Neighborhood Workshops and Super Factories always have

"Dreams and Youthfulness" / 1959

In January 1959, Honda dropped in by himself at the Yamato Plant and called out Takao Shirai, the head of the Production Engineering Division. Shirai had just resolved an early problem arising with the Super Cub at the end of the previous November, and he had just finished setting up for expanded production at the end of the year.

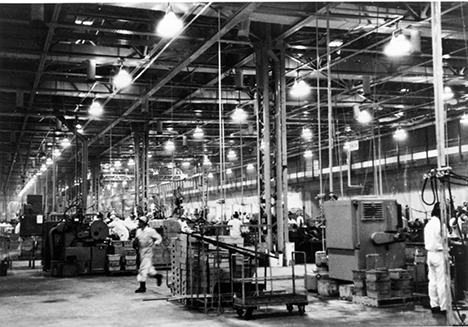

Thirteen years after that crude, barrack-like Yamashita Plant, Honda completed its Suzuka Factory with the mass-production capabilities they had dreamed of. This was the most advanced plant of the time, and visitors streamed in not only from the motor vehicle industry but from other industrial sectors as well, to observe it in operation.

He remembers the occasion:

"I could hardly forget it. It was in the evening of January 19. All of a sudden, I was told, 'You're going to Europe for a while.' I asked what for, and was told, 'Just go. You can figure out a purpose on your own. You also can decide how long you want to stay over there.' That was all he told me, without a word of explanation.

"The Super Cub was selling and selling. However, that was during the period that people called 'the pan-bottom economy' because of the deflationary recession going on. Foreign currency reserves were low, so it was difficult to get both a travel permit and a foreign currency allowance. Later in the same year, Mr. Kiyoshi Kawashima made our first entry in the TT Races, and Mr. Kihachiro Kawashima established American Honda, so there was a lot going on. In any event, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry turned me away twice. They looked at my resume and flatly refused, saying, 'Why should someone with a degree in economics who is neither a salesman nor an engineer get to use our country's precious foreign reserves to go overseas for no particular purpose?' The third time around, I told them, 'Honda is certain to be earning foreign currencies in the near future; we are now making motorcycles that can be exported to the world, and if it doesn't work, I'll kill myself.' After this most unconventional approach, they finally gave permission, but only for travel. Mr. Kihachiro Kawashima sold plenty of Super Cubs in America, so I didn't have to commit suicide," he said, laughing.

Without a single dollar of foreign currency, but only a round-trip air ticket, Shirai set off to Europe. For his expenses in Europe, Honda had requested a trading company there that was importing machine tools to advance him funds. Shirai recalled:

"Anyway, my work was production engineering, but I wanted to be able to answer any questions that might come up when I returned, so I went all over and listened to everyone and looked at everything, including plant facilities, of course, and personnel management, pay systems, traffic conditions, parking practices, fashions, everything. I did this in Germany, Switzerland, Italy, and England. Germany was the most advanced in manufacturing plants, so I went back there again. A while later, on June 20, a letter came to me from one of my colleagues at the Yamato Plant, Mr. Enomoto.

He wrote, "Actually, there's a plan to build a new Super Cub plant. They've selected several prospective locations, and are waiting for you to come back. 'The Honda Way’ has alleged that I had been told about the project before going to Europe, but in fact, I really hadn't been told anything about it."

After being away for three months, Shirai hurried back to Japan. This was because he knew very well that once a project had been decided on, Honda would move with lightning speed, no matter what, to set it in motion. Shirai remembers:

"Just as I had thought, the president had been waiting for me to show up. 'Starting tomorrow, I'm going to go look at the prospective sites. You come with me.' The president drove his own car, and the passengers were Managing Director Kensuke Takahashi, myself, and Mr. Shiozaki. We set off to tour the locations."

The major candidate sites were two locations at Takasaki in Gumma Prefecture, Utsunomiya in Tochigi Prefecture, Inuyama in Gifu Prefecture, and two locations at Suzuka in Mie Prefecture. Shiozaki recalls how he actually got left behind during one trip to a potential site:

"The Old Man's criteria for site selection included more than just building conditions and inducements. 'Before land and water and electricity, see, it's people. We'll choose the people who live in the location.' This is a direct expression of the Old Man's idea of the value of the human being. His idea was that no matter how good the other conditions might be, what came first was a place that had sincere, honest people. This includes the people in the local government. At one prospective site, a long line of cars belonging to prefectural assemblymen or something followed along right behind us. On finishing a presentation about the site, somebody from City Hall said that we would move on to hold the rest of the discussion at a restaurant where they had made reservations. The Old Man said, 'I'm leaving!' and jumped in his car and drove away," said Shiozaki, laughing.

"Mr. Shirai and I ended up taking the train back. The Old Man was still angry the next day and said, 'I didn't go there to get treated to a fancy meal!'

Their experience at Suzuka was in complete contrast, as Shiozaki recalls:

"At Suzuka, everything surprised me from my first impression forward. First of all, the City Hall was different. Government offices wherever you go have desks piled high with papers, or at least that was our preconception. However, at Suzuka City Hall, everything was neat and orderly without a thing out of place. When we went into the reception room, someone quickly brought us oshibori hand towels. They brought us those and chilled green tea. It was not hot tea. This was in July, at the height of the summer heat. Then there was the Mayor, Ryuzo Sugimoto, who was waiting for us wearing not a suit but work clothes, and he had on gaiters."

The Honda party was quickly taken to see the site. Shiozaki further remembered:

"Mayor Sugimoto made a quick signal. At that moment, a line of flags rose up all at once in the distance. 'From there to there is the candidate property,' he said. We could see the whole thing at a glance. I said to myself, they're pretty good. I was impressed. That moment is still vivid in my memory even now."

Mayor Sugimoto also explained the inducement conditions himself. According to Shirai:

"It was beautifully done, that's all I can say. We were scheduled to visit another strong candidate site on the next day, so for my part, I didn't feel that I could say anything hinting at a decision. However, when we returned from the site to City Hall, we again were given oshibori towels and green tea, but not a single tea cake was to be seen. They must have just served what they had, without getting in anything special for us. This was the kind of mayor they had running the city government. I thought, if we come here, we'll be all right, no doubt about it. That much I felt sure of."

The prospective sites were studied thoroughly and quickly.

"I examined the two Suzuka locations, sites A and B," said Shirai. "I compared them with the other prospective sites, and reached my own conclusions. Returning to Tokyo, I spoke to Mr. Honda, Mr. Fujisawa, and the other board members in a meeting. I told them that I thought site B at Suzuka was the best. Site A was 400 m wide from north to south, and 1500 m long from east to west. A long, narrow property like that is not suited to a manufacturing plant. Considering future expansion, I said, site B is the best. Mr. Honda said, 'I think so, too,' and Mr. Fujisawa said, 'Then let's settle on that site.' With that, the location of the present Suzuka Factory was decided."

However, the board meeting then proceeded to developments that Shirai had not expected:

"Mr. Fujisawa went, after that, to say: 'The new plant in Suzuka will be of a kind never seen before anywhere in the world, and we're going to put young Shirai in charge of building it.' I thought, what? After all, I knew very well that this was a major project that might determine the company's fate. I had learned something in Europe, and I had been expecting to participate in this project, but I had never once considered that I might be given that responsibility. Then Mr. Fujisawa went on: 'Considering the magnitude of this job, I want all of our operations to agree unconditionally to any personnel requests that Shirai might make. ' Mr. Fujisawa asked every one of the board members for his reply. They had no choice. 'Good,' he said, 'everyone concurs, so you can set your mind at ease and go to work.'"

Shirai can still remember the tension he felt then as though it happened yesterday:

"Then, Mr. Fujisawa looked at me and said in a very loud voice, 'However, there are two conditions. One is that you use as much money for this as you want. The other is that the money you use must be recouped within two years. There are no other conditions at all. Apart from these, you do as you like.' The president nodded in agreement and looked straight at me."

Shirai was 39 years old at that time. Naturally he was not a member of the board, but a plain section head. Here, again, the company was choosing a youthful contender.

In June, Honda underwent its eighth capital expansion. Its capitalization was now 1,440 million yen.

It is not known how early Honda and Fujisawa had been talking over this new plant construction project. It is certain that the project was already in motion when Honda ordered Shirai to go to Europe. The products made by Honda were on the verge of becoming acceptable around the world. What was needed next was a production plant capable of producing them in large quantities.

Honda's previous investment in imported machine tools had been a major gamble, but this new plant construction project was an even greater undertaking, and the company's future was on the line.

"The board officially presented me with three basic requirements," Shirai recalled. "The first was 'that this be a mass production plant utilizing rational methods of a kind that have never been realized before.' The second was 'that no limit is set on the amount of money to be invested, but the investment must be recouped within two years.' The third requirement was 'that the plant be harmoniously integrated into the local community.' The second condition that Mr. Fujisawa laid out to me during the board meeting was the pure expression of his approach to plant operation grounded in his unique business experience. The first and third conditions for my taking on the plant were likewise the pure expressions of Mr. Honda's ideals and philosophy. So, you see, the various conditions clearly express the personalities of these two men. Mr. Fujisawa very firmly put a lid on any further discussion by the members of the board, and so made it possible to set conditions that would allow me to do everything I would need to do. At first I felt stiff all over, but then I settled down with the strong sense of determination that I would repay their confidence in me."

Toward the end of July, a Suzuka Construction Project Office was established. The four members who first gathered at the office in the Saitama Factory were Takao Shirai, Sadao Shiozaki, Kotohito Takahashi, and Tsuneko Oshima. They set up a liaison office in the Kanbe area of Suzuka City to serve as a local base.

They moved into action immediately. The first order of business was to apply for permission to convert agricultural land to industrial use. Shirai recollects:

"Japan during that period was still trying to expand agricultural production, so the kind of reduction in agricultural use of land we see today was unthinkable. The primary purpose for land was agriculture, so we knew that the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry would not easily approve our application. Ten years earlier, soon after I joined Honda, I had worked very long and earnestly on the report to go with the company's application to the Ministry of International Trade and Industry for a subsidy. Since then, however, I had grown rather shameless. This time, I decided to put on a flamboyant show of what we had. Nothing concrete had even been decided yet, and we didn't know just what kind of plant it was going to be, but I went ahead and wrote the application as if we did. So I gave them a pretty big show, about 33,000 m2 in size," he added, laughing. "I made it so that the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry would understand that Honda was using the large parcel of land for this kind of purpose, and accept that the application was valid. I took that over to the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry and to the Ministry of International Trade and Industry, and the application was approved."

The next order of business was to get down to concrete work on the actual project itself. Shirai remembered:

"We were deadly serious about this. I would have to decide on the basic layout myself. For this, I had to think carefully about many different issues in combination, including how the plant should first start operating and what stages of expansion should be planned for at how many years in the future. With a view to future expansion, I would need to ask the city whether a junior high school located on the property slated for later acquisition could be rebuilt on a nearby hill at Honda's expense. I went to talk with Mayor Sugimoto, explaining our desire to expand the plant later, and obtained his definite approval. We grew even more intensely busy."

Decisions were made to have the Kintetsu train line extended to Hirata-cho, and to purchase property for water supply facilities.

Meanwhile, it was also necessary to make plans to satisfy Fujisawa's condition that "the investment will be recouped within two years." Shirai says:

"The period was two years, but we could never make that time limit if we waited until the plant was completed. What we could get started moving most quickly was an engine assembly line. Our idea was to set up a temporary plant at the parts receiving center and bring that on line in April 1960. Our production plan called for finished vehicles to start coming off the line in the main plant from August."

Shirai's team had to move quickly to realize the dream-like vision of "a mass production plant utilizing rational methods of a kind that have never been realized before." Shirai went on:

"We made this plan on the basis of a reverse concept starting with recouping of the investment. After all, this was our greatest concern. It seemed unlikely that we could manage to recoup the investment within two years by running just two shifts. If we were dealing with three shifts, then it would be better to build a windowless, totally air-conditioned plant so that weather conditions, differences between night and day, and differences in temperature would not affect our employees. The notion of plant construction commonly accepted in Japan at that time, meaning a steel-frame structure with a slate roof, would not work for us. We needed a ferroconcrete steel-beam structure. Construction costs would be higher, but we were aiming for a plant that could function ten and twenty years into the future. So we went ahead. I reached the conclusion that we would not work from the usual Japanese sense of scale."

Then there was one more major issue, "that the plant be harmoniously integrated into the local community." Shirai further reminisces:

"A plant that is not bound to the local community is not a plant for the future. We thought about the people who would be coming to tour the plant, and decided to build an observation corridor on the second floor. However, Mr. Honda's idea of harmonious integration with the community meant much more than that. Ever since the Shirako Plant was built, he had been very fastidious about not allowing Honda plants to disturb the surrounding community. As we would put it today, a plant should harmonize with the area and with the local environment. However, Mr. Honda's ideas on this were more than just a facade. He truly believed that we have to get along well with our neighbors. The question was, how to make this happen at the Suzuka Factory. This was another major assignment for us."

Shiozaki had himself experienced Honda's care and concern for the local community on various occasions. As he recalls:

"An eel restaurant proprietor who lived near the Shirako Plant came to us and complained that the engine durability tests made so much noise that he couldn't sleep. The engines were running 24 hours a day, so it was no wonder that someone complained. Then one day the Old Man heard about it, and he said, 'I want you to be working, but I don't want it in such a way as to trouble our neighbors. Do something about it!' So we said, please stop the engines so we can do sound-proofing work, and, 'Idiot!' he said, 'If it was just a matter of turning off the engines, I wouldn't ask you! ' So then there was nothing else we could do. We built another large structure right on top of the building containing the engine testing laboratory, to cover it," said Shiozaki, laughing. "We stuffed fiberglass into the space between the two structures. While we were doing this, all we heard from him was, 'Do it soon. Do it fast. Do it today.'"

The employees were also encouraged to submit ideas for the new plant. Many suggestions from the shop floor were incorporated into the designs.

Shirai gathered a carefully selected group of employees in the Suzuka Construction Project Office. At the core of the management section was Masami Suzuki. The cost that Fujisawa had specified for the Super Cub to be built at Suzuka was about 20% lower than the Saitama Factory's production cost. The total construction cost at Suzuka, including company housing, dormitories, and so on, would require 4,500 million yen.

"I had Mr. Suzuki thoroughly calculate our cost projections," Shirai recalled. "The bottom line was that we would have to produce 60,000 units a month. Two years would still be nearly impossible, but I judged that we could recover the investment in two years and four months. This would extend four months past the deadline set by Mr. Fujisawa, but I concluded that expenses should not be reduced for that reason alone."

In September, construction work began at a rapid pace. On the 26th of that month, however, that area of Japan was assaulted by Typhoon Ise Bay, which was said to have been the most powerful in the history of meteorological measurement. Shirai remembers:

"The first report came in from Mr. Shiozaki. The gravel that was especially vital for foundation work had all been taken to repair flooding damage, and they couldn't get any more. I replied that delay was unacceptable, and construction could proceed if they could obtain 70% of the total amount required. Then Mr. Shiozaki managed by extremely hard work, which hardly allowed him any sleep at night, to obtain gravel from the Yasu River in Shiga Prefecture and from as far away as Kyoto. Despite the occurrence of a problem of this magnitude, the project schedule was not delayed. This was thanks to the people on the spot."

Shiozaki implemented thoroughly unconventional ideas in order to speed up the work. Shiozaki recollects:

"The construction company's architectural blueprints for the plant were delayed. If they were going to be one month late, we would either have to pour concrete now or face another month's delay. So they drew up just the blueprints of the foundation for us. We decided on a column interval of nine meters and proceeded rapidly with the work. About the time that the concrete had dried, the building blueprints were ready, so we were able to go ahead and start the construction work. This is the kind of idea you come up with when you follow the Old Man's way of thinking. You won't find it coming out of someone who thinks conventionally," he laughed.

A number of suggestions and ideas for the project had been collected from Honda's various workplaces. Shiozaki worked these into the foundation laying that had already begun and created a layout drawing for the 36,300 m2 plant. He then turned that into a three-dimensional rendering from an aerial perspective that would allow the entire layout to be grasped readily.

In January 1960, the building blueprints and layout were completed. They depicted a windowless, fully air-conditioned plant of an advanced kind never before seen in Japan's motor vehicle industry or any other industry. Shirai says:

"Before we started on the layout, Mr. Fujisawa told us, 'I expect you to make this a plant exclusively for Super Cubs.' I replied that no, we were thinking of automobile production in the future. When he heard that, Mr. Fujisawa got very angry. He said, 'I've never considered having anything whatever to do with four-wheeled vehicles. Just confine your thinking to the Super Cub.' I could understand that, too. However, I had been working together with Mr. Honda continuously ever since the Hamamatsu days, and the cherished hope of his life covered more than just motorcycles. I was sure that his dream extended to automobile manufacturing. I wanted to realize Mr. Honda's dream for him on this site and in this plant. No matter what Mr. Fujisawa said, this was one thing I intended to accomplish."

As it turned out, he did not deviate from his professed aim.

Nor did Fujisawa issue further orders for him to stop.

The Suzuka Factory was designed to be an optimal mass-production facility for the Super Cub. However, it was from the very first given the flexibility to make automobile production possible there, if the time came for that.

Honda looked at the layout and listened to the detailed explanations by Shirai and other members of his team. The die casting plant had been located with consideration for the people living in the area, and so, had even included research on prevailing summer and winter winds. The company housing and dormitories were not placed all together, but were dispersed throughout the community. No cooperative store just for company employees would be built. Apart from a clinic in the plant, employees needing medical care would be directed to local hospitals. And, beyond these and other, similar measures, the plant did not have a wall surrounding it to separate it from the outside world. Instead of a wall, trees and greenery would be planted.

This plant held resolutely to the concern for harmonious integration with the community that Honda had wanted to see.

The Suzuka Factory entered into operation in April 1960. As Shirai had forecast, the initial activity was engine assembly. The Super Cub C102 with a self-starter also appeared in April, and the bike's popularity grew yet greater. Its sister bike, the Sports Cub C110, made its debut in November.

In May, Honda underwent its ninth capital expansion. Its capitalization was now 4,320 million yen.

In July, Honda's R&D Center was given an autonomous status to become Honda R&D Co., Ltd.

In December, the company launched the CB72 Super Sports bike (a sister to the C72 put on sale in February). This motorcycle would go on to define the new category of sports bikes in Japan.

Super Cub production grew rapidly, passing the one million unit mark as early as June 1961. In August of that year, production of all Super Cub models was transferred from Saitama to the Suzuka Factory, which continued in operation at full capacity as a mass production plant on a hitherto unprecedented scale.

Honda had taken its first step toward mass production at the Yamashita Plant, just 330 m2 in area, in 1948. Now, thirteen years later, the full reality of its cherished idea had been achieved.

During those years, the company had consistently held to a course of self-determination and independence. Now, looking back at that period of time, it was revealed as an unending series of challenges. For that reason, it had been an era of dramatic change filled with repeated failures and successes. Nevertheless, the dreams embraced by Soichiro Honda and Takeo Fujisawa were brought to fruition by young people who pursued the same dreams with them.

However, Honda had not reached its final goal. Its unfulfilled dreams are to unfold boundlessly.

The generation of those who lived through the events of that period join their voices in unison, saying:

"The young people of today will probably not have the same experiences that we did. Although the times may change, the basic Honda philosophy holds true. As we did in the past, the people of Honda today and in the future inherit it and pass it on to the ensuing generations. So long as this continues, Honda will not be just a major corporation. It will always go on being Honda. After all, youthfulness and dreams exist in every age."