The Appearance of a Full-fledged Motorcycle,

the Dream D-Type / 1949

The cumulative total of the motorcycles produced by Honda passed the hundred million mark in October 1997. This is counting from the very first motorcycle Honda made, the D-Type which debuted in August 1949. It was named the Dream, a name that seemed to symbolize Honda itself, and this machine was the embodiment of the company’s dream of becoming a motorcycle manufacturer. It is no longer known who gave the D-Type this name.

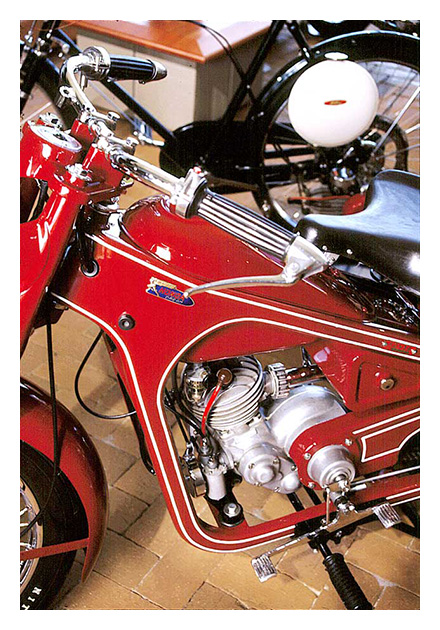

The revolutionary feature of the Dream D-Type was that "it did away with the hand-operated clutch." The lever on the left looks like the clutch at first, but it is actually the front brake lever.

Years later, President Honda said, "I can’t remember. I was always talking about how Honda would become a world-class manufacturer, which was like a dream. So somebody probably just started calling it that."

"I think the Old Man was really happy about it. After all, it was a real motorcycle," said Kawashima, who was in charge of drafting engineering drawings for the D-Type engine, as well.

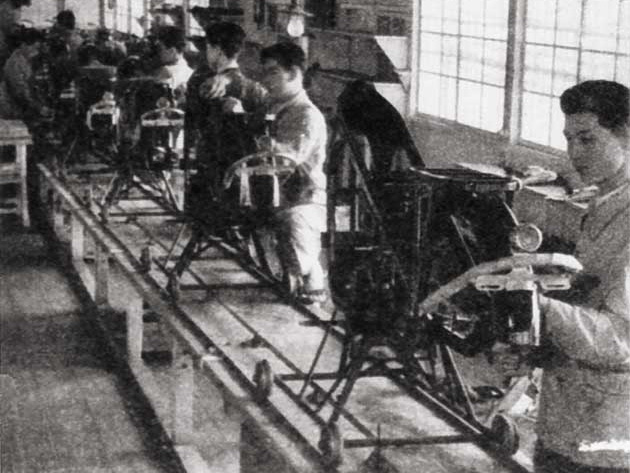

The D-Type was an offshoot of the C-Type, but it no longer had the look of a bike with an auxiliary engine. The design had evolved into something appropriate for a motorcycle. The D-Type assembly line also used a powered belt conveyor. This was an original company design.

"The line was on a slope, and the assembly process moved from the higher end to the lower end," Isobe recalls. "This was the way to make things easier for the people working the line in terms of their posture. When you pressed a switch, a bell would ring and the line would move forward one step in the process."

The company was starting to be more aggressive in taking up the challenge of mass production. "But, as I mentioned before, the precision of the parts was far from what it needed to be, so we still had to hand-work them to get them right, and the conveyor line had to be stopped all the time. It was thanks to this challenge and this experience, though, that everyone fully absorbed the fundamental idea that the parts handed to the line should not need any further working."

The conveyor belt mass-production process for the D-Type at the Noguchi and Tokyo Plants was the subject of an article in the December 1956 issue of Science Asahi (Kagaku Asahi) magazine. The article said: "There is a company that has achieved a production increase unthinkable in our time, producing 876 units in fiscal 1950 out of the national production total of 3,439, and then leaping to 700 units a month in fiscal 1951. As the reality of free trade approaches, the first thing people talk about is the cost problem. But costs are difficult to cut in any sector, and the greater difficulties faced by larger companies are well known. It is not easy to streamline a business without taking some kind of special measures. This is what the Honda Motor Co. has been exploring in actual practice. With a mere 150 employees, they have been using die casting methods not found even in European motorcycle engineering, and manufacturing all their own engines. Perhaps the key to increased unit production is to be found in this direction."

At that time, all the other motorcycles manufactured in Japan used steel tube frames. Among them, only the Dream D-Type used a channel frame made of pressed steel plate. Furthermore, at a time when the market assumed that motorcycles would be painted black, Honda gave its product a beautiful maroon color to the President’s taste. The D-Type stood out on the road, and the Honda name took on tremendous appeal. Sales were good from the very start.

"We used a channel frame of pressed steel plate partly because it was so difficult to obtain good quality steel pipe," said Kawashima. "What the Old Man was aiming for, though, was increased production speed and streamlining of the production processes. The Old Man was constantly talking up the switch to press fabrication and to die casting. This was a manufacturing method based firmly on conviction. Compared to steel pipe, the work required for fabrication was completely different, and we could keep the quality consistent. This method also required welding at fewer points.

"However, the idea for that type of frame wasn’t original," he added. "Various manufacturers in Germany and other parts of Europe had been using it since the 1920s, and in Japan, too, a prewar company called Miyata had used the same method. The Old Man hated to copy other people, but in the early days, we often used precursor machines for reference anyway. However, we never made a complete imitation, no matter what. That’s why the D-Type is filled with new ideas that are typical of the Old Man’s thinking. These are ideas that you could say were revolutionary. However, that’s also part of the reason that sales dropped off after doing so well at first."

The new machine seemed to have gotten off to such a fine start. Why, then, did it stop selling?

In 1949, when the D-Type was put on the market, the U.S. government and the General Headquarters of the Allied occupation forces issued orders for anti-inflationary measures. The Japanese government was forced to implement deflationary policies that year. All of a sudden, a recessionary storm began to ravage the economy. The business recession was not the only reason for sluggish sales. From around this time, the motorcycle market was shifting, and people were turning away from the 2-stroke engine with its high-pitched exhaust sound and selecting instead the quieter 4-stroke machines with deeper sounds. In addition to that, the D-Type’s unique mechanism was having the reverse effect of hampering sales.

"I think that the Old Man wanted to make a motorcycle that was different from the ones before," speculated Kawashima. "The part of riding a motorcycle that needs the most technique is working the clutch, just as with a car that has a manual transmission. If you don’t engage the clutch just right, the engine might stall or the bike might lurch forward. In any case, it’s hard for a beginner. That’s why he wanted to eliminate this problem. One of his points was to make it so anybody could ride a motorcycle easily, without having a particular ability or needing to develop the knack for it.

"On a proper motorcycle, and this is still the case today, the clutch is engaged manually. It’s mounted on the left handlebar and you operate it by squeezing the lever just the right amount by hand. Once you’re used to it, there’s nothing to it, but I think that in the Old Man’s view, this kept it from appealing to everybody."

In other words, the Dream D-Type was a revolutionary motorcycle aimed at eliminating the manual clutch operations that required rider familiarity. Thus, it constituted a bold challenge to the accepted notion of the motorcycle at that time.

Motorcycles ordinarily have the clutch lever on the left handle bar, but on the Honda machine the lever on the left was for the front wheel brake instead. The short lever on the right-hand side was a decompression lever used to make kick-starting the engine easier, or to stop the engine. In other words, there was no clutch lever.

That is why operating the clutch on the D-Type was so easy. Pressing down and forward on the change pedal with the front of the foot would put it in first gear. Letting go would return it to neutral, and pressing down and back on the pedal with the heel would put it in second gear. This was the first motorcycle in Japan to have a semi-automatic clutch system with a cone clutch mechanism.

Smiling wryly, Mr. Kawashima recalls: "It was extremely popular at first as a very easy-to-ride motorcycle. But then, after a while, people started to complain. The D-Type had two gears, low and high. The way it was made, though, in order to keep going in first gear, you had to keep your foot pressing down on the change pedal. If you were going up a long uphill road, for example, your toes would get tired from keeping the pedal pressed down. It was good not to have a clutch, they said, but this was no good. That was why the sales suddenly dropped. We just got too far ahead of ourselves with the idea of what would be good for the customer, so I guess this was another failure. Coming on top of the economic slowdown, this was real trouble. It was the Honda company’s first business crisis."

The challenge of making "a motorcycle anybody would find easy to ride" resulted in something far from success. They had not begun the project expecting it to fail. It was just that their engineering had not yet matured to the level where it could satisfy their customers.

"Even with that, the Old Man was full of fighting energy. He never let us see him look discouraged," Kawashima recalls. "He’d say, ‘There are any number of failures in life. If you do something you think is right and you have a flop, it’s not a wasted effort. Just finding out that you’re on the wrong track is getting a lucky break.’"

In August of that year when the Dream D-Type went on sale, the swimming champion Hironoshin Furuhashi went over to America and set a fantastic new world record in the 1500 m event at the All-American Swimming Championships. He left the second-place swimmer almost two whole laps behind. The radio had a late-night live broadcast, which was very rare, and the newspapers put out extra editions despite paper shortages. The whole country was excited at the news. Hamamatsu in particular was going wild, because that’s where Furuhashi was from. "Looking back now, I think that’s when the Old Man started talking about being ‘Number One in the world,’" said Mr. Kawashima.

As Mr. Kawashima remembers it, he had never heard the President use the words "the world" before.

"‘We Japanese lost the war to America and lost all our self-confidence. But Konoshin Furuhashi (his name was actually Hironoshin, but this is how President Honda called him) started from nothing and stuck it out. Furuhashi is an Enshu area person, and I’m an Enshu person, too, so no way I’m going to give up!’ That was his attitude. To me, he said, ‘Kawashima, you were one year ahead of Furushashi in junior high school, weren’t you? So get it together!’," recalled Kawashima, laughing. "Over time, the things he said to me grew more and more harsh. He got to saying, ‘Working on ‘pon-pon’ here in Hamamatsu is a dead end, we have to go to Tokyo.’ And then finally it was that famous statement of his, ‘If we aren’t Number One in the world, we won’t be Number One in Japan.’ That was the way his thinking just leaped ahead, and I was half impressed by the Old Man and half shocked by him," said Kawashima, laughing again. "He would have a goal so enormous it seemed like a dream, and he’d just blurt it out. Then, once he’d come out and said it, eventually he would be certain to achieve it. That was the Old Man. But it was a long time before I came to understand that about him."

Still, in 1949, when Honda was facing a crisis, the company was moving to become a full-fledged motorcycle manufacturer. Its products and its production system were based on innovative concepts never seen before in Japan, and with these Honda was taking up its new challenge.

However, there was something missing in the Honda Motor Co., and that was a sales system and a business strategy. In these respects, it was still the same old company it had been before. Then, just at this time, President Honda had an encounter with Takeo Fujisawa, which was to determine the fate of both men.

A look at the course of events that brought Soichiro Honda and Takeo Fujisawa together provides a clear picture of how these two individuals who built up the foundation of the Honda Motor Co. had each formed his own distinctive character, way of thought, and philosophy.