point, from when I first hoped for such an organization. For fourteen years, all of us at Honda Motor have worked to create this organizational chart. I want you to take especially good care of it. I would be ever so grateful if you could continue making it grow, and mend any areas that may prove lacking in one respect or another."

The Expert Certification System and My Record Project

Major revisions were applied to the Expert Certification System in April 1976. Its structure was divided into technical and administrative areas, allowing the system to apply to anyone, regardless of his or her type of job.

Another significant change was to place a priority on certification, with roles assigned once an individual had been certified. Moreover, the certification period was extended to two years.

It became mandatory for experts to work on the front-line in manufacturing and sales for one month each year. Additionally, in order to obtain broader experience, they were asked to experience tasks that, in the case of production work, came before and after their normal line of jobs. Subcommittees for each type of job also were established in order to enhance the training system by which workers could become experts.

Management certifications were reexamined and skill certifications were established in October 1994. Also reexamined were the on-the-job training program and the standards and conditions of recognition for certification.

These two major revisions occurred amid a world of dramatic change; a world in hot pursuit of the expertise Honda had demanded. However, there remain certain problems in the system. Because the expert job categories closely reflect daily work, certification tends to be perceived as an expected benefit in the line of one's work.Therefore, the training functions of subcommittees have been weakened. Issues such as these need to be resolved in order to ensure progress.

The My Record notebooks that became the basis of the system are rarely used the way they used to be. Many employees use them merely to record memos.

Notebooks are alive and well in Suzuka Factory's Synthetic Resins Section, however. In fact, they are the basis for accumulating records used in the certification system.

"I cut out and paste drawings from the improvement suggestion forms that have been returned to me," said Takenori Ao of the section, who organizes improvement suggestions in his own notebook. "Then I surround the drawing with questions and ideas for improvement. These are then categorized into questions, ideas and concepts to be recorded on a cumulative chart. When I discover comments written by our group leader in my notebook, it gives me great joy to know that my work has been acknowledged."

Said Takeshi Yamamoto, Ao's former group leader, "For generations we in the Synthetic Resins Section have followed the tradition of using My Record notebooks. Things that are written in notebooks are useful not just for accumulating records for certification. The remarks are also useful in training new, talented workers. This way we use them as discussion materials concerning improvements to be made at work locations and revising the charts of operating standards."

The My Record project lives on today, just as Fujisawa had hoped.